Since the first centuries of Christianity, Mary and the saints have played an important role in Catholic belief and practice. In the first four centuries of the Church, devotion to Mary developed into a central marker of Christian life. In the same era, martyrs of the early Church began to be held up both as exemplars of faith and as intercessors.1

The relative importance of Mary and the saints in Catholics' religious imaginaries has varied significantly over time and in different cultural contexts, and they have been called upon for a range of different purposes. Saints play different, sometimes overlapping roles in different cultures: as intercessors, friends, protectors, healers, miracle workers, and role models. A small number of saints have relatively global appeal, though the many regional titles given to Mary (e.g. Our Lady of Aparecida, Our Lady of Pilar, Our Lady of Quinche, Our Lady of Czestochowa), or saints tied to national or regional identity (e.g. St. Patrick, St. Alphonsa, or the Ugandan martyrs) evoke special protection for a particular locale, or serve as symbols of a deep and very localized faith. Sometimes the cults that begin as nationalist manifestations end up over time taking on universal appeal.2

The degree of attachment to Mary and the saints varies from country to country. In Mexico, for example, the Virgin of Guadalupe is arguably the most potent Catholic subject of devotion, a protectress of individuals and national identity, a central figure in Mexican culture. In northern Chile, devotion to the Virgin, manifest in dance devotions is so powerful and palpable as to make her seem to be at the center of many Catholics’ faith. In other cultural contexts, the role of Mary in Catholics' lives is harder, even much harder, to discern.

Even where Mary and the saints may be said to draw the same measure of devotion, the reason for the devotion may differ. Mary is described as a mother (usually pictured with the child Jesus), as is almost always the case in India, or as a Virgin (usually pictured alone, as at Fatima or Lourdes), a distinction that is important even though believers would still know that she is regarded as both mother and virgin. Mary has come to represent different ideals of Christian womanhood, as passive acceptor of God's will, or queen, or strong, protective mother.

The story behind the origins of a devotion can be important. Many devotions around images of the Virgin refer to “found images,” images found floating in the sea, in a field, hidden in a cave. In the cases of Our Lady of Montserrat, Our Lady of The Virgin of the 40 Hours in Chile, and Our Lady of Arantzazu, the finding and rescuing of the images is treated as a miracle in itself, a signal of that cult’s authenticity. A significant part of the story of Santiago (St. James) of Compostela is the discovery of his remains in a surprising location.3

The pages below begin to offer a means to understand the different roles of Mary and the saints in cross-cultural comparison. For the saints, a few cultural possibilities begin to emerge:

- In Ethiopia, the saints who figure prominently in people’s lives and celebrations are primarily angels, messengers between humans and God, sure to take one’s prayers to God.

- In Italy, among other countries, saints have often been patrons, often with very specialized roles of mediation.

- In America, among other places, saints for some people are miraculous figures, but perhaps more often are seen as role models, holy persons whose lives might be imitated or at least admired, more important for what we can learn from them than what they can do for us.

- In parts of India like Kerala, the admired saints tend to be guardians from evil forces, like St. George who slays the dragon and protects from snakes.

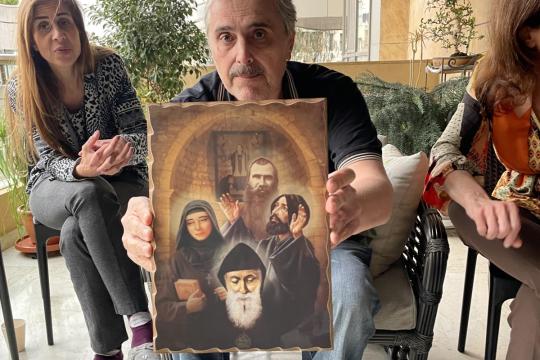

- In Lebanon, saints like Charbel and Rafqa tend to be valued for heroic self-denial and asceticism. Fierce self-denial is still clearly valued in some settings, but gentler forms of renunciation that leads to kindness and generosity is more highly valued.4

- 1For a better understanding of the history and understandings of Christian sainthood in the West in the pre-Reformation and pre-modern era, see Peter Brown, The Cult of the Saints: Its Rise and Function in Latin Christianity (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981), and Robert Bartlett, Why Can the Dead Do Such Great Things?: Saints and Worshippers from the Martyrs to the Reformation (Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2013).

- 2Robert Orsi, “Abundant History: Marian Apparitions as Alternative Modernity” in Moved by Mary: The Power of Pilgrimage in the Modern World (Abingdon: Ashgate, 2009), p. 216.

- 3Peter Brown relates that in the early cult of the saints, the finding of a saint’s body is treated in itself as a miracle. Peter Brown, The Cult of the Saints, p. 92.

- 4Bartlett (p. 634) asserts, at least in terms of studying pre-Reformation sainthood, “Christian saints attained their exalted status and their recognition in society not by taking the ordinary values of that society to a higher degree, but by inverting them. They rejected family, sexual pleasure, and wealth, things that most people desire, and too up lives of self-denial and poverty… To be poor was a misfortune; to embrace poverty was a virtue.” This is undoubtedly true in some contexts, and certainly affirms how socially contextual attachments to saints are. At the same time, Bartlett’s conclusion does not help us understand, e.g., why a sexually open society would not value this inversion.