In the days leading up to January 20, a number of churches in central Kerala are abuzz with activities to honor St. Sebastian. For many Catholics in the region, and some people from other faiths as well, St. Sebastian is regarded as the most powerful heavenly intercessor of all. Prayers to him are considered even more efficacious than those to Jesus and Mary. Accordingly, his parish feasts are among the most elaborate in Kerala, where annual parish feasts are an enormously important part of people’s religious lives.

Why, of all the saints possible, an early Roman martyr-saint would garner that status, particularly in Syro-Malabar (rather than Latin-rite) churches, in areas where the Apostle Thomas himself is said to have evangelized, is a fascinating question.1

The Devotion

In the run-up to the 2018 feast at St. Mary’s Kanjoor, site of a major St. Sebastian feast, a senior priest explained, “I will say, here among the parishioners, they will have more respect for St. Sebastian” than for Jesus or Mary. This is true, he said, “not theologically, but practically… in their heart, at the affective level.” His parishioners, he said, are intellectually quite aware of the relative status of each of those persons in the Catholic theology, but they are equally sure that St. Sebastian has “very powerful intercessory capacities,” particularly when it comes to protecting them from disease and physical calamities. It’s a perspective that they inherited from their parents and grandparents, he said, and they believe that if they ever did something bad against St. Sebastian, “unwanted incidents can happen.”

A man in a different town recalled that in his part of Kerala, north of Kochi, devotion to St. Sebastian began to be celebrated with particular vigor during his childhood in 1953, in the midst of a terrible outbreak of smallpox. The priests, he recalled, brought out an image of St. Sebastian, who had been known as a patron during the European plague, and appealed to him to intercede. Very soon the outbreak fully subsided. The man identified that experience as the source of especially strong devotion in the villages around Kochi. Smallpox has long been eradicated there, but devotion to the saint continues to run strong. Whether for the same reason is unclear, but devotion to St. Sebastian runs strong in some other areas of Kerala, including Arthunkal, Athirampuzha, Bharananganam, and Veli much further south.

Celebrating the Feast

One of the largest of the celebrations is held at St. Mary’s Forane Church, Kanjoor, an ancient, major church (the title, “forane” suggests that a number of other churches fall under its jurisdiction). But a driver passing through the villages around Kochi in mid-January would stumble on many churches and processions. In one day for this research, a Saturday, we encountered four such processions in about an hour and a half on the road. In two cases, at Kanjoor and at St. Sebastian Church, Muringoor, these were very large-scale feasts, while the other two instances, at the Syro-Malabar cathedral in Kochi and at Mary Immaculate Church, Malayattoor, were relatively more modest efforts.2

A procession for St. Sebastian in Kochi, Kerala.

A full-scale parish feast such as those at Kanjoor or Muringoor is preceded by a nine-day novena. At Kanjoor, for example, this is a major event in itself. For nine days, morning and night, in the dark, many thousands gather in a field and in the streets around a roadside shrine for novena prayers and preaching, followed by rather intense fireworks in the field and the sky. Fireworks are an indelible part of St. Sebastian feasts, for reasons that no one could explain. Asked if they served the same symbolic role in Kerala as in China, to scare off evil spirits, most people were dismissive. “People just like it,” the Kanjoor pastor said.

A novena for St. Sebastian at a shrine associated with St. Mary's Forane Church in Kanjoor, Kerala

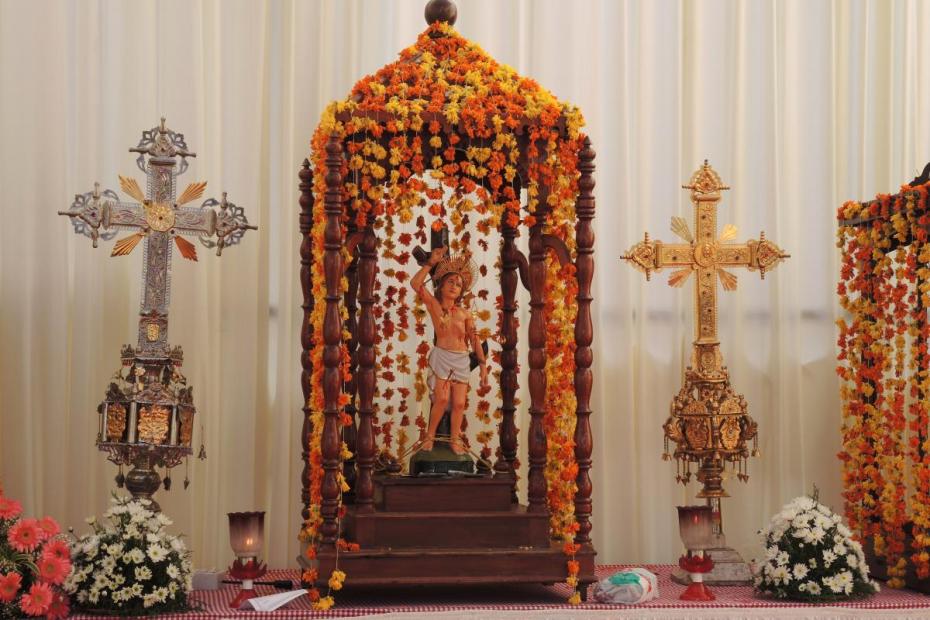

During the novena and during the day before the procession, devotees honor St. Sebastian by bringing up small brass arrows on decorative plates, placing the plates in front of him. The parishes usually own the plates and arrows: at statues in the church or its courtyard, people make a small donation and take a plate, which they leave in front of him. Not long after, the plate is cycled back for another devotee to bring forward as an offering. Some people are able to take the small arrows home for a time. People who spoke about how “powerful” St. Sebastian is as an intercessor insisted that the arrows themselves were not a source of power or a way of bringing home some of St. Sebastian’s power. To carry the arrows is to show respect for his life and witness. One compared the arrows to respect for the Cross, the instrument of death.

Part of the devotion includes bringing decorated plates with small golden arrows to a statue of St. Sebastian.

Posters lined the state highway for a kilometer around Muringoor announcing the event, and posters in many village centers around Kanjoor announced their feast. The local lanes were decorated with tinsel, as were many yards. On the day of the feast, a solemn Mass is held in the church to start the events. The church and courtyard rarely hold more than a portion of those involved in the procession, much less the number of people watching it. Immediately following Mass, the procession begins.

Typically a St. Sebastian procession is led by a band of comprised of drums (chanda), cymbals (elathalam), and long, circular horns (kombu). These traditional, shirtless but costumed, male musical ensembles are an important part of traditional Kerala culture, and are integral to most Hindu, and some Catholic feasts. The procession continues with devotees carrying brightly colored sacred umbrellas and a sea of golden processional crosses. The ornate umbrellas, a symbol from the era of Indian kings, signal the exalted status of the saint. The image of Saint Sebastian, in the largest case, is carried alongside those of the Virgin Mary and the Sacred Heart at the end of the procession at Muringoor, followed by a priest carrying the Eucharist underneath an elegant canopy. At Kanjoor, the image of St. Sebastian, also in the largest wooden and glass processional case, is carried after an image of a crowned boy Jesus, and is surrounded by images of Mary and Joseph. When the image of St. Sebastian is paraded through the streets, it is considered a blessing for all of those who encounter it along the way.

The Muringoor procession, pictured here, began after sunset at 6:45 p.m., following Mass, and finished with fireworks around 9 p.m. The Kanjoor Mass and procession, captured in its entirety on video, lasted nine hours. It, too ended in fireworks.

A procession for St. Sebastian in Muringoor, Kerala.

Feasts of this scale, brought out of the church into the public streets, are inevitably a process of claiming that territory for the revered deity or saint, sanctifying the space to and for the honored saint or divinity. This always has the potential for setting up conflict, which is why many countries downplay such efforts and privatize religion to limited, interior spheres. Interestingly, the feast at St. Mary’s, Kanjoor, attracts people from a wide variety of faiths, and engagement with local Muslim and Hindu leaders is built into the planning. In the days before, a number of delegations from the other faiths came to the church and were invited to lunches and planning meetings, and encounters with them seemed especially harmonious. A swami and an imam shared messages at the opening celebration, professing peace and harmony, emphasizing practical encounter over theological dialogue.

- 1Syro-Malabar churches grew out of Syrian and Indian historical contexts, not Roman ones, though of course they were later influenced by Portuguese and Roman traditions. Even as the Syro-Malabar church seeks to highlight and recover the Syriac facets of their liturgical tradition from Romanization, churches and the people focus their attention to a saint whose cult grew out of the Roman Empire, in Catholic and Orthodox Europe. Beyond telling the historical story of how he came to be revered in Kerala, the interesting question is also why he continues to have such ongoing power in these communities today.

- 2Had our car traveled only another kilometer away, we would have come to another Catholic church, dedicated to St. Sebastian, which had its own parish feast. Ironically, the Malayattoor churches are within walking distance from a celebrated mountain that the Apostle Thomas is said to have climbed, and a bend of the river that is home to a major shrine church to St. Thomas. Thomas surely has pride of place in that particular area, but St. Sebastian is not too far behind. On that day, though, the designated Thomas shrines had only a few people, while people prepared to celebrate St. Sebastian.