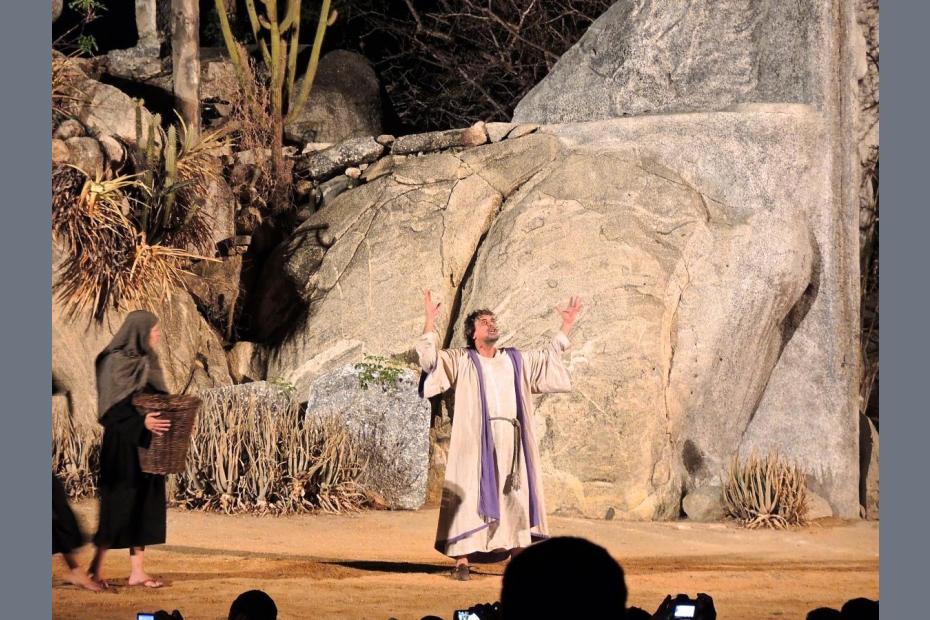

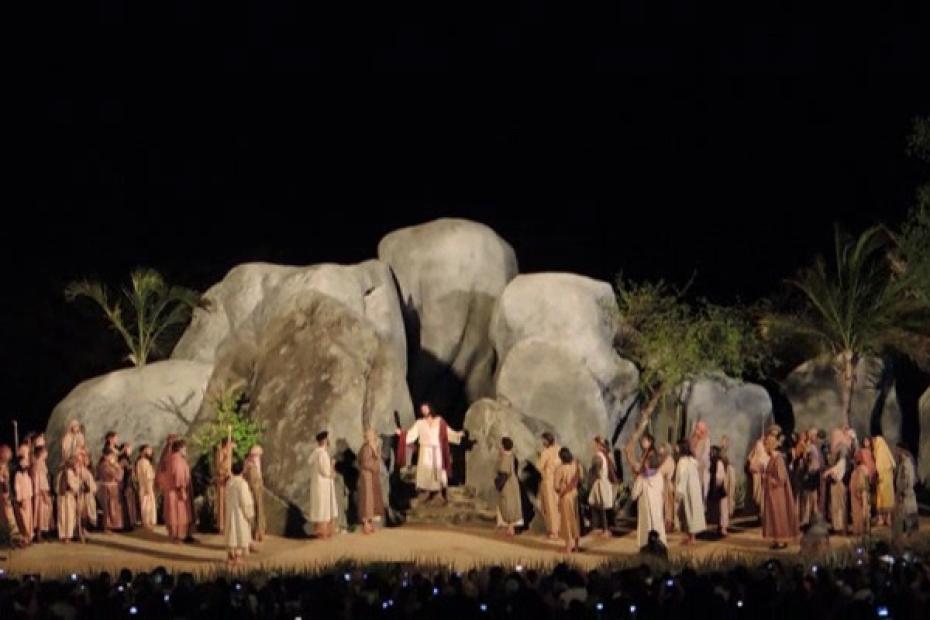

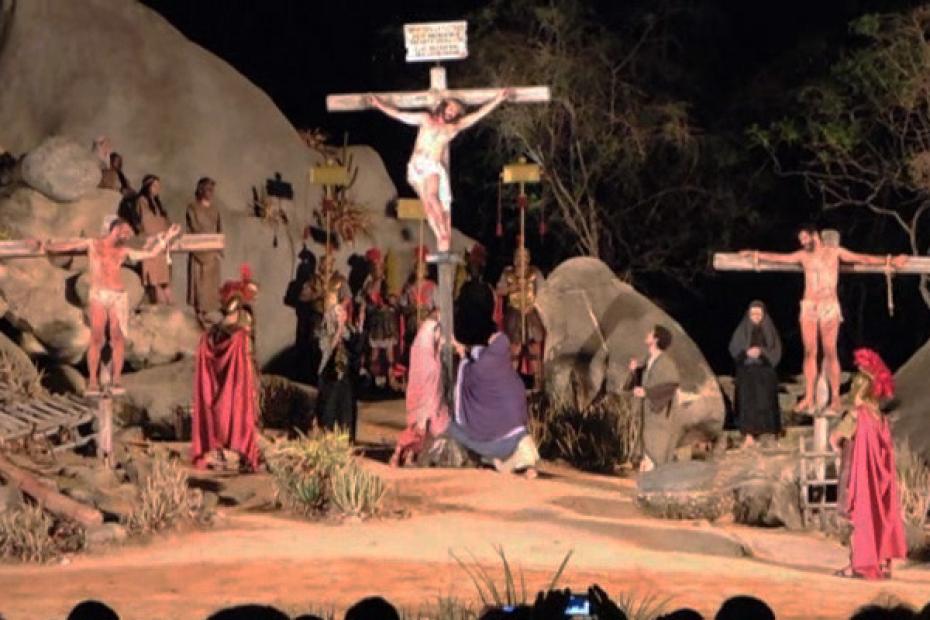

In Nova Jerusalém, a specially constructed theater about 200 kilometers west of Recife, the annual Paixão de Cristo – the Passion of Christ – reenacts the events of Holy Week on a scale befitting the biggest of Hollywood spectacles. Located on huge, fortress-style walled grounds with nine massive stage sets, Nova Jerusalém is built exclusively for the passion play and claims to be the largest outdoor theater in the world, “a city theater 100,000 square meters in size, equivalent to a third of the original walled area of Jerusalem.”1 The play, which lasts two hours, features a cast of 50 actors, many of them television celebrities, plus horses, chariots and 500 elaborately costumed extras. It draws crowds of 10,000 or more to an isolated desert community each night during Holy Week.

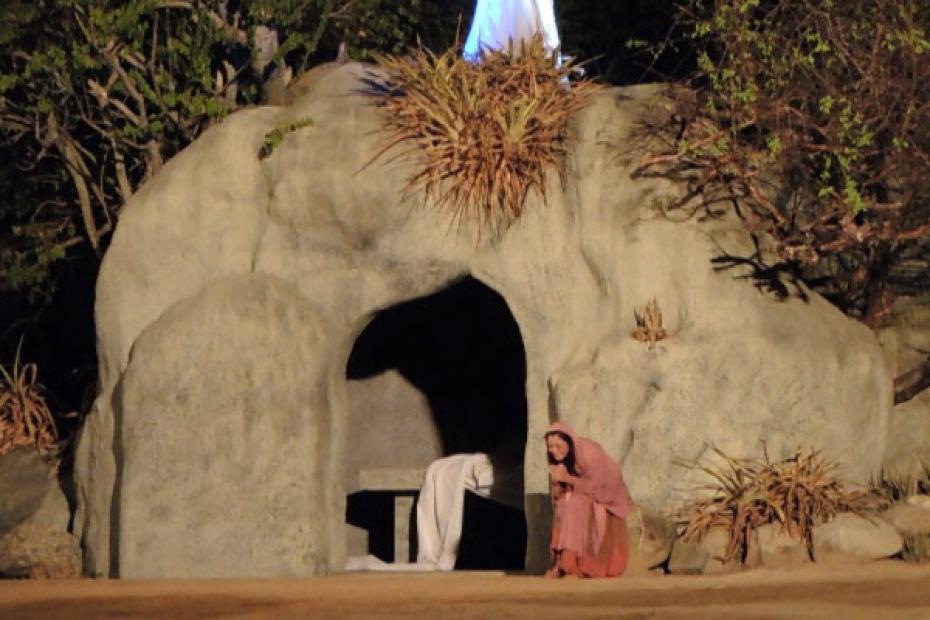

Given the topic — Jesus’ suffering and crucifixion — the play certainly has its powerful, low moments, but the feeling at the Paixão is not dour or doleful in the way many passion reenactments can be. The Paixão is even promoted as something different: “an opportunity for the audience to live and relive the thrills of a grand spectacle which tells the life of Jesus, the character most prominent in the history of mankind.”2 The experience begins and ends outside the theater in a massive plaza with carnival-like tents, shopping and gatherings of acquaintances glad to see one another. At the end of the play, an audience who has cheered at Judas’ suicide and the Resurrection has even wilder applause when some of the main actors take their bows and mug for photos. People line up for smiling photos at the exits with some of the centurions who just finished convincingly playing the bad guys in the spectacle.

The spectacle

The play itself lasts for two hours, beginning at dark, but people begin arriving hours earlier. The area between the parking lot and the entrance has a festive, carnival-like quality. People gather there early under a string of huge tents that sell fast food, local crafts and an array of inexpensive items like handbags and shoes.

Inside the theater, the play moves among nine elaborate sets, beginning with the Sermon on the Mount and an exposition of Jesus’ message. Each set has a viewing area that can accommodate more than the 10,000 people there that night. Other scenes include the Temple of Jerusalem, the Last Supper, the garden of Gethsemane, Herod’s palace, the Roman Forum, the Way of the Cross, the Crucifixion at Calvary, and the entombment and Resurrection.

Audience

On the Monday of Holy Week in 2013, a crowd of about 10,000 people, mostly people aged 15-50, filled the theater. Typical clusters of participants included young couples holding hands, groups of teenagers, and small church groups of adults, many in parish t-shirts. Perhaps because of the scale of the place and the need to move quickly from scene to scene in the dark, there were not many small children, and not many elderly, though there was a wheelchair battalion to move some 50 wheelchairs from place to place.

The crowd included both Evangelicals and Catholics. Of 25 people interviewed outside of the theater that evening, almost every one had seen the Passion here at least once already, a few as many as five times. All of them said they were there for the “meaning” of the event, not the actors, and everyone indicated that most people they knew had seen it. Most participants seemed to be middle class, which is not surprising given the price of the tickets (about US$30 each for adults).

Most of the Catholics interviewed described themselves as committed to their faith, but not the most fervent people they knew. When asked what made a person a good Catholic, they seemed eager not to judge, but suggested that the most important qualities were a willingness to share, to care for those in need, and to go to Mass. Some belonged to small prayer groups, but most said as family people in modern society it was hard to keep up regular commitments, whether to prayer at home or to groups at the parish. Those who self-identified as “strong” Catholics frequently described themselves as “more conservative,” especially compared to urban Brazilians in the South, but it was not always clear what this meant. To most, it seemed not to be a political statement, but had to do with “keeping the traditions of the church” and with sexual morality, though it was always notable even then, the teenagers in the groups were seldom dressed conservatively.

Catholic interviewees at the Passion all knew people who had become Evangelical Christians. Most tended to ascribe this to a Church that was not always there for those people when they needed it, but few were concrete why. Despite the fact that Brazilian census show a notable decline in attachment to the Catholic Church over the last 40 years, all of the adults suggested that they saw no diminution of the faith since their youth, and that their parishes had plenty of active young people.

Commerce and Faith

One of the most interesting paradoxes of the evening was the degree to which commerce and religion are woven together at Nova Jerusalém. In the play, Jesus very convincingly chases the money-changers out of the temple, an event pictured as a key cause of his troubles, but in Nova Jerusalem, commerce is a significant part of the evening. Tickets and t-shirts are expensive, which is not surprising given the cost of production. Beyond that, though, corporate sponsors feature their brands in advertising on large video screens at the start of the event, and elsewhere on the advertising posters. Even the play’s website suggests that the founders of the event in the 1950s hoped that it would “attract tourists and thus promote trade” there.3 The tents outside especially commercialize the event, though here it is on a local, not a corporate level.

Part 1 of 3: Paixão de Cristo, Nova Jerusalém, 2013

Part 2 of 3: Paixão de Cristo, Nova Jerusalém, 2013

Part 3 of 3: Paixão de Cristo, Nova Jerusalém, 2013

- 1Paixão de Cristo de Nova Jerusalém — Pernambuco, last accessed July 30, 2013, http://www.novajerusalem2013.com.br.

- 2Paixão de Cristo de Nova Jerusalém — Pernambuco, last accessed July 30, 2013, http://www.novajerusalem2013.com.br.

- 3 Paixão de Cristo de Nova Jerusalém — Pernambuco, last accessed July 30, 2013, http://www.novajerusalem2013.com.br.