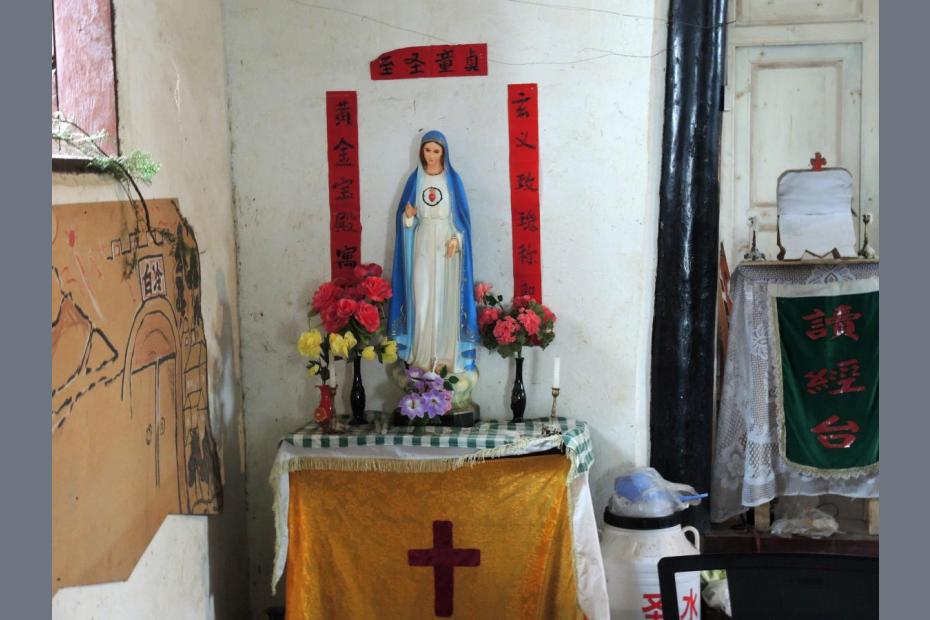

The constellation of saints in China is, in practice, quite narrow. Observant visitors to Catholic churches in China would be struck to notice how frequently, in addition to the Crucifix or the Sacred Heart, one sees statues of Mary and St. Joseph — with Mary on the left and Joseph on the right as one faces the altar. These images, especially the Sacred Heart and the Immaculate Heart of Mary, are manifestations of forms of Catholic piety that endure from before China was cut off from the rest of the Church. Chinese Catholicism was shaped by the 19th century French missionaries who brought images of the Immaculate Heart of Mary and St. Joseph alongside images of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. The European images remain prominent in Chinese Catholic churches and homes today. Nonetheless, the other Catholic saints who had popular followings before 1949 (and those who became more popular since) are generally absent. Asked about that, one priest in Yunnan replied, “That’s true. I don’t know why,” and confirmed that the saints were largely absent not only visually, but in terms of devotion. St. Joseph and Mary are patron saints of China, which explains in small part why they are so prominent, but St. Francis Xavier, who was also designated as a patron, is largely not visible today.

Marian devotion is strong in China, both in terms of local manifestations and in terms of the importance of shrines like Our Lady of Sheshan near Shanghai and the Our Lady of China at Donglu in Hebei Province.

Richard Madsen has commented on the affinities between the “Eternal Mother” of folk Buddhism and Mary in Chinese Catholicism, “who is often depicted in robes like those of a Chinese goddess.”1 Madsen reports instances of Marian apocalypticism but, based on his research in the rural Hebei province, also contrasts Catholic villagers’ understanding of God as a “stern accountant” to the “warm and compassionate dimension of the sacred [they perceive] in the Virgin Mary. The central pictures in most rural churches and most true-believing Catholic homes are of the Blessed Virgin. According to many of those with whom we spoke, the primary focus of belief is not God the Father but Mary, ‘who is our mother.’ The Marian cult was central to the theology conveyed to China by 19th- and 20th-century European missionaries. Mary — gentle compassionate Mary, portrayed even in Chinese households as a slender, brown-haired European woman dressed in blue, often openly displaying her Immaculate Heart — is primarily the one who helps us in our trials, defends us from our enemies, heals us when we are sick, and keeps us from sin.”2

Elsewhere, Madsen writes, “Although, remembering their catechisms, true-believing Catholics say that the sacraments, properly administered by a priest, are the primary channels of grace, they in practice rely on Mary to give them a chance at heaven. One colloquial name for Catholics in the north China countryside is ‘Old Rosary Sayers.’ Certainly, they spend much more time saying the rosary to Mary than going to Mass.”3

A good many of the Church’s saints have been martyrs, and Madsen notes that political reasons prevent Chinese churches from honoring martyrs. Martyrdom is a subversive concept in China, and the government “claims that Catholic martyrs are not religious loyalists but political subversives, not persons of exemplary character but traitors to the state. Interfering with the traditional Church calendar, the Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association has gone so far as to eliminate all feasts of the martyrs from the liturgical year.”4 Nonetheless, this reasoning cannot account for the paucity of non-martyr saints in Chinese Catholic life.

- 1Richard Madsen, “Beyond Orthodoxy: Catholicism as Chinese Folk Religion” in Stephen Uhalley, Jr. and Xiaoxin Wu, eds., China and Christianity: Burdened Past, Hopeful Future (Armonk and London: M.E. Sharpe, 2001), 242.

- 2Richard Madsen, China’s Catholics: Tragedy and Hope in an Emerging Civil Society (Berkeley: University of California, 1998), 86, 88.

- 3Richard Madsen, China’s Catholics, 90.

- 4Richard Madsen, China’s Catholics, 84.