San Michele on the Gargano is a shrine on a hill above the Adriatic Sea on the spur of Italy's boot. Dedicated to the Archangel Michael, it seems at odds with the post-Vatican II Church in Europe, but in fact is crowded with visitors who come for more than the medieval ambience of this hill town. Stores throughout the town sell copies of the statue at the center of the shrine, an androgynous white marble angel in Roman soldier's clothes, with a gold crown and wings, ready to strike a golden sword against a devil who is kept on a golden leash. The statue is dressed with a changing array of gold jewelry.

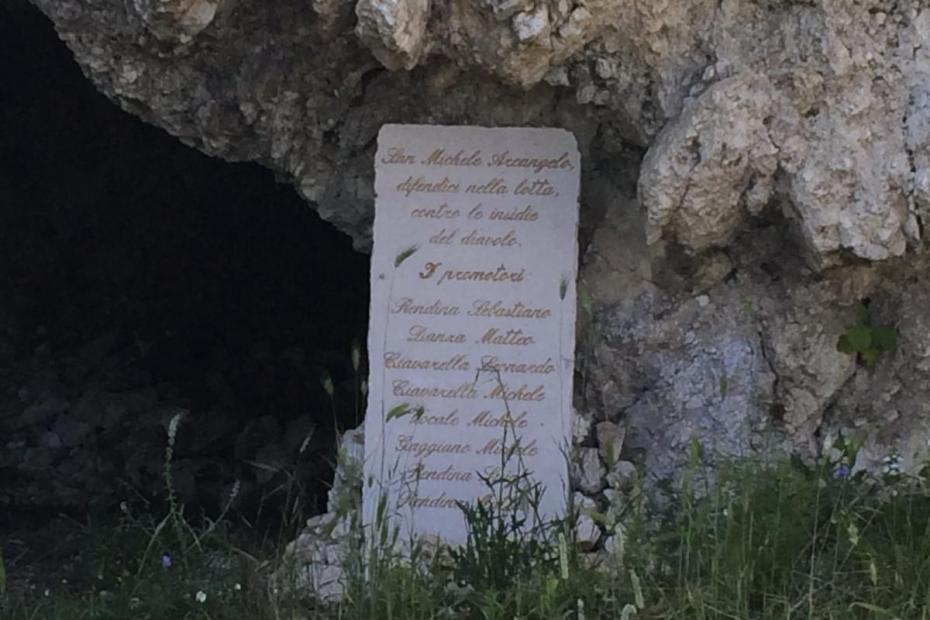

The legend behind the cult begins with a fifth century herdsman whose bull disappeared into a cave. The herdsman shot the bull with an arrow, but the arrow came back and hit the herdsman instead. Perplexed, he told the bishop about this, and three days later the bishop had a vision of the Archangel Michael, who claimed the cave as sacred to him, saying “Where the rock opens wide, the sins of men can be forgiven. What is asked for here in prayer will be granted. Therefore go to the mountain and dedicate the grotto to the Christian religion.”1 Subsequent legend has it that when the bishops traveled to consecrate the cave themselves, they found that the Archangel Michael had already visited the shrine and dedicated an altar there himself. The archangel is said to have subsequently protected the town from an overwhelming siege.

The reference to caves and bulls almost certainly references (or enabled) the triumph of Christianity over Mithraism, the mystery religion of the Roman Empire. In the founding narrative of that religion, the god Mithras subdued a bull and brought it to a cave to be slayed. Mithraic rituals involved slaying bulls inside caves or underground temples. The traditional accounts of the founding certainly seem to suggest the site’s successful reconsecration as a Christian site.

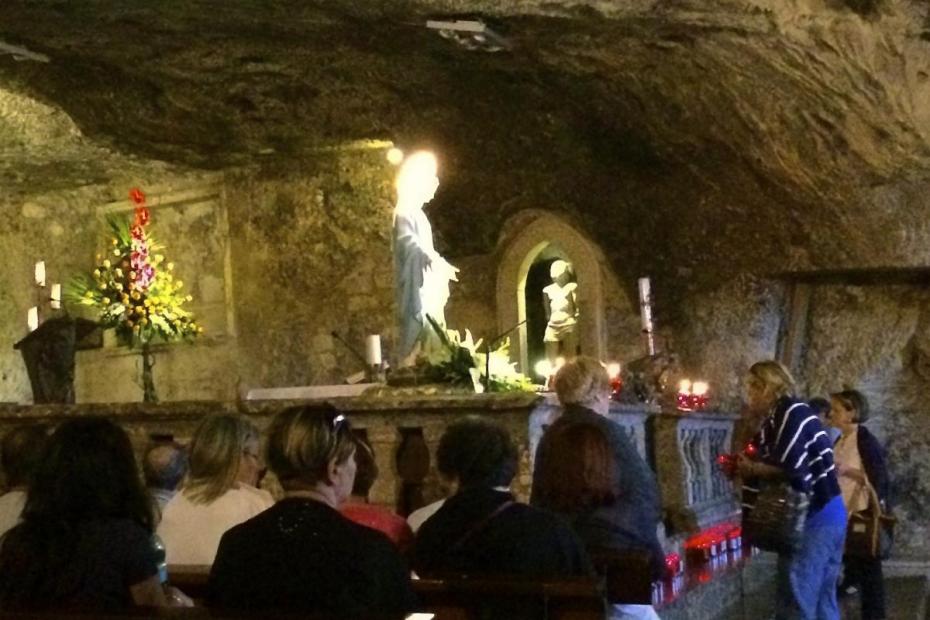

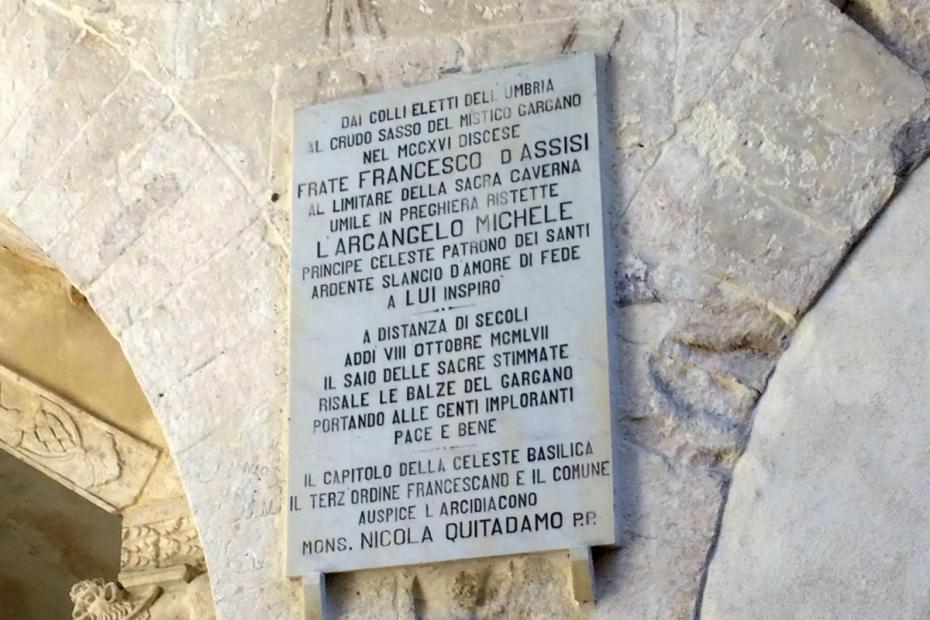

San Michele developed into a fairly important medieval shrine, visited by kings and saints and commoners. But the cult of San Michele hardly seems like one that a person might expect to thrive 50 years after Vatican II. With its medieval buildings, including the shrine, one might expect that Monte Sant’Angelo, the town that grew up there, would be a good tourist attraction whose religious appeal had faded. Yet this hardly seems to be the case. Carloads and busloads of tourists continue to come to town. But interestingly, they all bypass the castle museum at the top of the hill and a number of other high quality (mostly free) medieval sites, heading past religious souvenir shops and restaurants, straight down the stairs to the cave, like good pilgrims. Many are on pilgrimages that have taken them to the nearby shrine of Padre Pio. The shrine in itself could be a great teaching site for an art history class, but seems instead to be very much a devotional site. Pilgrims typically spent considerable time praying in pews, at various statues and altars in the grotto, and at Mass there. Interestingly, a statue of the Immaculate Conception is placed at the front of the Archangel Michael in the sanctuary. It is an unusual image for Italy, since she is not a Madonna with child. Despite her presence, pilgrims said they come to honor the Archangel. Interestingly, Immaculate Conception statues are not in evidence in the souvenir stores in town, where the Archangel Michael is ubiquitous, followed by Padre Pio. A small museum of ex votos on site gives witness to a long history of favors received through the intercession of St. Michael.

- 1P. Jan Bogacki, Saint Michael Shrine on the Gargano, trans. Christine Fesq, no. 95, 5th edition (Edizione d'Arte Marconi, 2009).