The island of Sri Lanka lies off the coast of India. It is officially a democratic socialist republic and has an ethnically and linguistically diverse population of over 23 million people. Seventy-five percent of Sri Lankans speak Sinhala; Tamil-speaking Sri Lankans are the largest minority, constituting approximately 11 percent of the population. Buddhism is practiced by 70 percent of the population; Hinduism by 12 percent; Islam by nine percent. A little over seven percent of Sri Lanka’s population is Christian. Of these, the vast majority is Catholic.

As in India, the subject of pre-colonial presence of Christianity in Sri Lanka is a matter of debate and speculation. For example, former Archbishop Oswald Gomis argues that St. Thomas and Nestorian Christian communities existed in Sri Lanka during the early centuries of the Common Era.1 There are reports of Christian advisors to Sri Lankan rulers as well as the presence of Christian mercenaries.

The Portuguese came to Sri Lanka in 1505 and established trading relations with King Vira Parakramabahu VIII. The Portuguese intervened militarily during a succession struggle after the death of King Vijayabahu VI and established a strong presence in Kotte, which came to be ruled by a Catholic king, Don Juan Dharmapala. Kotte became a suzerainty of Portugal after King Dharmapala’s death. While the Portuguese were displaced by the Dutch as the preeminent colonial power, a significant Catholic community remained along a coastal belt, extending from the Sinhalese speaking Colombo/Negombo area in the South through the Tamil speaking Mannar area in the north.

Catholics were privileged under British colonial rule and prized their separate, distinctive identity. For example, during the week celebrating independence, Catholic families were encouraged to display the Papal flag along with the lion standard of Sri Lanka. Catholic influence began to diminish when the Sri Lanka government took over Catholic schools in 1960 and in the wake of an abortive coup in 1962, planned by Catholic officers in the Sri Lankan army who feared loss of influence to increased Buddhist presence in the military.

After the anti-Tamil pogroms during “Black July” 1983, a civil war broke out between the secessionist Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam and the Sri Lankan government. The war ended in 2009 but left lasting scars on Sri Lankan society and the Catholic Church. Eight Sri Lanka Catholic dioceses are in Sinhala speaking areas; four in Tamil speaking regions. Sri Lankan Catholic bishops publicly disagreed with Tamil bishops who put forward a humanitarian proposal for a cease-fire during heavy fighting in 2008 — not one bishop from a Sinhala-speaking diocese supported this effort. Presently, the focus is on healing and reconciliation, which also was the primary purpose of Pope Francis’s visit to the island in January 2015.

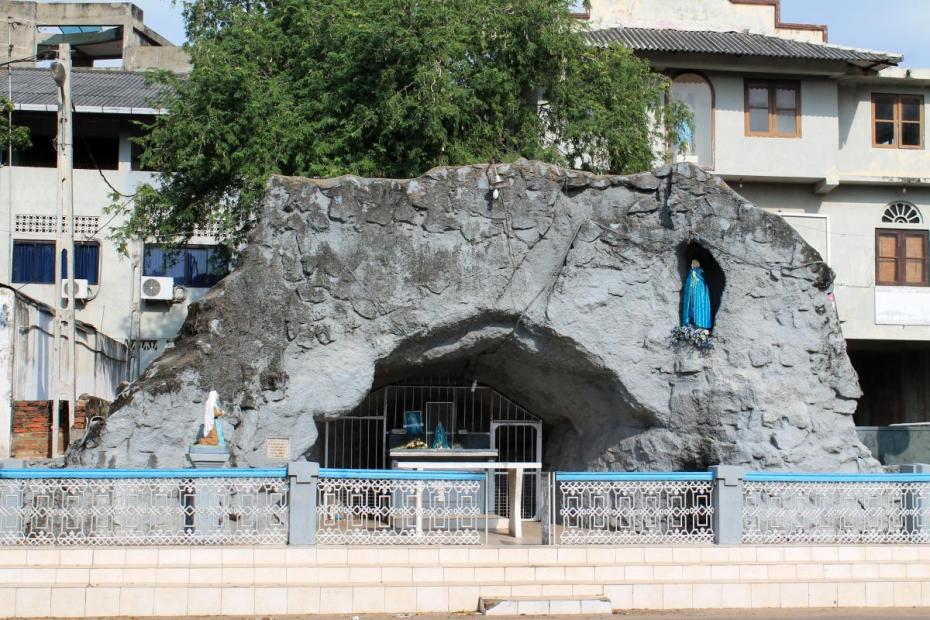

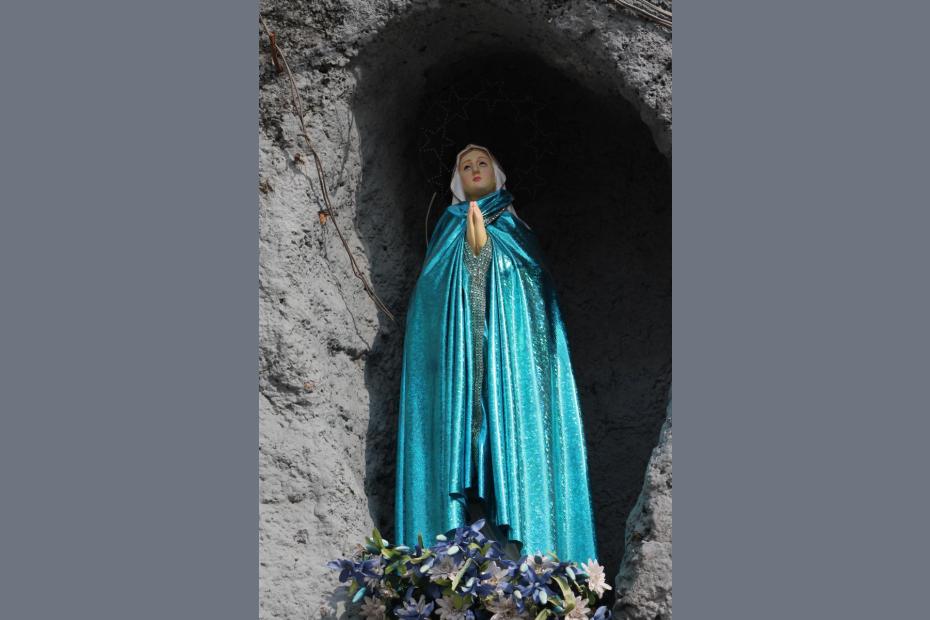

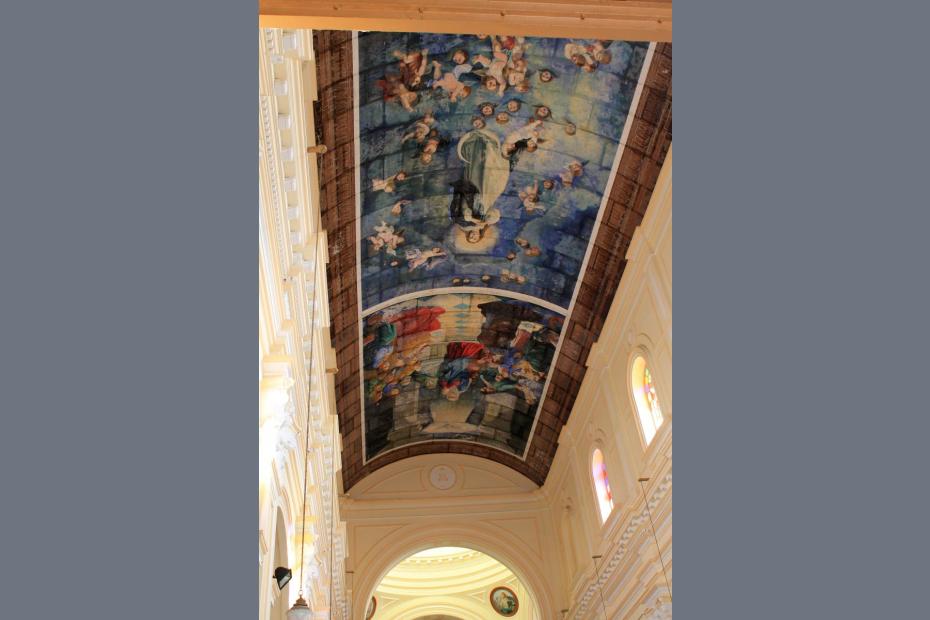

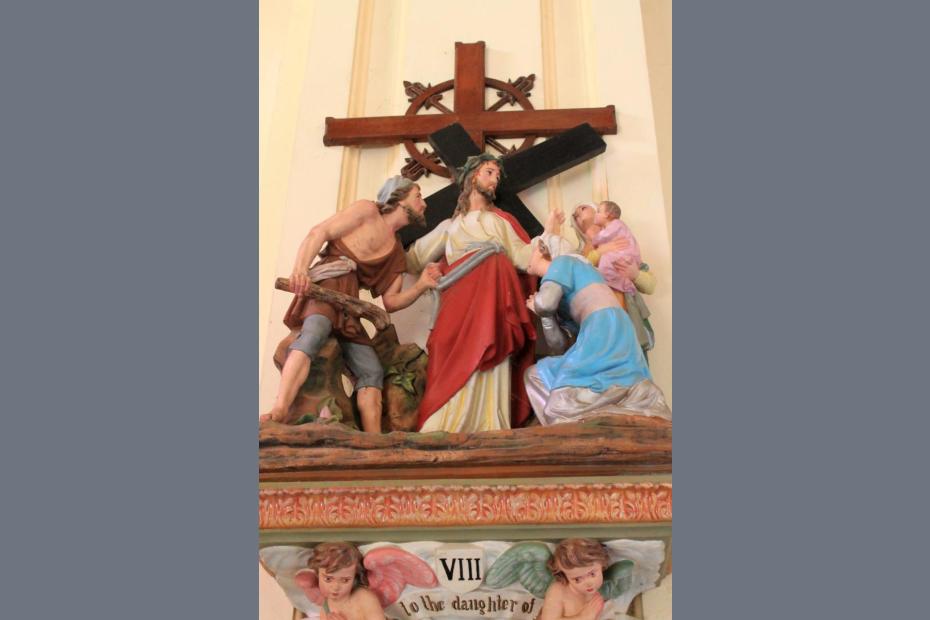

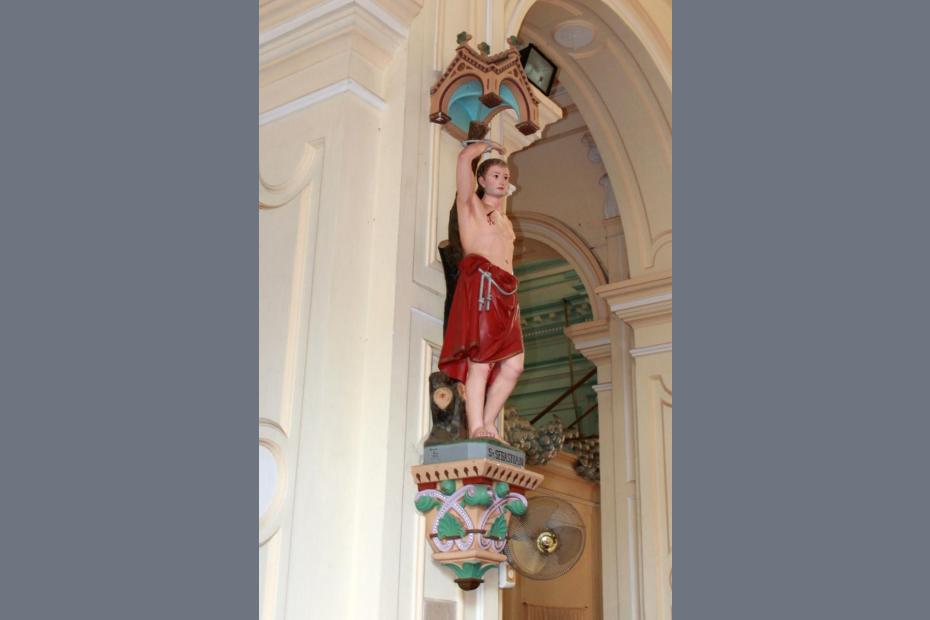

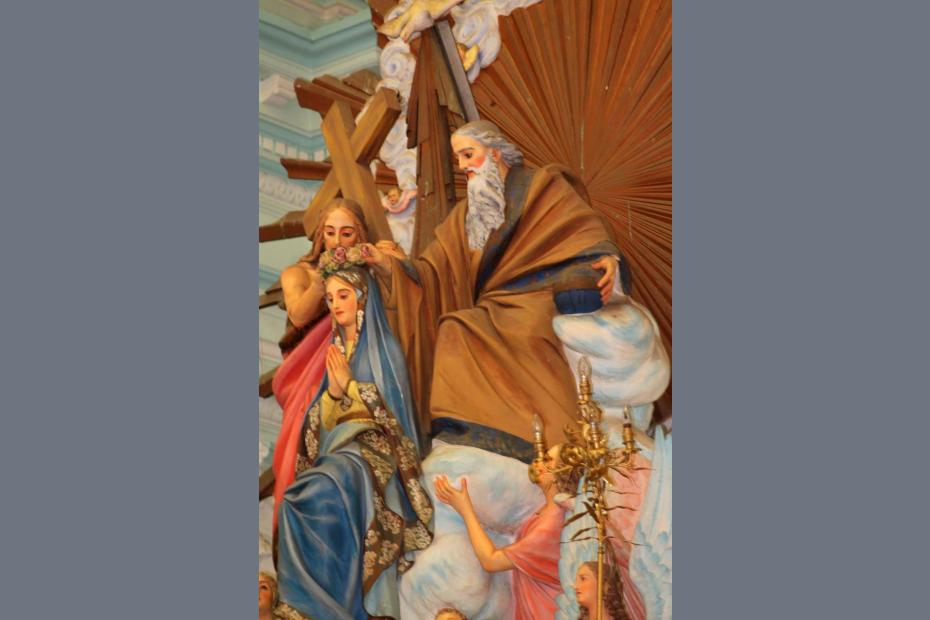

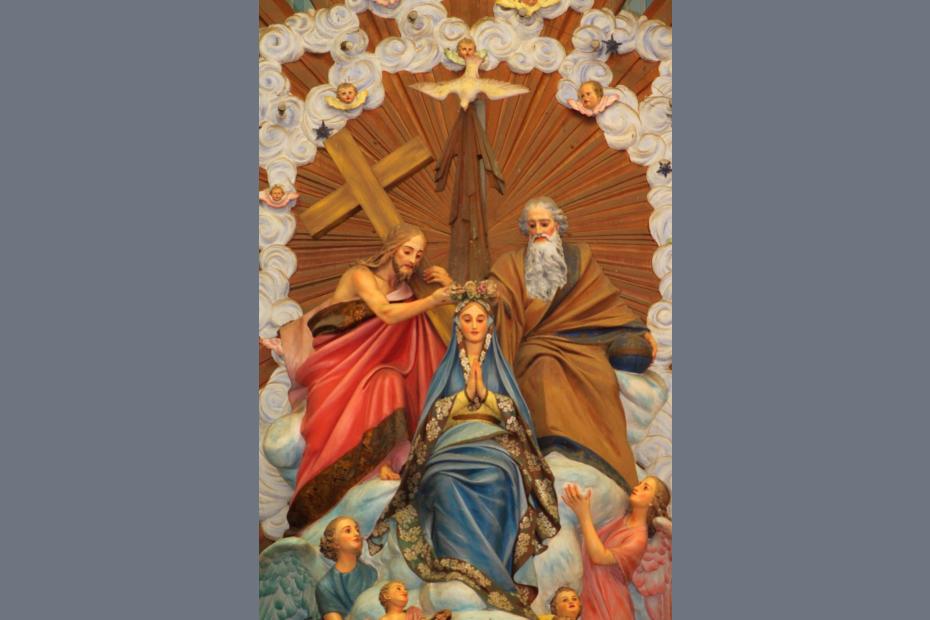

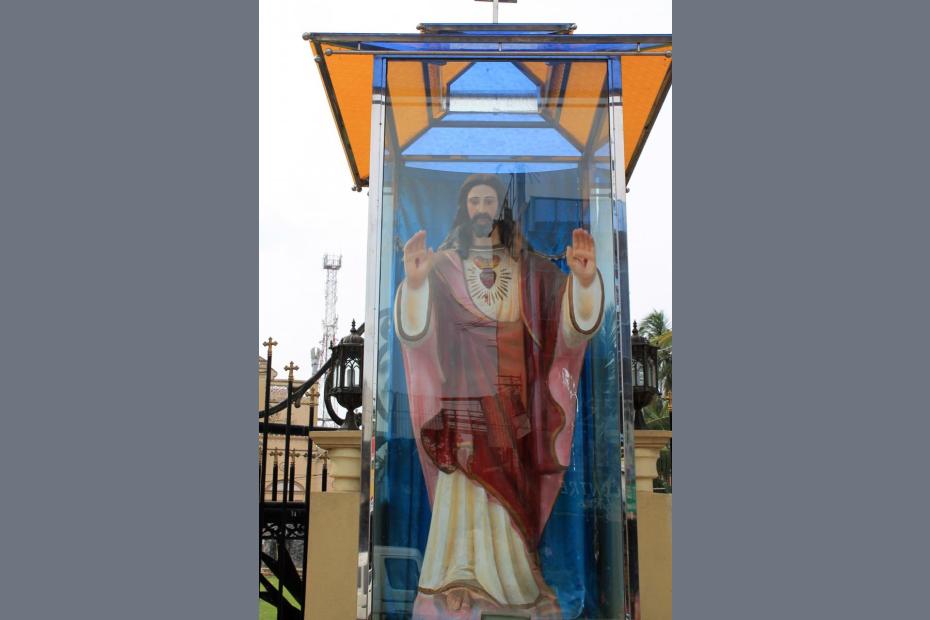

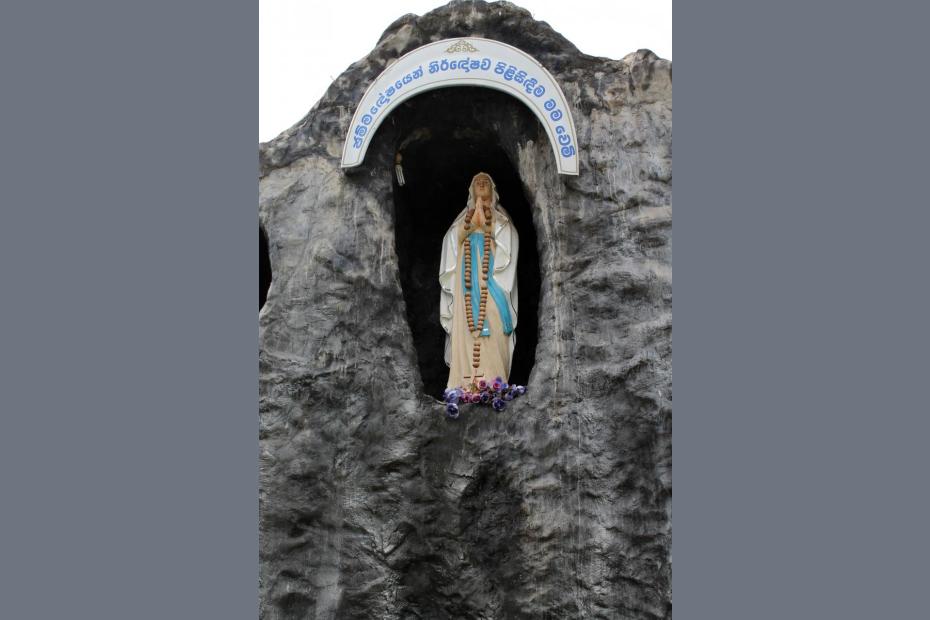

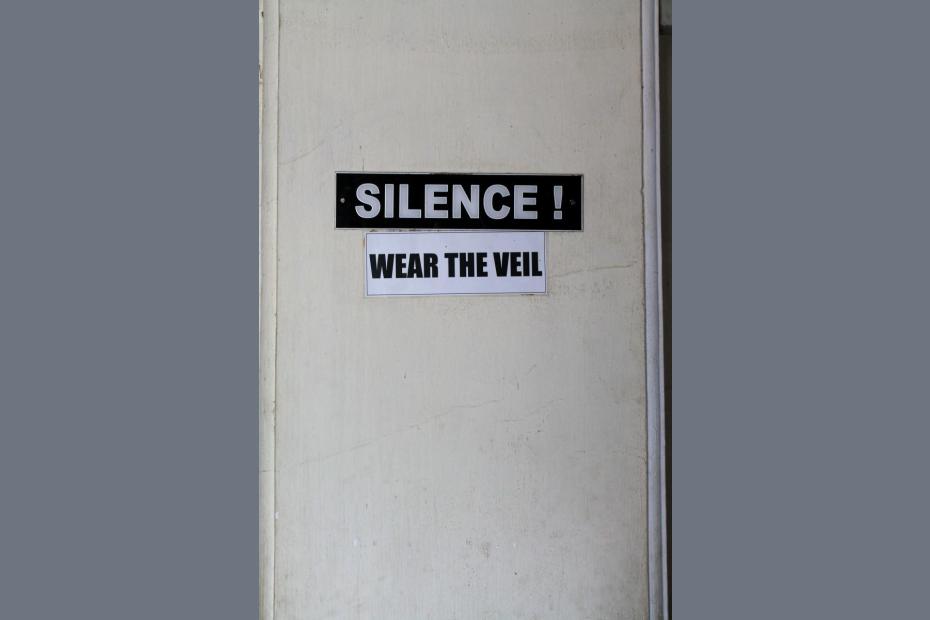

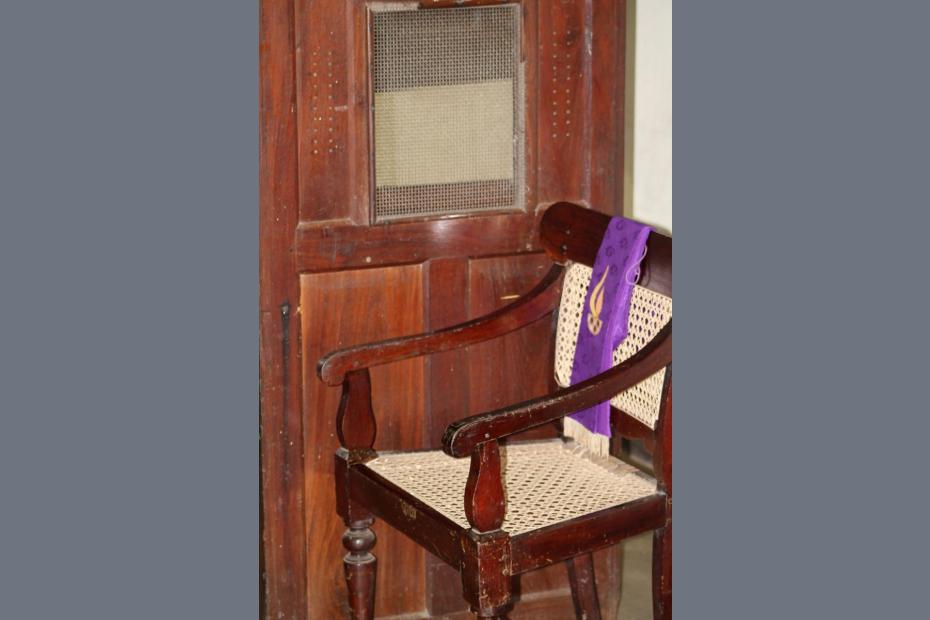

Sri Lankan Catholic culture is distinctive. Veiling is required for women in church, and many individual churches have an ornate, European-influenced, style. Most churches have a Lourdes grotto, honoring Mother Mary. A famous example of this style is St. Mary’s church in Negombo, which has an elaborate altar depicting the coronation of Mary in heaven. Processing toward the altar is an “arcade” of European saints and an elaborately painted vaulted ceiling. The Church of the Holy Spirit in Kochchikade is less ornate but also has a grotto, along with side shrines where candles are lit and monetary offerings made for intercessions and particular favors.

Alms giving, both after a funeral and on pilgrimage, is an important part of Sri Lanka Catholic culture, as it is among the island’s Buddhist community. As in many parts of India, regulations for marriage are quite strict: the parish priest will announce a couple’s engagement and invite parishioners to “make a complaint” if warranted. In Tamil speaking areas, the thali necklace is tied to the bride as a sign of matrimony. Also, in Tamil speaking areas, caste affiliation is quite important, and inter-caste marriages are often discouraged.

Further Reading

Bernardo Brown, “Sinhalese and Tamil Catholics, different paths to reconciliation,” IIAS Newsletter 69 (Autumn 2014).

Paul Caspersz, S. J. “Christians in a Buddhist Majority,” in The Sri Lanka Reader: History, Culture, Politics, ed. John Clifford Holt (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2011), 560-66.

Robert Stirrat, Power and Authority in a Post-Colonial Setting (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992).

- 1Oswald Gomis, Lakmathawa ha Katholika Sasuna (Colombo: 2004)