Portuguese settlers conquered Brazil more than 500 years ago, institutionalizing the faith there. Stylistically, though, contemporary Brazilian and Portuguese Catholicism are quite different. Brazilian culture has been significantly defined by indigenous people (especially in the interior regions and Amazonia), by Africans brought there during the slave trade (especially in the Northeast coastal regions) and by immigrants from many European countries, including Germans and Italians who settled in the South. In light of this, one might speak of Brazil as the home of three regional Catholic cultures: a metropolitan, largely urbanized, European-inflected culture in the south; an African-inflected culture in the northeast; and an indigenous-inflected culture in the interior and Amazonia.

Brazilian Catholicism has also been shaped by the context of its recent history, leading to the development of three other “styles” of Brazilian Catholicism. Throughout much of the 20th century, repressive governments and tremendous income inequality led to a proliferation in the 1970s of Base Christian Communities grounded in liberation theology. At the same time, other Brazilians found solace in more traditionalist modes of Catholicism that avoided the radical social conclusions of liberation theology. More recently, after a transition to democracy, Brazilians have sought to overthrow vestiges of their past, as Brazil integrated into global capitalist markets, adopted the ethics of capitalism and grew into the seventh largest economy in the world. That process has coincided with the rise of American Pentecostal-style religion, and also with a significant increase in religious non-affiliation. It also helped till the ground for development of a Charismatic style of Catholicism.

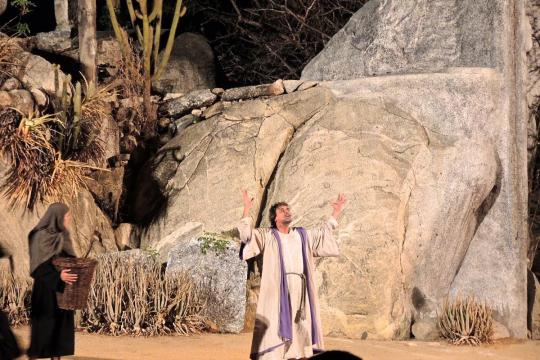

In some ways, Brazilian Catholicism is marked by a variety of forms of religious spectacle, whether in the form of traditional public festivals and processions, the 45,000 seat shrine for Our Lady Aparecida, the stadium-sized spectacles of charismatic Catholicism, or the film-studio perfection of a massive outdoor event like the Paixão de Cristo in Pernambuco. Yet as one of the birthplaces and centers of liberation theology, Brazil is equally home to less spectacular but no less influential forms of Catholicism. There, in tiny Base Christian Communities, Catholics meet to read the gospel and to discuss it in light of the poverty and injustice they see around them.

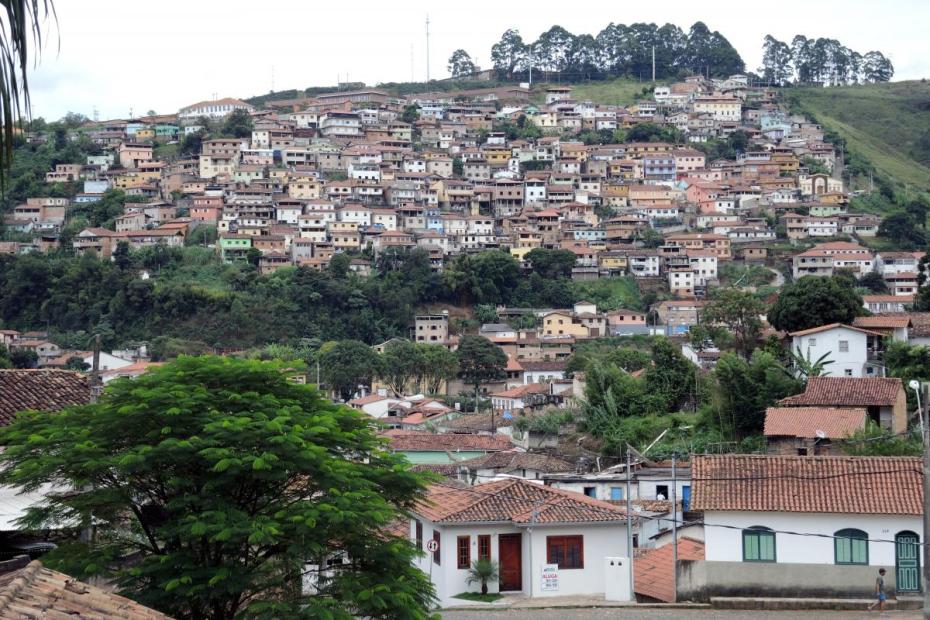

The overwhelming majority of the Brazilian population lives in cities, including megalopolises like São Paulo, with a metropolitan area population of nearly 20 million people, and Rio de Janeiro, with nearly 12 million people. Until the 1950s, 85 percent of the population was in rural areas. Today 87 percent are in urban areas. These are among the most congested and expensive cities in the world, but alongside that wealth is still great poverty. A massive migration to the cities since the 1950s brought many people into the massive favellas, or slums, squatter areas that grew up on hills of cities. Ranked among the most violent places in the world, favelas have operated as parallel societies, often run by drug traffickers and completely unserved by government. The government is making slow progress pacifying the favelas, but in most, still, the police cannot enter safely.1 Not surprisingly, they are underserved by the Church. Catholicism holds on to the rural areas to a greater extent, with 78 percent of the population identifying as Catholic, compared to 62 percent of the urban population. Urban residents are almost twice as likely (9 percent) as rural residents to be religiously unaffiliated.2

A 2024 study by Pew Research Center reported that 63% of Brazilians thought that the Church should allow Catholics to use birth control, 83% that the Church should allow women to become priests, 59% that it should allow Catholics to take communion even if they are unmarried and living with a romantic partner, 50% that they should allow priests to get married, and 43% that they should recognize the marriages of gay and lesbian couples.15

Evangelical and Secular Inroads

Catholicism’s hold on Brazilian society is far weaker than it was a few decades ago. As recently as 1970, 92 percent of the population identified as Catholic, whereas today the proportion stands at 65 percent. Since 1970, the number of Protestants has jumped from 5 percent to 22 percent, and the number of religiously unaffiliated Brazilians has jumped from 1 to 8 percent.3 The number of Brazilians in other religious categories, including Spiritists and Afro-Brazilian revival movements, has also increased in recent years.

Evangelical and Pentecostal churches account for almost all of the growth in Protestantism in Latin America. 62 percent of Pentecostals studied in 2013 did not grow up as Pentecostals, and nearly half of Pentecostals (45 percent) are converts from Catholicism.4 The shift to Pentecostalism is more marked among urban residents (24 percent of whom describe themselves as Pentecostal) than among rural residents (15 percent of whom describe themselves as Pentecostal).

A December, 2016 study by Datafolha, a prominent Brazilian survey firm, claimed that Catholics now comprised only 50% of the population aged 16 or older. The survey said that 29% of Brazilians are Evangelical, 14% without a religion. Only 1% claimed to be Candomble practitioners, and 1% to be atheists. Almost half of Evangelicals in the survey said that the had no religious practice beforehand. Catholics were said to be much more likely than Evangelicals to see all religions as equally valuable because they lead to the same God.5

A second aspect of the Datafolha study highlights a significant prosperity strand in Brazilian Christianity: asked whether they agree that "all of my financial success comes first from God," 87% of evangelicals fully agree with the statement and 7% agree in part. Among Catholics 78% totally agree and 13% agree in part. Strikingly, each group is more likely now to believe that God's reward is prosperity on earth than it is to believe it is everlasting life in heaven. Asked whether "those who believe in God, when they die, will go to heaven and have eternal life," 72% of Evangelicals fully agreed with it, and 15% agreed in part. Among Catholics, these rates were 61% and 19%, respectively.6

- 1 An excellent and brief description of the favelas in English is provided by Suketu Mehta, "In the Violent Favelas of Brazil," in The New York Review of Books, August 15, 2013, accessed August 29, 2013, http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2013/aug/15/violent-favelas-brazil/?page=1.

- 2Pew Research Center, "New Report Details Brazil's Changing Religious Landscape," July 18, 2013, http://www.pewforum.org/2013/07/18/new-report-details-brazils-changing-religious-landscape.

- 3

Pew Research Center, "New Report Details Brazil's Changing Religious Landscape," July 18, 2013, http://www.pewforum.org/2013/07/18/new-report-details-brazils-changing-religious-landscape. - 4 Lugo, Luis, and Andrew Kohut. "Spirit and Power: A 10-Country Survey of Pentecostals." The Pew Forum On Religion & Public Life (2006): 32. https://www.pewforum.org/2006/10/05/spirit-and-power/ (accessed November 21, 2021).

- 5Datafolha, "44% dos evangélicos são ex-católicos" http://datafolha.folha.uol.com.br/opiniaopublica/2016/12/1845231-44-dos-evangelicos-sao-ex-catolicos.shtml December 28, 2016.

- 6Datafolha, "44% dos evangélicos são ex-católicos" http://datafolha.folha.uol.com.br/opiniaopublica/2016/12/1845231-44-dos-evangelicos-sao-ex-catolicos.shtml December 28, 2016.