The story of the apparition of the Virgin of Guadalupe is one that almost any of her devotees can recount by heart: On December 9, 1531, only a decade after Spanish troops had conquered and supplanted the Aztec empire, a newly converted native Nahua man, Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin, was walking near a hill known as Tepeyac, on the outskirts of Mexico City. He was on his way to catechism classes when he heard beautiful sounds from atop the hill. Following the sound, he came upon a vision of a beautiful woman floating in the air. She told him, in Nahuatl, that she was the Mother of the true God, and that he should tell the bishop that she wanted a church built there in her honor. Juan Diego went to the bishop to do so, but was not granted an audience, so he returned to Tepeyac. She appeared again and asked him to return to the bishop. The bishop received him, but doubted the claims and asked for a sign. Juan Diego returned to Tepeyac, and the lady promised to send a sign the next day. Juan Diego was not actually able to return that day because his uncle fell gravely sick, but on December 12, he met her again. She reassured him and told him not to fear, describing herself as his mother, one who would care for him. She assured him that his uncle was cured, and told him to go to the hilltop and gather the flowers growing there to bring to the bishop. Though it was December, he found roses and other flowers growing there, and bundled the flowers in his tilma, or cloak, carrying them back to Bishop Zumárraga. When he unfurled the tilma, the image of the Virgin—the same image venerated above the altar at the basilica today—appeared to the bishop. When Juan Diego returned to his uncle, he learned that the Virgin had also appeared to the uncle, and had called herself by the name Guadalupe. According to tradition, a small chapel was built there almost immediately, and the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe was placed there.

Historians debate the historicity of the celebrated account, but her millions of devotees do not. The oldest written accounts of the apparition date to more than 100 years later.1 In a publication titled Image of the Virgin Mary, Mother of God of Guadalupe, Miraculously appeared in Mexico City, Fr. Miguel Sánchez described the events in 1648, citing oral traditions as sources.2 Fr. Luis Laso de la Vega described it the following year when he published a text in Nahuatl, the Nican Mopohua (“Here it is told”), which is the basis for the popular account described above.3

There seems to be something in the story to appeal to both native people and the Spaniards (and later criollos, Mexicans of Spanish origin): The site of the apparition is said to have been highly significant to native people. According to the oldest written account of Nahua life and cultural practice in pre-Christian times, jointly compiled by Nahua elders and a Franciscan missionary from 1549-1569, Tepeyac had long been a sacred place dedicated to an Aztec mother goddess. People came “from all the border regions of Mexico” to visit the sacred hill.4 Even after the site had been dedicated to Our Lady of Guadalupe, de Sahagún reports that native people and Franciscan preachers also called her Tonantzin, Nahuatl for “Our Precious Mother.” The name may have referenced the goddess previously worshipped there.5

The name Guadalupe also appeals to Spanish sensibilities, as a new world incarnation of a Spanish devotion. It references an older, large-scale devotion to a black Madonna, Our Lady of Guadalupe, centered at the monastery in Cáceres, Spain.6 The story of its appearance also fits another historic trope, applicable at Cáceres and elsewhere in Europe: “a peasant protagonist overcomes the skepticism of authorities to be vindicated by the prodigious powers of the newly discovered image.”7

The brown color of Juan Diego’s Virgin of Guadalupe is a key factor in indigenous Mexicans’ devotion and interpretation of the apparition, but interestingly, that too is in keeping with a long tradition in Spain of black images of the Virgin, including at Cáceres.8 Beyond their non-whiteness and shared name, though, the images of the two Virgins of Guadalupe are radically different, and difficult to conflate from a visual perspective.9

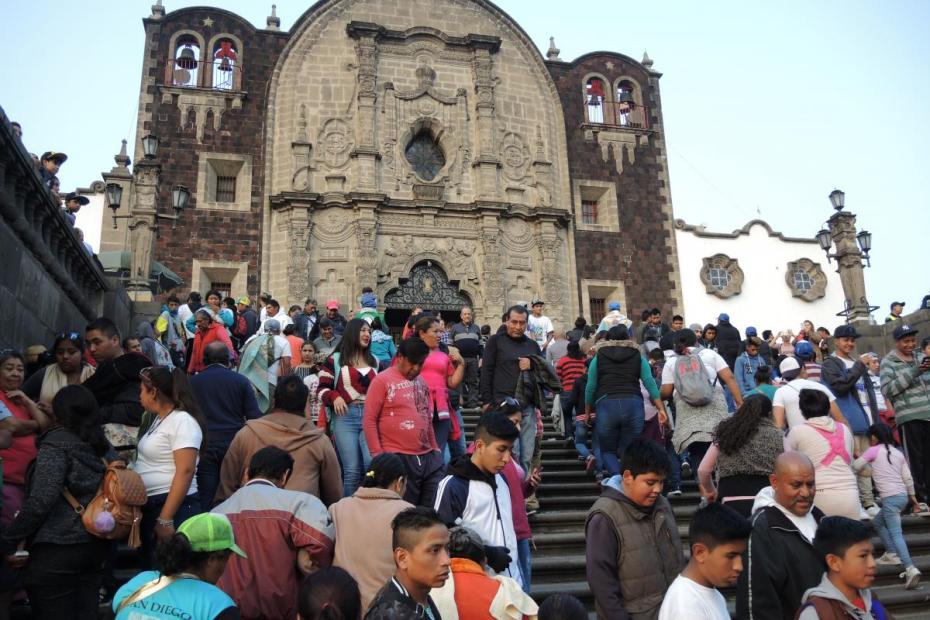

Successive shrines were erected on the base of Tepeyac, renamed Guadalupe, culminating in the still-extant old basilica (built 1695-1709) and the new, round basilica (built 1974-76). In 1737, in the face of a devastating epidemic, Our Lady of Guadalupe was proclaimed patroness of Mexico City. In 1754 Pope Benedict XIV declared her Patroness of all of New Spain, and declared December 12 to be her feast. In 1810, during the Mexican War for Independence from Spain, the image of Guadalupe was first used as a national political symbol, on the banners of the Mexican fighters.10 In 1921, the image famously survived intact when a bomb was placed below it. Juan Diego was canonized a saint in a ceremony led by Pope John Paul II at the basilica in 2002.

- 1For a full, more critical assessment of the origins of the famous account of the Guadalupe apparition to Juan Diego, including its complications from a historical point of view, see Stafford Poole, C.M., Our Lady of Guadalupe: The Origins and Sources of a Mexican National Symbol, 1531–1797 (University of Arizona, 1995). Poole, a Vincentian priest and historian, concludes starkly, “Guadalupe still remains the most powerful religious and national symbol in Mexico today. The symbolism, however, does not rest on any objective historical basis.” (225). Poole (82-99) reviews a variety of documentary references to devotion to the Virgin of Guadalupe at Tepeyec from the 1570s onward, but is careful to note that none mentions the celebrated story of the apparition and Juan Diego until 1649. The decision to canonize Juan Diego is based on a very different conclusion about that evidence, summarized by Fr. Eduardo Chávez in his book, Our Lady of Guadalupe and San Juan Deigo: the historical evidence trans. by Carmen Treviño and Veronica Montaño (Rowman and Littlefield, 2006). Timothy Matovina offers a shorter, but very helpful summary of the development of the devotion, and the conflicts over it, in Guadalupe and Her Faithful (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 2005), 1-12.

- 2Poole, 100-103.

- 3Poole, 100-126. The Nican Mopohua is one section of a larger work known as the Huey tlamahuiçoltica, parts of which seem to be compilations from earlier sources.

- 4Berhardino de Sahagún, in an appendix to the Florentine Codex (1569/1576), as cited in Jeanette Favrot Peterson, Visualizing Guadalupe: From Black Madonna to Queen of the Americas (Austin: University of Texas, 2014), 69. The Franciscan missionary lamented that devotion to the pre-Christian goddess continued there 50 years after the church had been erected on the hill.

- 5The use of that pre-Christian name, to help reconfigure indigenous dedication to her into dedication to the Virgin Mary, would have reflected a strategy that the Church had used in so many other settings since Roman times, building a new devotion over a prior, pagan one, but it worried de Sahagún, the Franciscan chronicler, that this was a pagan devotion in disguise: “everywhere there are many churches to Our Lady, and they [indigenous people] do not go to them. They come from distant lands to this Tonantzin, as they did in former times.” Poole, 78. Whether that worry is warranted or not, it suggests that devotion at the chapel dedicated to Our Lady there was widespread after 1531, though scholars debate the question. For a summary of scholarly debates on the origin and use of this term, see Peterson, 69-102.

- 6That same image, a triangular shaped, small statue, similarly is said to have appeared to a peasant in the fields. Language scholars often point out that the name Guadalupe is not one that could have arisen from the Nahuatl phonetic system.

- 7Peterson, 22. Also see Poole, 22-30.

- 8Peterson, 17-40.

- 9The Spanish image is black in complexion, bears a tiny Christ child in her arms, and is dressed in a triangular dress. The Mexican image is medium in complexion, standing in prayer, in a more flowing tunic. There is a “choir” image of her in Cáceres that bears greater similarity to the one in Mexico, but even these differences are notable. See Peterson, 129.

- 10Poole, 3. The uprising was led by a priest, Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla.