In a culture as religiously fertile and communal as in Nigeria’s Igboland, it should not be surprising that lay Catholic organizations flourish, even in a context where there is abundant clerical and religious leadership in the local church. The growth of the Church in Igboland has depended from the beginning—and still does depend—on the dedicated work of lay catechists. The development of lay Catholic organizations developed gradually, after the Church’s network of schools and other mission priorities were fully developed, often displacing or filling a void left by traditional forms of religious association. Religion is a way of life here, not something for an hour on Sunday. Catholic organizations clearly provide welcome additional channels of expression for faith.

At Hearts of Jesus and Mary Parish, a relatively small parish by Enugu standards, less than a decade old and working to launch its two mission stations into independent parishes, there is an abundance of lay organizations: Parish Council, Block Rosary group, zonal base communities, Legion of Mary, Catholic Women’s Organization, Catholic Men’s Organization, Altar Boys’ (still all boys) Association, choir, and Catholic Charismatic Renewal among them. A good deal of the charitable work done in the parish is enabled by and through the lay groups. Members of organizations like the Knights of Saint Mulumba and the Ladies of Saint Mulumba, Knights of Saint John, and Confraternity of Our Mother of Perpetual Help have been instrumental in building up the parish.1 Children come together for catechism for an hour and a half weekly. Many also participate as Junior Legion members, in Block Rosary, and in other forms of common prayer.

The lay groups in the parish prize being highly organized, with officers and meetings and plans for moving forward. The charismatics, for example, are approved and operate under the oversight of a diocesan committee. Legion of Mary groups, Block Rosary, etc., gather at the diocesan level. Little happens outside the oversight of, or at least without careful deference to, the clergy, but all of these groups are lay-led.

The many organizational titles and roles in these organizations are said to fill another function: by all accounts, Igbo people are highly achievement and status-oriented. Kingly, chiefly and other titles prominent in traditional society continue to garner tremendous social respect. Access to those roles always required that men merit, not inherit, them. An array of religious, academic, professional and other titles are constantly referenced as yardsticks for achievement and status. Priests are not simply Father, but “Reverend Father,” Sisters are “Reverend Sister.” Even “Seminarian” is a title. Laypeople are often quick to note who is the president, or secretary, or treasurer of an organization, or a program lists a person with “KSM” (Knights of St. Malumba) after his name. While membership in organizations is on the decline in many Western countries, Igbo society seems to have added a whole new layer of organizational opportunity. In such a communitarian society, associating in lay Catholic organizations gives members the chance to mark the ways they have excelled and to take on the “reflected prestige from the glory of belonging to a particular group.”2

Some organizations that remain influential today, like the Legion of Mary (founded in 1933) and the Knights of St. Malumba (1953), were founded by clergy. But it was the devastation of the Nigerian Civil War, perhaps even more than the reforms of Vatican II, that provided an opening for many of the most significant lay organizations in Igboland today, almost all of which were also lay-founded. Because the war resulted in the expulsion of foreign missionaries, “there were insufficient personnel for ministry, and thus the role of the laity in evangelization—reinforced by the Second Vatican Council’s larger lay presence in such work—was given serious attention.”3 Laypeople were in the vanguard of rebuilding, even as seminaries blossomed again.4 The war also opened up greater room for women’s leadership, and women took the opportunity with new vigor.5

Block Rosary Crusade

The Block Rosary Crusade, led by laypeople in parishes and mission stations, flourishes in many parishes, including Hearts of Jesus and Mary. Its success and status as an indigenous Igbo movement bears highlighting. Its origins seem to date back to just before the civil war of 1967-70, and participation spread significantly in its aftermath.6 “In Onitsha [a city about 2 hours south of Enugu] where the movement is now very widespread, the origin is attributed to the association of storeboys (shop-keepers) who also guarded their masters’ stores and shops at night in and around the marketplaces. At night, these boys began the practice of meeting in front of one shop or another… where they organized group night prayers as well as kept one another company in the night.” The war disrupted these activities, but after the war “such prayers were begun to be reorganized in wards or groups of adjacent streets and houses. They were called a Block Rosary… Being said nearer residential areas it became possible for more people, especially children, to join the prayers” and the movement grew. “What is certain about its origin… is that it did not arise from any special direction or inspiration of the clergy… it has remained to this day a largely non-clerical movement.”7 Ogbu Kalu describes its flowering in the aftermath of the war as a sign that Igbo people were ready to fully internalize the faith as their own, further than had been the case before.8 At Block Rosaries, children—two girls and one boy, standing in for Lucy, Jacinta and Francis, the children to whom Fatima was revealed—lead the others in praying the Rosary.9 In the Holy Spirit mission station, they gather every Wednesday evening at 5 p.m. and do some sharing, and learn lessons from each other about how to be good children. One adult told me that it is an especially important organization because “the prayers of children have special power. So they are called to pray together.”

The Legion of Mary

The Legion of Mary is a small group, but a dedicated one. On Wednesday evenings at Holy Spirit mission station, they meet for prayer near where the children pray the Block Rosary in the late afternoon. They visit people in their homes to talk about Christ, to visit the sick, and to help the pastor know about the needs of people. They say that there are many people in the neighborhood whose faith is not strong, and that they want to help them to grow stronger. They want all the people to know and to share “the virtues of Mary. She teaches us how to be humble, how to be obedient, how to be in service to others.”

Zonal base communities

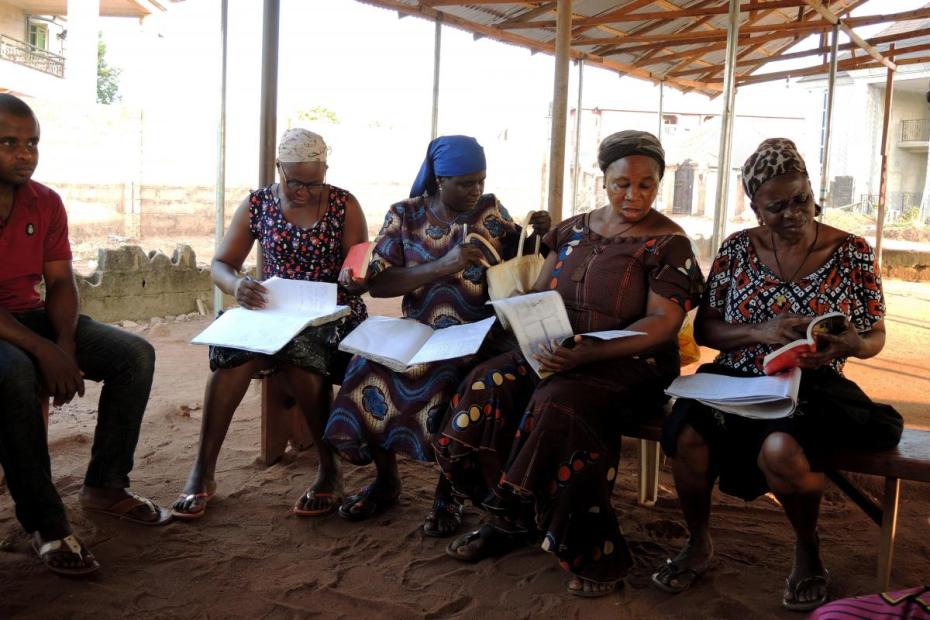

Men’s and women’s groups, and lay zonal base communities also meet regularly for prayer, sharing, fundraising and good works. In December, 2019, for example, the zonal base community at Holy Spirit mission station gathered for a “love feast,” a banquet where the members bring whatever food they can as an offering to the others, and sit in a circle and share. “Sharing” is the theme of the group, one said: “If you give out generously you will receive back.” Their prayers were to remember those who died that year, and to pray for safety during the upcoming “crucial period,” when about two-thirds of the group travels to home villages to be with their families for Christmas, which carries risk on the roads in between. Normally, they meet on Wednesdays for a prayer meeting, to study, or for a spiritual talk from one of their members.

The Knights of Saint Mulumba

Several parish leaders and leaders in the charismatic movement belong to the Order of the Knights of Saint Malumba (KSM), a Nigerian Catholic fraternal organization. Founded in 1953 by Fr. Anselm Ojefua, its aim was to provide an alternative to membership in traditional Igbo secret societies, whose religious practices were seen as antithetical with Catholicism, and as an alternative to more contemporary groups like the freemasons.10 V. Nwosu suggests that the success of the Knights derived, and still derives, from “the fact that it gave lay Catholics a special status in the church which was denied them in traditional society since traditional title-taking was still forbidden to Catholics, although that ban has now been lifted in many towns.”11

An order of women, the Ladies of Saint Mulumba (LSM) was founded in 1978. Together, the Knights and Ladies claim a membership of more than 23,500, mostly from the business and professional classes, with slightly more women than men. That membership is small, compared to the population of Igboland, but at least in Enugu they seem to be influential as church leaders and supporters. Like the Knights of Columbus in the USA, on special occasions the Knights of Saint Malumba wear colorful capes, plumed hats and ceremonial swords. Like the Americans they also have an insurance program for their members.12

Catholic Charismatic Renewal

One of the growing, and more visible groups at the Hearts of Jesus and Mary parish is the charismatic prayer group, which was officially commissioned by the diocesan leaders as a full member of Catholic Charismatic Renewal, “to spread the full message of Christ” in 2019. Even charismatic prayer groups do not rise up entirely spontaneously in Enugu. In this parish, full recognition followed six years of organization before it was recognized as the God’s Temple prayer group. It is almost as old as the parish mission itself, having been founded in 2013 as an outreach of the Dove of Peace prayer group at Holy Cross Parish, the parent parish of Hearts of Jesus and Mary Parish. That parish’s charismatic prayer group guided them in the process towards official status. They are well organized, not only with leaders, secretaries, treasurers, but also ministries for singers, stewardship, praise and worship, teaching, service team, evangelization, and children’s formation. Every member belongs to one of those ministries.

The God’s Temple Prayer Group meets at the parish church three times a week: for a prayer meeting on Monday evening, an administrative meeting and children’s meeting on Tuesday evening, and a bible study on Thursday evenings. They also visit parishioners in their homes. The prayer group meeting, pictured in the video here, begins in a decidedly uncharismatic way, with the recitation of the Rosary. It includes more songs to Jesus in an Igbo-derived musical style. The format shifts between messages of intense devotion to Jesus, and occasional questions, “Are you happy?” The style is vigorous, though much less so than at events like Fr. Mbaka’s Adoration Ministry or similar, more Pentecostal-style ministries.

Other parishioners, including those who favor more quiet prayer, are described as being largely welcoming to the charismatics, though they report that there are still members of the parish who don’t understand what they do and say things about them. In the early years of the movement, they said, priests were suspicious, but overwhelmingly now they say that priests of the diocese welcome and support it.

The prayer group reaches out to bring unchurched or other-churched people into the movement, but reports that new members are typically already Catholic churchgoers. At the Monday night praise and worship meetings there were about three times as many women as men, including a half dozen pregnant women or women or carrying young babies. Husbands, one member reports, are sometimes impatient with the movement because they “don’t like that their wives are out so many evenings.” But as is true in many other organizations, the prayer group provides an opportunity for women to lead. In this case, the leader is a lay woman called Sister Georgina Eneh.

In one sense, the charisma in “charismatic” is watched carefully: prayer group members are careful to point out how much they depend on the parish priest, and to emphasize being/remaining faithful to the Church, not least because it has been the case that members of some Catholic charismatic communities have gotten trained and then left to form their own churches.

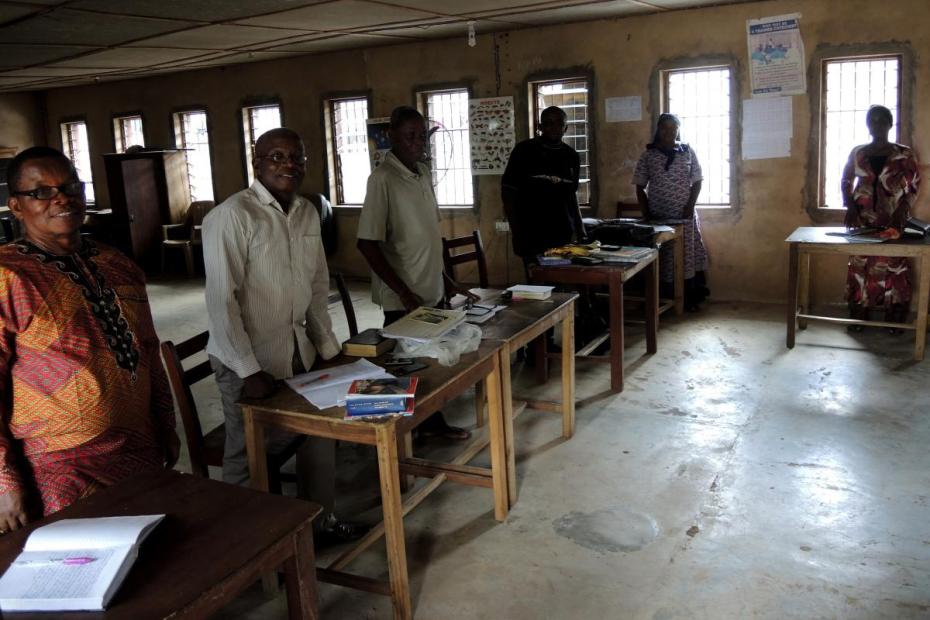

Lay catechists

The position of the lay catechist is deeply entrenched in the life of the parish or mission station. In the first half-century or more of Church presence, lay catechists were instrumental in evangelizing the peoples of Igboland, when clergy were few and possessed limited understanding of local cultures.13 Even today, despite the robust number of priests, sisters and seminarians in Igboland, parishes, and especially mission stations, often depend on them. Catechists are recognized as official teachers in the community, members of the “council of catechists,” and are called and trained by the diocese. Both men and women serve in the role today. Coordination of catechism classes for children is a primary responsibility, but many also handle a good deal of marriage preparation.

One catechist, a married father of four relatively young children, told me that it was the inspiration of the Holy Spirit that called him; “desire to work for God kept disturbing me.” The work is “both social and spiritual… the spiritual is number one, but if you don’t know the social aspect of it, if you don’t know how to live... you can’t lead in the spiritual.” He visits people in their homes, including the sick, and calls on the priest to bring communion when appropriate. “I am the bridge between the Church and the priests. If there is a dispute or a conflict in the family, I help out. If it is beyond my control, then the priest comes in.” Families come to ask for his help. Making peace is important in the parish or mission. “We don’t want problems to be prolonged.” Mostly, he’s learned, “you hear more, and talk less. You don’t [succeed by trying to just] correct people’s problems.” Often the problems derive from lack of money to care adequately for the family. Most of these problems are ordinary. When it comes to “spiritual problems,” he leaves those to the priests. igbo

- 1This article is based primarily on research in Enugu, with ventures up to Nsukka, over the course of 11 days in December 2019. Thanks to Fr. Paulinus Ike Ogara for his patient guidance and insight on the ground, and to Fr. Theophilus Enebechi, catechist Odoh Basil A., and the people of Hearts of Jesus and Mary Parish and its mission stations for their warm hospitality.

- 2Frank A. Salamone, “Continuity of Igbo Values after Conversion: A Study in Purity and Prestige,” Missiology 3, no. 1 (January 1975): 33–43.

- 3Jacinta Chiamaka Nwaka, “The Catholic Church, the Nigerian Civil War, and the Beginning of Organized Lay Apostolate Groups Among the Igbos of Southeastern Nigeria,” The Catholic Historical Review 99, no. 1 (January 2013): 78-95.

- 4V. Nwosu, The Laity and the Growth of the Catholic Church in Nigeria: The Onitsha Story 1905-1983 (Onitsha: Africana—FEP Publishers, 1990), 117-143, and Jacinta Chiamaka Nwaka, “The Catholic Church, the Nigerian Civil War,” 78-95

- 5Nwosu, The Laity and the Growth of the Catholic Church in Nigeria, 128-133.

- 6Ogbu U. Kalu, The Embattled Gods: Christianization of Igboland, 1841-1991 (Trenton & Asmara: Africa World Press, 2003), 203.

- 7Nwosu, The Laity and the Growth of the Catholic Church in Nigeria, 133-4.

- 8 Kalu,The Embattled Gods, 205.

- 9Writing about Onitsha in 1990, Nwosu (135) describes a number of monthly gatherings in the parish and parents’ events surrounding the Block Rosary, but I was not witness to these in Enugu.

- 10Nwosu, The Laity and the Growth of the Catholic Church in Nigeria, 76-77.

- 11Nwosu, The Laity and the Growth of the Catholic Church in Nigeria, 77.

- 12Though the insurance program was developed later, the Knights’ website indicates that their founder took the Knights of Columbus as a model for their own organization.

- 13It is important to remember, too, that this was an era when few Igbo men and women were welcomed into the priesthood or religious communities. “Roman Catholics continued to depend more on the indigenous people and yet kept them from the priesthood.” In 1950, fewer than 20% of clergy in the region were Africans. (Kalu, The Embattled Gods, 99). The numbers seem particularly striking when contrasted to the huge number of Igbo men and women in the priesthood, seminaries and religious life after 1970.