Israel is an especially compelling and complicated context for the Catholics who live there. Because Christianity and Judaism share a common origin; because this is the land where the central events of Christian revelation took place; because of the sacred status of Israel to Jews as the Promised Land; because of the often fraught relationship between Christians and Jews through history, especially the role that Christians played in the Holocaust; because Christian (and Muslim) Palestinian families held parts of this land as their own for millennia before Zionism emerged and triumphed; because of Israel’s mission to be a Jewish homeland; and because Jewish culture sets the tone for daily life, Israeli Catholics regularly encounter points of deep connection and incongruity. Even as Israel is the setting for dedicated and intentional Catholic communities, the children of those faithful tend in significant numbers to assimilate into the larger Jewish culture.

Founded in 1948 as a restored homeland for the Jewish people and a refuge from persecution, and shaped by waves of Jewish immigration from diverse cultures, Israel is organized under a constitution that guarantees freedom of religion but is also designed to ensure the country’s status as a Jewish state. Precisely what it means to be Jewish — whether that designation necessarily entails religious observance, or need only be a matter of identity, family and culture — is contested, but for Jews along the spectrum from Orthodox to secular, the Jewishness of Israel, and the necessity of ensuring the country’s Jewishness into the future, is taken for granted, even as Israel’s security is not.

Religious observance in Jerusalem tends to be strict, and Orthodox Jewish leaders tend to play a more significant role there, but cities like Tel Aviv and Haifa are quite secular or only loosely observant. Even in secular communities, Jewish culture is socially normative.

In the course of the many Arab-Israeli conflicts since 1948, the number of Catholics here has declined as people lost their land and were exiled, migrated or fled Israeli territory. Still, small populations of Palestinian Catholics and other Christians continue to reside in Israel proper and in the Israeli-controlled West Bank Territories, from Jerusalem up through Galilee.1

Though many readers may be aware of a pattern of Christian out-migration since 1948, it may be surprising to note that the same years also witnessed a smaller, deliberate migration into Israel by Catholics who were drawn in different ways to the national project of building a Jewish homeland, and who became citizens of Israel. These Catholics formed their own Hebrew-speaking Catholic community that continues to the present day. More recently, a significant number of Catholics are among those who have come to Israel as temporary laborers or as refugees, very few of whom can ever likely become citizens. Each of these groups — Palestinian Arab, Hebrew speaking, and migrant/refugee — represents a somewhat distinct community within the Latin Church.

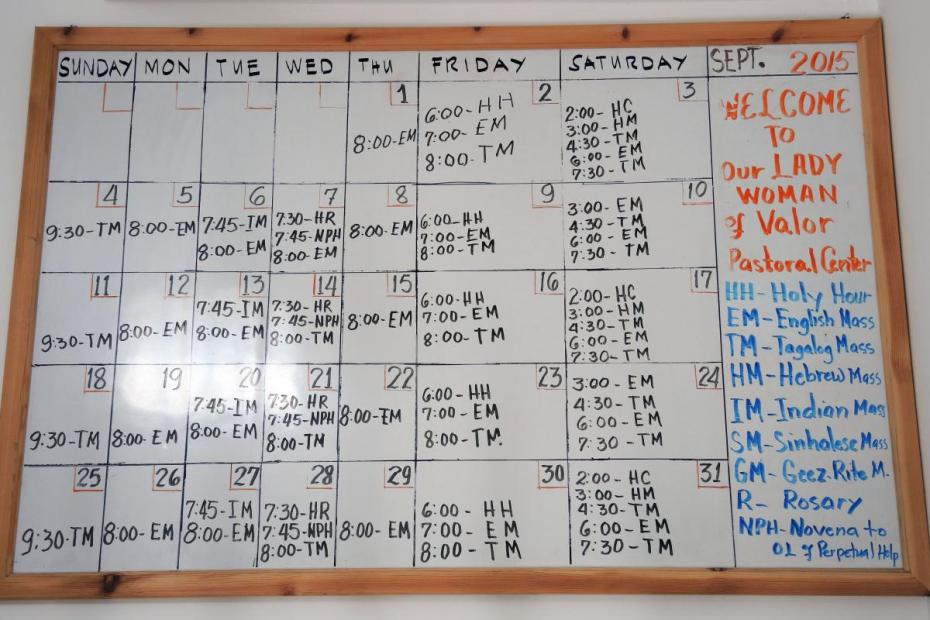

For a Jewish country, Israel has a significant number of Catholic clergy and Religious. Because this is the land of Jesus’ birth, ministry and Passion, religious orders have a large presence in Bethlehem and Jerusalem, and Christian pilgrims often travel here. In the Christian quarter of Jerusalem’s old city, and in a number of places nearby, Armenian, Latin, Maronite, Melkite and Syriac Catholic churches and religious houses are cheek by jowl with Orthodox churches and monasteries. Three patriarchs — two Orthodox and one Latin Catholic — are headquartered there.

Lay Catholics in Israel live in somewhat distinctive, but overlapping communities in Eastern and Latin churches. Indeed, evidence from conversations with lay Catholics, confirmed by some clergy, suggests that ecclesiastical boundaries, including Catholic-Orthodox boundaries, are typically far more relevant to clergy than to the laity.2 Fr. David Neuhaus, SJ, former Vicar for Hebrew-speaking Catholics, estimated the following in 2021: "In Israel there are four groups of Christians: Palestinian Arabs who are citizens of Israel (120,000 people); Hebrew-speaking Christians who are sociologically part of Jewish society (40,000); migrant Christians who are without permanent status (150,000); and expatriate Christians who serve the Church (1,000)."3

Though ecclesiastical distinctions tend to be less important, socio-cultural and political differences foster other kinds of boundaries between the Arab, Hebrew-speaking, and refugee communities. Arab Christians are more likely to resist the control of a Jewish state over lands they regard as their own. The Hebrew-speaking Catholic community, founded in significant part as a counter-witness to anti-Semitism, values a Jewish state and worships in Hebrew, not Arabic. The newer immigrant and refugee communities often prefer to worship in their native languages and may not be especially fluent in Hebrew, but their children tend to be fluent in Hebrew and not speak their parents’ language well, if at all. For the Hebrew-speaking Catholic community, given its commitments, it is a challenge to think about how to welcome people of the world who come here and bring their own cultures, and to be faithful to its original mission to be a church that deliberately grounded in the Jewish context.

Catholics & Cultures entries on Israel currently focus on the Hebrew-speaking Catholic community, and, to a lesser degree, the migrant communities who comprise the majority of Latin rite Catholics in Israel. Palestinian Arab Catholics, whether Latin, Melkite, or Maronite, will be covered in future articles. The Hebrew-speaking Catholic community provides a fascinating connection to the Jewish origins of the faith and is deeply embedded in contemporary Jewish life. If the weight of history makes the Arab- and Hebrew-speaking communities particularly interesting, the weight of numbers, among other factors, makes the newer migrant and refugee communities important. These communities have rapidly expanded the number of Catholics in the Holy Land for the first time in a century, but they have a quite tenuous position in that society.

- 1Though not yet described in depth on the Catholics & Cultures site, Christians living in the Palestinian Territories will be represented on a distinct page, under "Palestinian Territories."

- 2The entries for Israel are based on interviews with lay Catholics and clergy in Tel Aviv and Jaffa, Jerusalem and Beer Sheba in October 2015. The author especially thanks Fr. David Neuhaus, S.J., who served then as Patriarchal Vicar for Hebrew-speaking Catholics, for his generosity and assistance opening doors in these communities.

- 3 Nicholas Frankovich, "Arab Christians in the Holy Land: a conversation with David Neuhaus, SJ," Commonweal October 2021, v.148 n.9 p. 42).