Migration is an extraordinarily important theme of Irish life, from even before the massive flight during the Irish Potato Famine (1845-1852). A country unable to support families on poor and limited land sent family members all over the world, holding “wakes” for those who left on the assumption that they never would be seen by family again. Huge cohorts of Irish nuns and priests similarly went out to the world for generations as missionaries. Outward migration continued through the 1970s, and still continues to a lesser degree, but a new phenomenon has overshadowed it and begun to change the country.

The huge outward migration pattern reversed itself during the Celtic tiger period 1995-2008. Ireland’s economy expanded at an extraordinary pace as corporations move to Ireland to take advantage of a well-educated, English speaking population and a country that served as a bridge to the European Union. The boom, though it proved illusory, changed Ireland’s self consciousness radically, as it shifted from being a place people needed for generations to move away, into a place where the possibilities seemed unlimited.

During this period when Ireland witnessed a large decline in church attendance, it also saw this influx of workers from other parts of Europe, Africa, India and the Philippines. In 2013, according to the Pew Research Center, 740,000 people—more than 16% of the population—was born outside of Ireland.1 Ireland is even home to a Muslim population of about 50,000. Ireland has become a much more globalized society than in the past. Notably, too, the migration has begun to shift Ireland’s self-conception of who and what is Irish.

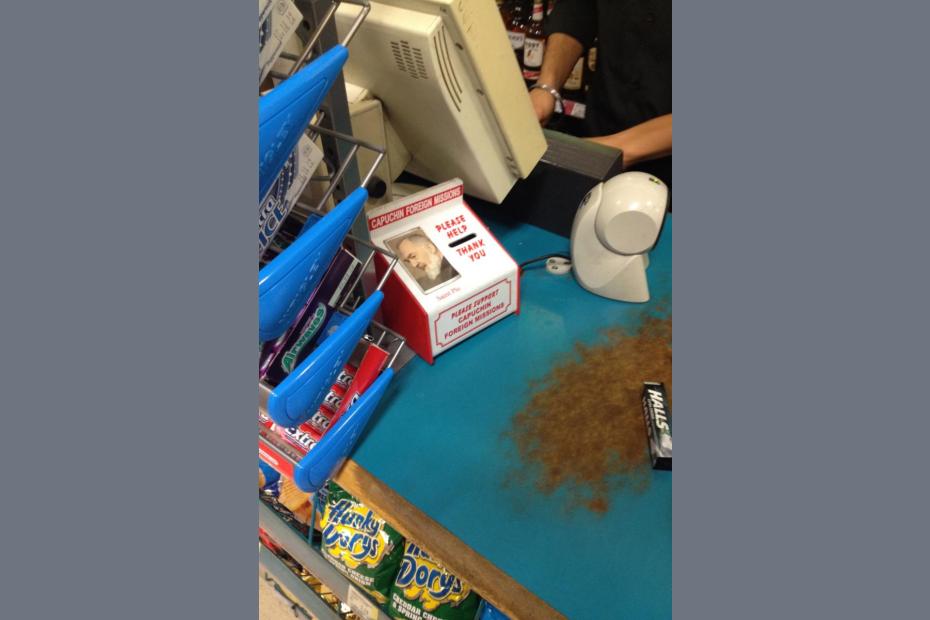

To some degree, the migration brought new religious energy to some parts of Ireland. The Archdiocese of Dublin offers chaplaincies and regular Masses to Catholics from 15 different national groups. Poles have their own thriving parish in Dublin, the grand St. Adouen Church, which was said to have drawn, at its peak during the boom years, up to 5,000 people to Mass a week. One hundred other towns in Ireland offered a weekly Polish Mass.2 As one Dublin priest reported, “If I didn’t have the Poles in my pews on Sundays, I’m not sure who I’d be preaching to.”

A small proportion of Irish Catholics oppose such migration. The numbers increased as migration increased, and even more after the economic collapse, but remains low. According to the 2009 European Social Survey, 14.9% of Irish Catholics believe that immigration from “poorer countries outside of Europe” should stop, and 10.3% agreed that immigration of persons “of the same ethnic group as the majority” (i.e. foreign-born ethnic Irish) should stop.3

- 1Pew offers a graphic that allows readers to see where Ireland’s migrants came from, at http://www.pewglobal.org/2014/09/02/global-migrant-stocks/

- 2Newest Arrivals Enlighten Global Catholicism, accessed at http://www.nbcnews.com/id/23636536/ns/world_news-europe/t/newest-arrivals-enliven-irish-catholicism/#.VNEx3lVg738

- 3Data are aggregated in the report by Eoin O’Mahony to the Irish Catholic Bishops’ Conference, “Practice and Belief among Catholics in the Republic of Ireland: A summary of data from the European Social Survey Round 4 (2009/10) and the International Social Science Programme Religion III (2008/9)” 24.