Whereas many aspects of Catholic attachment and practice are declining in Ireland, no aspect of Catholic practice seems as vital as the Irish wake and funeral. Whatever their degree of attachment to the institutional Church, for the Irish, a funeral can be an important social event. In interviews, it was surprising how many Irish referred to some instance of “a good funeral.”

In many secularized countries, of course, baptism, marriage and funerals remain part of people’s lives even for those who are loosely attached to the Church. But what these Irish interviewees referred to was not simply a quiet but formulaic ritual, a safe requirement before one meets one’s maker. Rather, it spoke to a deep and important Irish Catholic sense of ritual that endures, even if it has changed in some ways over time and is deeply complicated by crises of belief. Wakes and funerals readily bring out even those persons who do not otherwise go to church anymore, for an occasion when people participate fully.

The qualities of Irish wakes and funerals, as a whole, are much different than any other culture. A wake is an occasion for viewing and perhaps touching the body, embalmed, dressed in Sunday best and visible in an open coffin, as well as for mixing with the family, expressing sympathy, recalling memories about the deceased. A wake, at least when the person has lived to what most people consider a full age, can include laughing, jokes, even singing and a drink alongside real grief. Following a wake, the coffin is then typically brought to the church and spends the night there in front of the altar, awaiting the arrival of mourners the next morning for the funeral Mass.

At funerals, many families want to see a good deal of “personalization” mixed in to the funeral, so that it represents something about the deceased, rather than repeats theological certainties about death and resurrection. A funeral might even include some of the favorite songs of the deceased, though the Church discourages this.

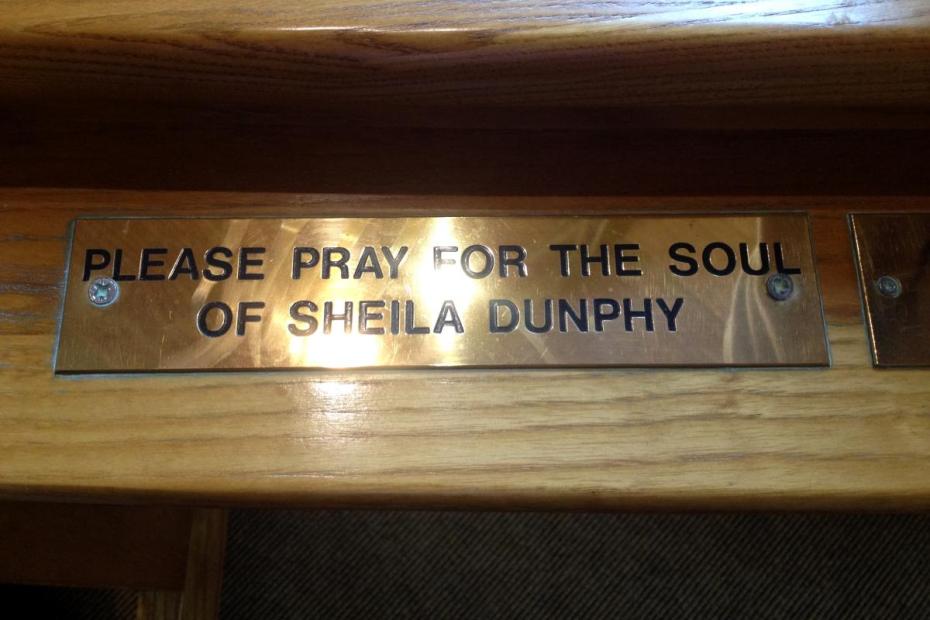

After the funeral and burial, out-of-towners, close friends and family are invited to lunch, an event that marks a clear transition back to ordinary life, while gathering loved ones together. The dead are remembered at anniversary masses paid for by stipends from friends and loved ones.

Beliefs about the afterlife have certainly become more complicated. In surveys, slightly more than 83% of Catholics in Ireland “definitely” or “probably” believe in life after death, slightly more than 87% “definitely” or “probably” believe in heaven, 58% in hell, 71% in miracles. But as is true in many other globalized societies, Catholics also expressed belief in non-Catholic beliefs. Almost 32% “definitely” or “probably” believe in reincarnation, and almost 27% in nirvana.1

- 1Data are aggregated in the report by Eoin O’Mahony to the Irish Catholic Bishops’ Conference, “Practice and Belief among Catholics in the Republic of Ireland: A summary of data from the European Social Survey Round 4 (2009/10) and the International Social Science Programme Religion III (2008/9).”