Note: This page was originally published in different form, based on research conducted in Veli and Thumba in 2014. In 2020, following the publication of outstanding long-term, in-depth research by Kerala native P.T. Mathew, S.J. on the beliefs and practices of the Catholic fishing community in Vizhinjam, just 20 km down the coast, it has been revised in its entirety, in consultation with Fr. Mathew.

Southern Kerala’s seaside villages, whose location shaped livelihoods and made them points of contact centuries ago between Indians and seafaring Christians and Muslims, are home to many communities of Latin-rite Catholics. Villages near the southern tip of India like Veli, Thumba, Vettucaud and Vizhinjam—sources of the account that follows—are places where Christian heritage, the Indic religio-cultural context, and a life of dependence on the sea shape a vital and complex form of Catholic practice.

Whereas a good many Catholics in the state of Kerala belong to the Syro-Malabar and Syro-Malankara churches descended from the ancient Thomas Christians of India, Catholics here are mostly Latin rite, their ancestors having converted beginning with the missionary visits in the era of St. Francis Xavier in the 1540s.1 Residents in Veli occasionally share their pride that St. Francis Xavier had walked and preached along these very beaches.

Their occupation as fishermen had relegated them beneath the caste hierarchy, which may have contributed to their conversion to Catholicism, to a faith that would supposedly render caste irrelevant. Such status is difficult to shake off, though. The Catholics at Vizhinjam, for example, are conscious of their identity as members of a caste-like group, Mukkuvars, in a context where caste and religion have long been essential determinants of identity, marriage prospects, and many other aspects of life. Not all fishermen in the region are Catholic, and Vizhinjam is a much more diverse and larger town than Veli and Thumba, but fishing in this region is a predominantly Catholic profession today.2

A casual visitor to Veli and Thumba would be immediately struck by the number of Catholic churches that are along the coastal road—one every kilometer or two—along with many shrines, Catholic schools and clinics. The towns are divided into small residential neighborhoods or units, each named after a saint. The vitality of Catholic life there is palpable. Many families pray together at home daily, and Catholic images are prominently displayed in homes.

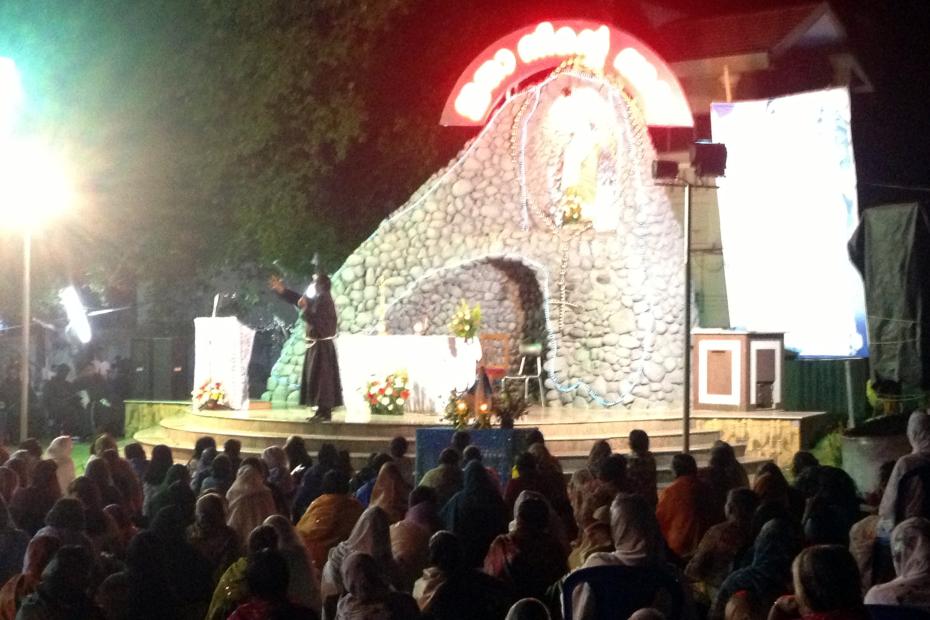

Religion is an all-encompassing part of life here, but most of the parish-centered religious life in these towns takes place in the dark hours, before and after the heat of day. The early morning is punctuated not only by the sound of roosters, but also the sound of singing from various churches. Mass attendance is strong. A trip down the coastal road on a single night saw a crowd gathered at one church for the feast of St. Anthony, a packed Mass at another parish, hundreds of parishioners in front of another church listening to novena preaching, and a line of people at a giant Christ the King statue in front of another.

A world more complex

Fishing is not the only source of livelihood here, as we shall discuss later, but fishing has long been the foundation of the economy. Some men fish relatively close to shore, on short-term trips to sea, while others venture farther out for much longer. Fishing is a male-only occupation, but women work in allied occupations selling fish and keeping up the homes that men return to. The dynamics of fishing life are inherently different from the dynamics of agricultural or urban life.

While fishing is a male-only occupation, women work in allied occupations such as selling the fish at market.

For people here, the sea is a source of bounty and sustenance, but it is also mysterious, fickle and sometimes deadly. Mukkavar people speak of the ocean as a mother, an “eternal provider” in whom they have “unfailing faith.”3 She must be revered, but at times she also must be struggled with, and never taken for granted. Elders, Mathew reports, advise, “Never go fishing with the assurance that you will get back safe.”4 “Our life is a life-long wrestle with the ocean,” one man tells him.

“Wrestling, fighting, and struggle are words that recur in their dialogue. There seems to be an irresistible urge for religious symbols and expressions that are attuned to a militant mindset.”5

P.T. Mathew’s extended engagement with the Catholic fishermen at Vizhinjam offers insight into practices and beliefs not so apparent, sometimes even hidden. These fishermen rely on folk wisdom accrued across generations to “read” or interpret the sea, including its colors, currents and movements—necessary skills to find a catch, navigate, and ensure safety from storms. They also rely on scientific forecasts from the Indian Meteorological Department. No less, they believe that supernatural forces determine their fate. These can sometimes be read through omens, manipulated or held in check. Seemingly ordinary occurrences on the fisherman’s path to his boat—the actions of a cat, the presence of an empty pot—are regarded bad omens. Certain actions by women near the beach can easily anger Mother ocean, but can be regulated: women are therefore not allowed on a fishing boat, except on Christmas day.6

Adherence to rituals and taboos—some Christian, some not, many a mixture—can alleviate danger. A priest’s blessing is part of the ritual to launch of a new boat, as is the traditionally Hindu custom of breaking open a coconut. En route to their boats, “[b]oatmen pause and pay homage to their Amma [Mother] (Cintāthira Māta), the patroness of the church.”7 When heading out to sea, a fisherman who wore a turban would always remove it, a traditional local act of homage, and wrap it around his waist, because “Kadalamma (Mother Ocean) does not like that... She will push the boat back in fury if we fail to do that.”8 Prayers to St. Anthony garner protection from big fish, and bad luck can be avoided by not uttering the name of a type of fish before trying to catch it.9

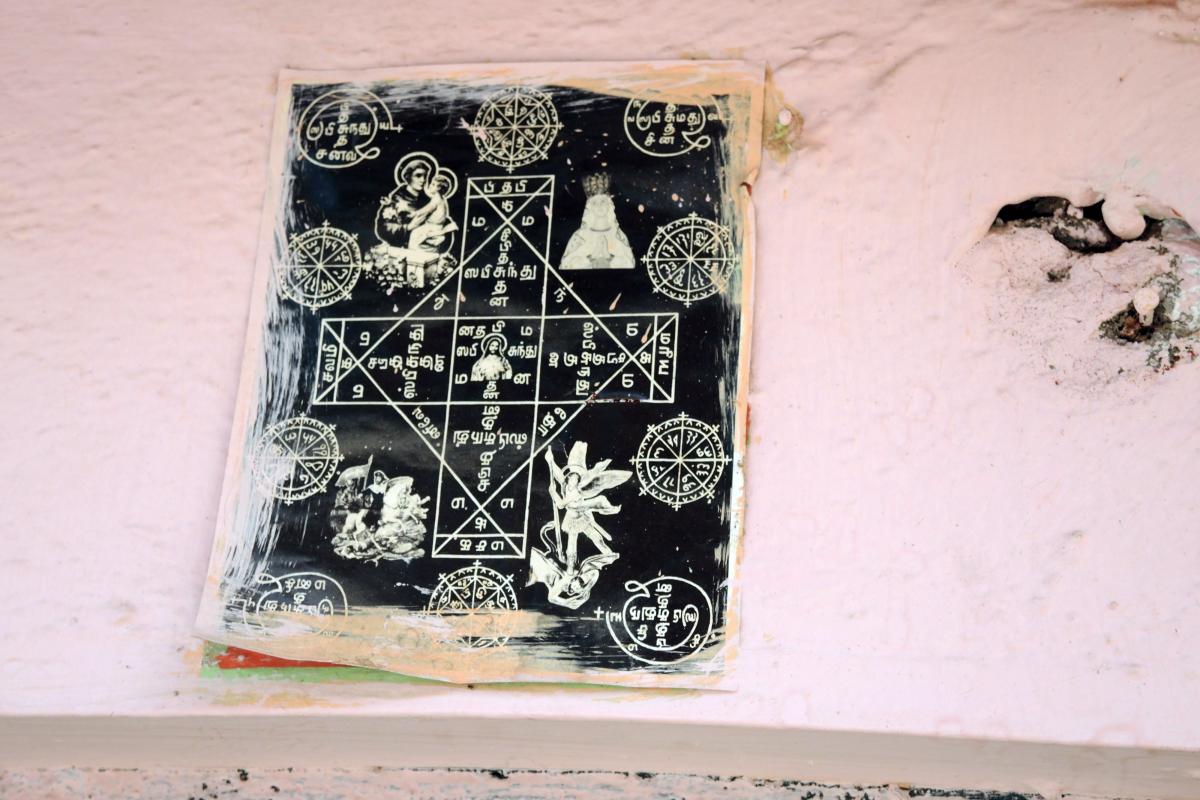

Fishermen seek to protect themselves not only against dangers at sea, but against threats born from human malice, when humans harness evil supernatural powers, including through the “evil eye,” to cause harm. Fishermen often believe that bad events in their lives were caused by curses put upon them by enemies, “although nobody would admit” to practicing ritual acts to cause misfortune for others.10 Though disapproved by the Church, mystical rituals known as mantravādam have a hidden place in Catholic fishing communities to ward off evil spirits or to undo the misfortune cursed upon them. The origin of these practices is in Hindu religion, but Catholic fishermen practice them as well, in largely Christianized fashion, or not. They do so by employing amulets on their boats or gear to bring good luck or to ward off misfortune and evil, or by placing a Christianized version of a yantra over the door of their homes. Some practitioners might recite the mantras, naming Hindu gods and/or Christian saints like Antony, Michael and Sebastian who are believed to have the power to overcome evil. For others, the images are too mystical to decipher, but their power does not depend on the bearer’s understanding.

A Christian version of a Yantra, a mystical image for meditation, or used a protective amulet at the entry to a house. This one is in Bangalore, but they appear at Kerala fishermen's homes too. The sacred heart is at the center of a cross, surrounded by St. Antony, the Virgin, St. Michael, and St. James, to ward off evil from all directions. The letters of the mantras, in Tamil, are meant to symbolize meanings beyond ordinary comprehension.

One form of mantravādam, the “Antoniār chit,” entails inscribing a mantra on a small copper plate, “placed before the image of St. Antony and prayed upon for 13 successive days,”11 after which it might be tied to a fishing net to ensure a catch (“the divinities are invoked… to lead all fish into the net of the devotee and protect the net”), kept at home to ward off evil spirits, or even rolled and worn on the body. One interviewee reported that St. Antony is especially powerful because he “performed 13 miracles (puthuma) while Christ has only 12 to his credit; the 13th one is especially for helping us, the fisherfolk.”12

All such practices take place alongside, not in lieu of, intensive adherence to Catholic sacraments and devotions. The rationale is additive. The ritual patterns and aesthetic of mantravādam are often Indic, while the saints appealed to are Christian. In the multilayered Indian religious context, Catholics might also make offerings at Hindu shrines and at mosques as well, and Hindus and Muslims could do the same at Catholic ones.13

Local inflection in conventional devotion

In the coastal villages, practices that seem to be more conventionally Catholic also take on localized meanings, forms and nuances.

In Vizhinjam, devotion to Cintāthira Māta, the Lady of Good Voyage, protector and refuge of seafarers, has a primary place in seafaring Catholics’ lives, and in the main churches. She is portrayed above the altar holding a ship, literally as a kappalkkāri, a ship-bearer. “When a fisherman is reported missing in the sea, or when a calamity occurs in the village, women and children rush to the statue and the old church and cry aloud in frenzy, ‘You come down, Amma! You come with your son and save us!”14 Her feast is celebrated there for nine days in January. In addition to typical Indian Catholic rituals like a flag raising, daily prayers, dressing Mary in new saris and leaving peppercorns and salt at the base of a statue, devotees might present her with a silver boat.15

In all these communities’ parishes, feasts are as important as anywhere else in India, which is to say, tremendously important. Madre de Deus Church in Vettucaud holds its major feast, the 10-day Christ the King pilgrimage in November. This video shows the remarkable scale and pageantry of the feast. The festival also holds an important social role, since seed-sellers come and set up booths near the beach to sells seeds for the farmers' annual planting. Even the sea is transformed on a feast: “Fishermen in many places believe that fish in clusters come close to the shore and jump up in joy at the time of their parish feast.”16

In Vettucaud the whole town celebrates Christmas by going to the sea. People head to the beach in the late afternoon of December 24 for swimming and outings in the fishermen’s boats. In the evening there is typically a Mass from 11 p.m. through midnight, after which people dance until 3 or 4 a.m. to music provided by deejays on platforms set up in the streets. By midmorning, people are back at the sea. What perhaps makes this most remarkable is that despite having beautiful sand beaches, this is the only time people use them for other than work purposes. But on Christmas, people of all ages, men and women, will bathe in the sea.

The sense of constant struggle referenced earlier, and the sense of the reality of evil forces in the world also manifests in the saints people are drawn to—conventional saints from the Catholic repertoire who have unusually intense, often altered, followings in the local context. Notable are the “warrior saints” like Santiyagappar (Santiago, Saint James), Saint Sebastian, and St. Michael.17 In the local context, even St. Antony is transformed into a saint with warrior powers over evil. Warrior divinities have been part of Indic religion for millennia, which may help make sense of why these saints, each who is considered not simply venerable, but powerful, are special objects of devotion.

Modern contexts

Coastal Catholic life here is not only shaped by historic forces, but is being influenced by new forces as well. These villages are not backwaters. Kerala is one of the most developed states in India, with high levels of education. Thumba has been home to the Indian Space Research Organisation’s rocket launching station since 1963, an enterprise that supplanted part of the village.18 Construction is now progressing on a huge transshipment container port in Vizhinjam for “megamax” container ships, a feature sure to change life there.

Perhaps more significantly, villagers from this area are very much in contact with the human world beyond. Fishermen are nomads—voyagers—who venture from home to earn a living while the family secures the home. Today, many locals extend those treks abroad in search of work while their families remain home. For some it is permanent, but for many it is temporary. The towns are very close to Thiruvananthapuram International Airport, a gateway to the rest of India and the Gulf States. A significant number of inhabitants emigrate for extended work assignments in places like Dubai, Singapore, Saudi Arabia, and Europe.19 Residents value their own way of life, but are also quite aware how people live in other cultures.

One outcome of that global migration is a building boom. Houses are being expanded and belie far greater affluence than one would expect in a fishing village (space station workers generally live separately, on the station’s grounds). A good deal of the local prosperity is due to remittances from family members who are abroad or savings by those who have returned from abroad. The migrants support and expand homes in India.

A side street shows some smaller houses and a larger one in the background typical of those being built with remittances from family abroad.

Churches, likewise, are undergoing major upgrades, which adds to the sense of religious vibrancy. During the initial research for this account, in 2013, three churches along the coast from Thumba to Vettucaud were being completely rebuilt into extravagant new structures.

Multicultural and multireligious awareness, increasing prosperity, and advancing realms of technology seem to have done little to undercut such intensive religious life, even if they shape it in new ways, though future ways are yet to be seen.

Read more

P. T. Mathew S.J., Between the Sea and the Sky: Lived Religion on the Seashore (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2020).

- 1Kerala, a state with its own distinctive history and language, Malayalam, is 18.6% Christian, a standout in a country where Christians make up only about 2.5% of the population.

- 2P. T. Mathew S.J., Between the Sea and the Sky: Lived Religion on the Seashore (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2020). According to the 2010 fisheries census (Mathew, 19-20), 29% of Kerala fishermen—fishing is an exclusively male occupation, though women do allied work—were Hindu, 28% Muslim, and 43% Christian. In the Thiruvananthapuram region, home of this study, 83.8% of the fishermen are Christian, 14.4% Muslim, and only 1.8% Hindu. Mathew also notes (27-29) that there are clearly defined caste-like subgroups within the Mukkuvar category.

- 3Mathew, Between the Sea and the Sky, 53-55.

- 4Mathew, 54.

- 5Mathew, 97.

- 6Mathew, 73.

- 7Mathew, 73.

- 8Mathew, 72.

- 9Mathew, 57.

- 10Mathew, 74, 79.

- 11Mathew, 80.

- 12Mathew, 80-81.

- 13Mathew, 77-78.

- 14Mathew, 92-93.

- 15Mathew, 77.

- 16Mathew, 57.

- 17Interestingly, Saint George, extremely popular in many parts of Kerala, pictured on a horse slaying a dragon, is not mentioned here. A warrior saint particularly identified with the Eastern tradition, he is popular with both the Orthodox and the Syrian Catholic Christians.

- 18The local bishop and the clergy have played a role in making church property available for setting up the station at the request of the government.

- 19One family interviewed for this project spoke of immediate family members in Singapore, Italy, Ireland, Dubai, and the United States.