Both traditionally and today, family is a primary social institution in Igbo tradition. Catholic belief has altered the concept of the family in limited ways, most notably around the traditional practice of polygyny—men having multiple wives—but has left traditional structures and relationships significantly intact. Modernity and city life also seem to be transforming the family in modest ways, but there are still marked differences between contemporary Igbo and Western or Asian conceptions of the family.1

One key difference is the degree to which the concept of family is broadened from a person’s “nuclear” family, the spouse and children. “While the husband/wife relation is gaining in importance, it is seldom the hub of the system. The father/son or mother’s brother/sister’s son relationships are the traditional emphases in Igbo subcultures with consequences for the radical adjustment of nuclear families in the system which face conflicting loyalties.”2 The “extended” family, then, is central. Parents, siblings, aunts, uncles, cousins and in-laws can make significant social and financial claims on relatives. Even further, though, the extended family and the web of obligation also stretches to include a whole clan or lineage, and even, in very important ways, one’s ancestors.3 Any discussion of family in Igbo culture has to take into account not only how people relate to the living, but how they relate to their ancestors, who continue to impact the well-being and life prospects of the living. Ancestors not only need to be respected, but are regarded as present among the living: the spiritual and material worlds overlap. In common rituals like a kola nut ceremony, ancestors are regularly acknowledged, spoken to, and called upon before other matters can begin. Igbo people live in a covenantal relationship with the ancestors, whose sins can result in punishment being visited upon their children and grandchildren for generations.4 Tradition holds—and has not been wholly undermined—that the ancestors return to rejoin their lineage in the material world through reincarnation.5

Wherever an Igbo person decides to live, “home” will always really be in his or her father’s ancestral village. The extended family there have a claim on him. Urban families will be expected to come back there at least at Christmas, bearing quantities of food and gifts, and wealthy people will build a house there just to be used during those visits. Catholic banns of marriage are read not only where the couple actually live, but in their “home” villages.

Polygyny and concubinage were the dominant forms of adult relationship in traditional society. “The number of wives a man married was not a religious issue before the advent of the missionaries. Plurality of wives was both an economic necessity and a matter of prestige and social status.”6 Catholics are expected, of course, not to have more than one wife, and in the urban context of Enugu I did not encounter any situations where that was the case. But people do speak about that among their grandparents' and even parents’ generation, and polygyny has by no means disappeared.

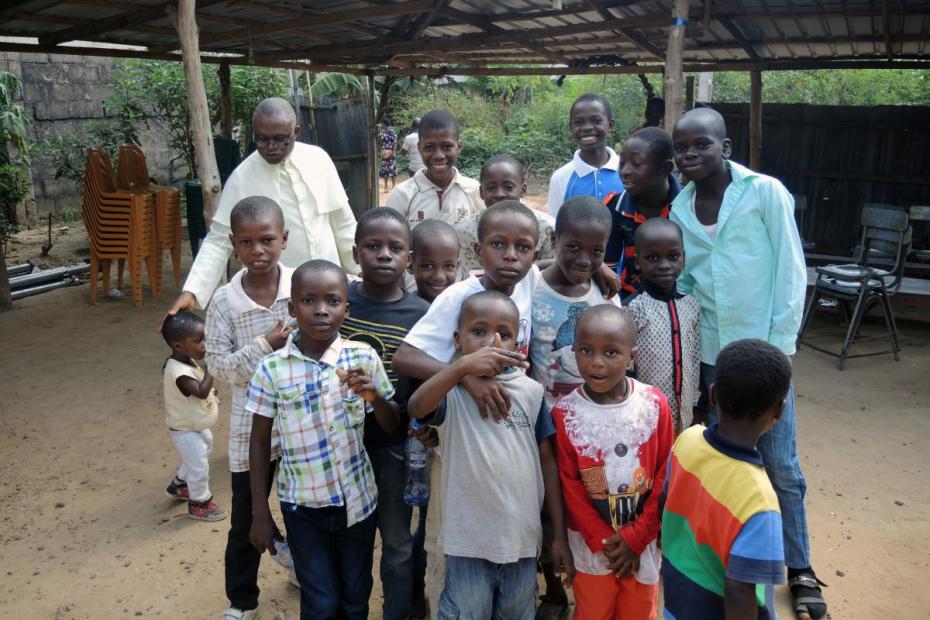

“Until the Catholic Christian religion introduced celibacy as a virtue, an unmarried Igbo male cut a sad figure of hopeless poverty; and the unmarried female was a social disaster.”7 Even today, to not bear children is considered a particular tragedy. As one writer sums it, “The more healthy children [one bears], the better the service by the individual to the community, the greater the sense of self-worth by the bearer of the children.”8 Interviewees said that the size of the family has not decreased and that children are seen as a blessing, but the number of children is said to be lower in the city than in village settings. Adults interviewed in Enugu city typically had 3-5 children. One interviewee was critical about other people having “too big” a family, saying that in such cases, parents could not support or supervise their children adequately, “which is why you see some young people running around wild.” But even he had four children.

The desire to have many children is not only a material need, to insure one’s care in old age, and a social obligation; it is also spiritual. The logic of traditional belief in reincarnation impels carrying on the family line, so that the spirits of the ancestors—and of oneself—can eventually re-enter the visible world.

“The lineage is seen as the building block of peoplehood. To maintain the lineage is a preoccupation reflected in the demands made in prayer: more children and wives and general prosperity to support them are usual refrains. Since women, as wives and daughters, are the general vehicle of lineage continuity, plural marriages are sanctioned everywhere. Furthermore, the concept of paternity, which is central to the legitimacy of children, is given broad interpretation.” 9

Same-sex attraction and relations are a forbidden topic, not even mentioned when people spoke about the sins that beset Nigerians.

Marriage

In a society where clan and village are as important as they are, marriage is traditionally not only a matter of arrangement between individuals, but an arrangement between families.10 Traditionally, families look into the background of each potential spouse, and the male and his father and relatives visit the bride’s family. If she consents, there would be negotiating still to be done, including for a “bride price,” and feasting as well. The potential bride would have spent time with a senior woman in the community, to teach her “how to be a good house-wife, how to please her husband, cooking good food, good relationship with the parents and other relations of her husband.”11 At marriage she would move to her husband's compound and become part of that village for the rest of her life. Her children belong to their father’s lineage.

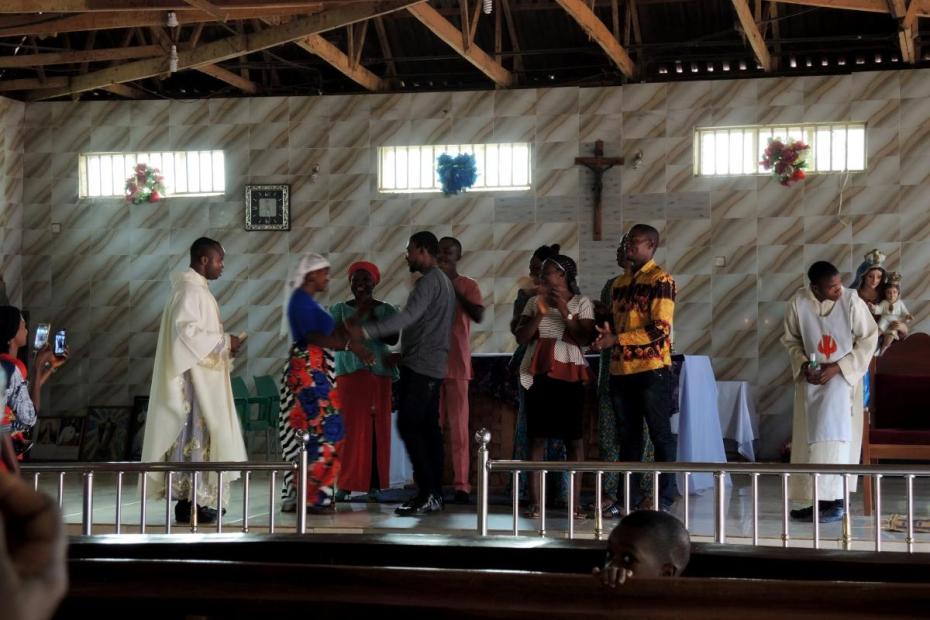

As is true elsewhere, modern situations are affecting this. A bride-price may not be part of the arrangement, or may be only symbolic. At Hearts of Jesus and Mary Parish one morning, two couples were being married together in a small ceremony to regularize their relationships in the eyes of the Church, and no large group of family from the village was present. The women had become part of the parish charismatic group, which facilitated the sacrament.

Women’s roles

In cities like Enugu, women regularly work outside of the household, but are also expected to be deferential to, and supportive of, their husbands. Religious women’s communities have given some increased leadership opportunities to women in the Church, and historians suggest that the Biafran war provided a break that led to increased leadership by women in Catholic lay organizations.

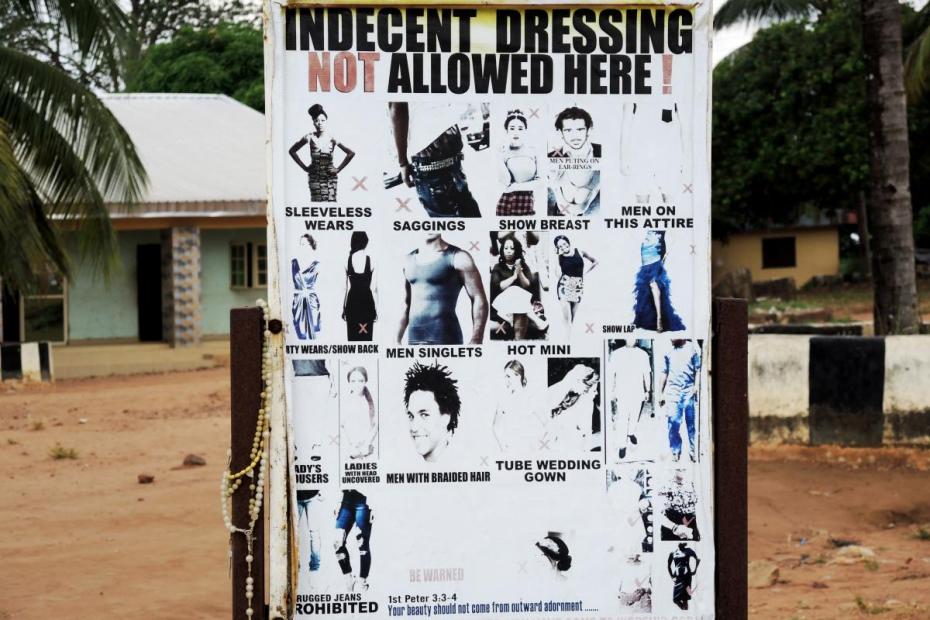

Though so many women work outside the home, and workplaces are integrated, including with women in positions of authority over men, traditional culture, backed by biblical interpretation, provides for clear and distinct gender roles at home and in the Church. In conversation with other men, women defer to men. In group settings, it is mostly women who serve and prepare.

In church, it is particularly noticeable to see women covering their heads, often in the manner of pre-Vatican II Catholicism. One man denied that it was because of pre-Vatican II Roman tradition. “In traditional culture, women are expected to cover their heads as respect for their husbands.” Several women and men said that it is important because it is in the Bible (1 Corinthians 11:2-16). “If you don’t cover your head, they will see you as a sinner,” said one. A visitor from East Africa, where women covering their heads is not part of the culture, reported that she tried to go into church in Enugu without covering her head, and the women stopped her and insisted that she do so. It made her mad, but the women would not relent. Traditional culture forbade women from wearing the clothing of men. Today, women wearing pants to church would be put out. Whether for men or women, though, Igbo culture expects modesty in terms of dress, especially in places considered holy.

The family home as a place for prayer and moral upbringing

The parish families I interviewed talked about how many times a day they prayed as a family—most prayed the Rosary at least once. Those with adult children said that their young adult children continued the practice. Homes typically displayed a Bible, a Sacred Heart image, a crucifix, or an image of Jesus with children, and at least one image of Mary.

When people talked about the values that they wanted to inculcate in their children, or when children talked about what they learned about what it meant to be a good person, they overwhelmingly talked about obedience, humility, and listening to their fathers and mothers. As one summarized it,“the Bible teaches these values.”

- 1This entry is based on interviews, home visits, and informal conversations with more than 30 Igbo Catholics over the course of eleven days in greater Enugu in December 2019. Particular thanks to parish station catechist Odoh Basil A.; Fr. Paulinus Ike Ogara, and pastor Fr. Theophilus Enebechi and the people of Hearts of Jesus and Mary Parish and its mission stations for their warm hospitality.

- 2Victor Chikezie Uchendu, “Ezi Na Ulo: The Extended Family in Igbo Civilization,” Dialectical Anthropology 31, no. 1–3 (2007): 185.

- 3Austin Echema, Igbo Funeral Rites Today: Anthropological and Theological Perspectives (Munster: LIT Verlag/Piscataway: Transaction, 2010), 22.

- 4Uchendu, “Ezi Na Ulo,” 178-9.

- 5C.N. Ubah, “The Supreme Being, Divinities and Ancestors in Igbo Traditional Religion: Evidence from Otanchara and Otanzu,” Africa 52, no.2 (1982): 102.

- 6C. N. Ubah, “Religious Change among the Igbo during the Colonial Period,” Journal of Religion in Africa 18 (1988): 77.

- 7Uchendu, “Ezi Na Ulo,” 175.

- 8George Nnaemeka Oranekwu, The Significant Role of Initiation in the Traditional Igbo Culture and Religion: An Inculturation Basis for Pastoral Catechesis of Christian Initiation (Frankfurt: IKO Verlag, 2004), 121.

- 9Uchendu, “Ezi Na Ulo,” 215.

- 10Oranekwu, The Significant Role of Initiation, 111.

- 11Oranekwu, The Significant Role of Initiation, 112.