Orthodoxy in Ethiopia is much more a faith built on liturgy and spoken prayer than on systematic theological reflection about beliefs.1 Catholics regularly differentiate themselves from Orthodox by stressing the degree to which they learn catechism. Nonetheless, compared to many other countries, Catholicism here also places special stress on the way that the liturgy communicates the faith.

Catholic liturgy is celebrated in Ethiopia both in the Ge’ez (or Ethiopian) rite and the Latin rite. Whereas in some countries there are parallel Latin and Uniate Catholic hierarchies and distinctive churches for each liturgical rite, Ethiopia is home to a single Catholic Church and clergy that celebrate both liturgies. Ge'ez is an ancient court language from the period when Ethiopia first adopted Christianity. It carried down as the liturgical language even as it fell out of use otherwise, and is regarded with pride as a symbol of the ancientness and rootedness of the faith in Ethiopia. Much like Latin in the west, many lay people do not understand the language, so a number of parts, like the readings, are in local languages like Amharic.

The Latin rite liturgy is celebrated in the vernacular, in a shorter 45-minute service, and may incorporate more contemporary music and movement.

Orthodoxy as a model for Catholic liturgy

The Ethiopian Orthodox liturgy lasts for three hours. The curtain of the sanctuary is open for some of the time in the middle of the liturgy, but older churches in particular are not built with the expectation that the whole worshipping community can be housed in the building. Orthodox churches generally have no seating. People stand during the liturgy, women in one section, men in another. Many will stand at the doors of the church, out of a sense of deference or unworthiness. Those who think of themselves as unclean, especially for reasons of sexual impurity, might position themselves outside of the building, where they can hear but not see the liturgy.

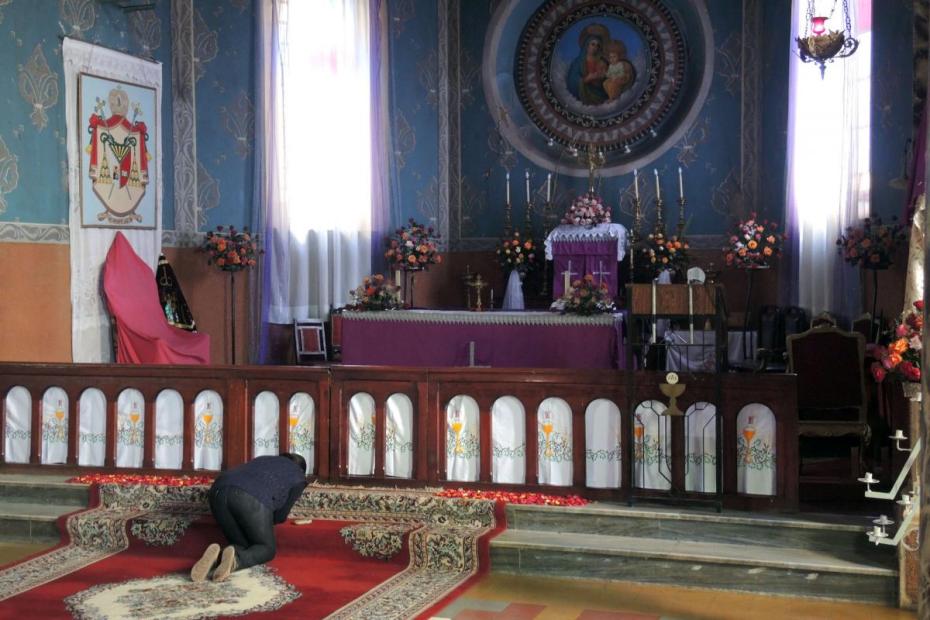

The Ethiopian (or Ge'ez) Catholic rite is an adaptation of that Orthodox Ge'ez rite. In important ways, the liturgy reflects and transmits some key Ethiopian values, such as patience, deference, humility and modesty. These attributes are readily visible in the postures of worshippers.

Like Orthodox, Ethiopian Catholic liturgy lasts very long – typically two, but sometimes three hours, and its action focuses in particular on the clergy, deacons and assistants on the altar. (In the video on this page, there is a full complement of priests, deacons, and lector, plus the archbishop; in parish settings there might be only two celebrants.) The primary attitude is reverence and worship, not community-building in a post-Vatican II Euro-American sense. Interestingly, though Ethiopian culture tends to look down on ostentation, the clergy are dressed splendidly during liturgy. The style of vestments are more Orthodox than Roman.

The Catholic liturgical year, like the Orthodox, is organized around the traditional Ethiopian church calendar that derives from the ancient Coptic calendar and the Julian (pre-Gregorian) Roman calendar.

Whereas the Orthodox tend to receive communion primarily as children or in old age (and apparently refrain during years of sexual activity, including for married people), Ethiopian Catholics are happy to explain that the Eucharist is more accessible for them.

Women at Catholic liturgies usually sit separately from men, a pattern that is more strictly held in Orthodox churches, which have different entrances for men and women. At Catholic churches, families might sit together, or women might mix, but as one woman reported, “I have never seen any man who joined the women’s side. Never. I go to many Catholic churches… If the places are full, it is the women who join the men’s side.”

While the Ethiopian Catholic rite entails a good deal of clerical movement around the altar, plus standing, kneeling, singing, and simple gestures by the faithful, it is a liturgy that is fairly restrained in the scope of its movement. Adherence to form is important. Catholics in Addis Ababa, the Ethiopian capital, express discomfort with the dancing and freer movement that they see in more southern African liturgies, including the liturgies of some southern Ethiopian peoples. From a northern Ethiopian point of view, these are described as too "sexual" and unrestrained. One notable exception to that restrained quality is the tendency of women to ululate at moments of approval and welcome in the liturgy. Several Ethiopians suggested that this is something that middle age and older women tend to do, that younger women are less comfortable with.

Though not observed directly for this project, many of the southern peoples of Ethiopia, from ethnic groups conquered by Ethiopia in the 19th century, are said to have a much different ideal for worship, involving more movement and celebration than would be found in the dominant national forms. Most of these peoples are converts from animist traditions in the last century.

In traditional Ethiopian Orthodox churches, the altar and sanctuary are enclosed, but are partially made visible by the opening of a screen or curtain at some points in the liturgy. Latin rite churches worldwide are normally designed with the sanctuary open to the people, so as to make the worshippers' sight lines to the altar a priority. Ethiopian Catholic churches are designed both ways. The cathedral in Emdibir, in the Gurage region of the countryside outside Addis Ababa, was recently redecorated and screens the sanctuary with iconographic images in a more traditional Orthodox fashion. On the other hand, Kidane Mehret (The Covenant of Mercy),2 a newer Catholic church in Addis Ababa, is built in the completely open Latin style, like the other Catholic churches in Addis. These churches are sites for the celebration of both the Latin rite and the Ge'ez rite liturgy. Yet each design gives very a different perspective on the mystery or accessibility of the Eucharist.

Both reverence and disconnect with Ge'ez rehtite

Catholics in Ethiopia speak of the role of liturgy in two ways. A large number - seemingly most Catholics - have a deep love for the Ge’ez rite, and speak of its beauty in an almost rhapsodic way. At the same time, some speak of a fear that too many young people in the city cannot connect to the liturgy, or understand it, and hence find Protestantism more attractive. Some see the Latin rite as a “middle way” through this. In small ways, the Church seems to be adapting in places. At the cathedral in Addis, a small youth choir with synthesizer music is brought in to provide one or two more contemporary (Catholics often label them “Protestant,” in contrast to the Ge’ez chant) songs. Another more rural diocese prevents such adaptation in church but allows such Christian music in other settings.

The history of the Latin Church in Ethiopia certainly provides impetus for preserving the Ge’ez liturgy. Jesuit missionaries in the 16th and 17th centuries tried to force Latinization on the church, a strategy that failed badly. The next effort by the Roman Church, beginning in the mid-19th century, had to stress inculturation much more, and has done so to an increasing degree over time. For many Ethiopians, sense of pride in their liturgy as a cultural legacy runs deep. Its ritual and musical forms are points of pride that define the Ethiopian Orthodox and Catholic identity. Even this is complicated by the fact that many Ethiopians from South and Oromia regions consider Geez liturgy a legacy of the Amhara, whom they often derogatively call neftegna ("he who controls over through gun"), given that feudal landlords in the South for more than a century were mainly Amhara.

- 1Clerical training in Orthodoxy has long centered on reading, memorization of prayers, and liturgical practice. For a good description of this see "Priest," "Priest's [sic] School" and "Clerical Education" in Amharic Cultural Reader, ed. Wolf Leslau and Thomas L. Lane (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2002), 95-107.

- 2The name is the same as that of another Orthodox church in Addis