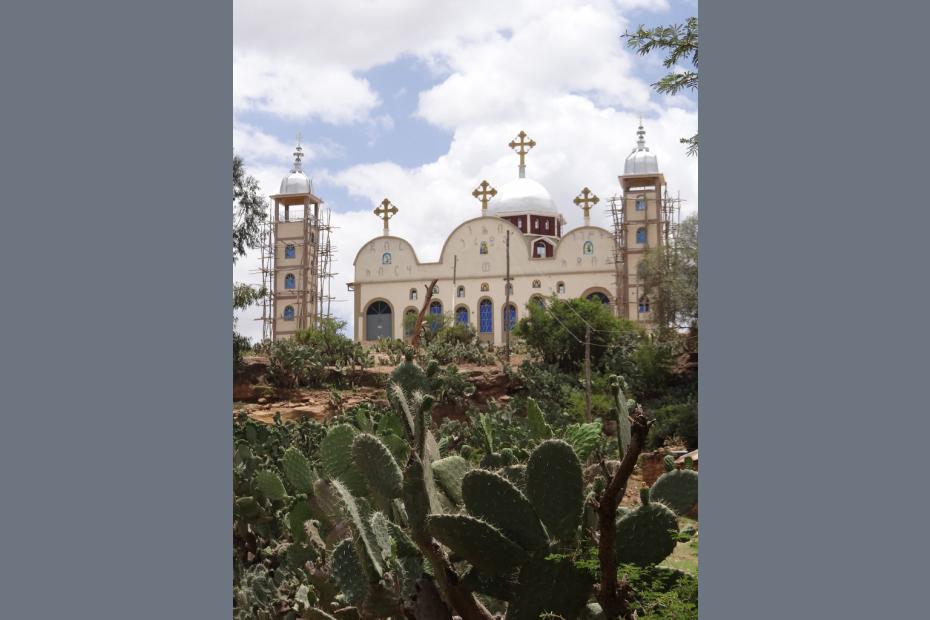

Despite its location in the midst of a band of Muslim countries in the Horn of Africa, Ethiopia stands out as a country whose identity has been defined by a rich, ancient and quite distinctive Ethiopian Orthodox Christian heritage. Ethiopia is home to a sizeable Muslim population,1 but the Ethiopian Orthodox heritage plays the largest role in shaping the official national self-conception. The scholar Peter Brown describes the Ethiopian city of Axum as one of the "cultural centers of the worldwide Christian church" in the seventh century.2

Catholicism is a tiny minority faith there, a faith whose practice and standing are very much shaped by the practice and standing of Ethiopian Orthodoxy in the national story. In the dominant national historical narrative, Ethiopia is a Christian country whose roots are intertwined with the ancient Israelites and the Hebrew bible.

Ethiopia stands out on its own and in the broader African imagination as a state that resisted European conquest and forged an independent identity over the centuries. Occupation by Mussolini's Italian troops in the 1930s brought elements of Italian culture to Ethiopia, but also complicates the place of Roman Catholicism in Ethiopian culture.

The modern state, the legacy of an empire whose boundaries were largely settled in the 19th century, is comprised of 80 ethnicities speaking as many languages and 200 dialects. Three ethnic groups make up the bulk of the population: Oromo, who comprise about 35% of the population; Amhara, who comprise about 30%; and Tigrayans, who comprise about 10%. These proportions are often debated, but ethnic competition is a significant factor in politics and in ordinary life and relations. This pluralism radically complicates any effort to discuss faith and culture in Ethiopia, though it is accurate to describe the dominant culture of Ethiopia as Orthodox Christian and Amharic.

While Christian Amhara and Tigrayan peoples point to the ancient Ethiopian Orthodox tradition as their core cultural patrimony, Oromo and Southern peoples conquered by the northern kingdom in the 19th century have other — usually animist — traditions as their cultural and religious patrimony, and often have to be more aware of how to reconcile their traditional patrimony to Christian belief. Oromo culture and language were vigorously suppressed until the overthrow of Haile Selassie in 1974. Amharic culture is said to be more hierarchical and patriarchal, while Oromo culture and other southern cultures are said to be more democratic, egalitarian and deliberative.

Currently, information for Ethiopia on the Catholics & Cultures site relates primarily to the dominant Christian and Amharic tradition, and to the capital region of Addis Ababa, though the interviewees in Addis Ababa come from a wide variety of ethnic backgrounds. These stories also examine some aspects of Gurage culture in two rural areas in the region surrounding the capital.

Biblical legacies

Though the last monarch, Haile Selassie, was overthrown in 1974, Ethiopian national identity has long been defined by monarchs who claimed a line of succession to Israel’s King Solomon and Ethiopia’s Queen of Sheba. One of those monarchs, King Ēzānā, adopted Christianity in 333 AD, after which the Ethiopian Orthodox Church became a major source of national cultural identity. Ethiopian Orthodoxy, like Ethiopian national identity, is linked to many biblical roots: According to the Bible, Moses’ wife was Ethiopian3 and the kingdom is mentioned many times in the Old Testament, including in the Psalms of David.4 The 14th-century, national epic Kebra Nagast, The Glory of the Kings, even claims that the Ethiopian nation was founded by Etiopik, a great grandson of Noah, and that Menelik I, son of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, brought Jewish nobles and the Ark of the Covenant back from Israel. Amharic Ethiopians have thus understood themselves genealogically as heirs to the King Solomon and these nobles. They believe that the church of St. Mary in Axum is home to the authentic biblical Ark of the Covenant.

That legacy provides contemporary Ethiopian Orthodoxy with a number of practices and beliefs not shared by other Christians, especially contemporary Orthodox and Catholic dietary rules that have parallels to kosher rules. Every Orthodox Church contains a copy of the tabot, the Ark of the Covenant, which is venerated and kept behind a veil. Male circumcision on the eighth day after birth is also historically associated with Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity.5

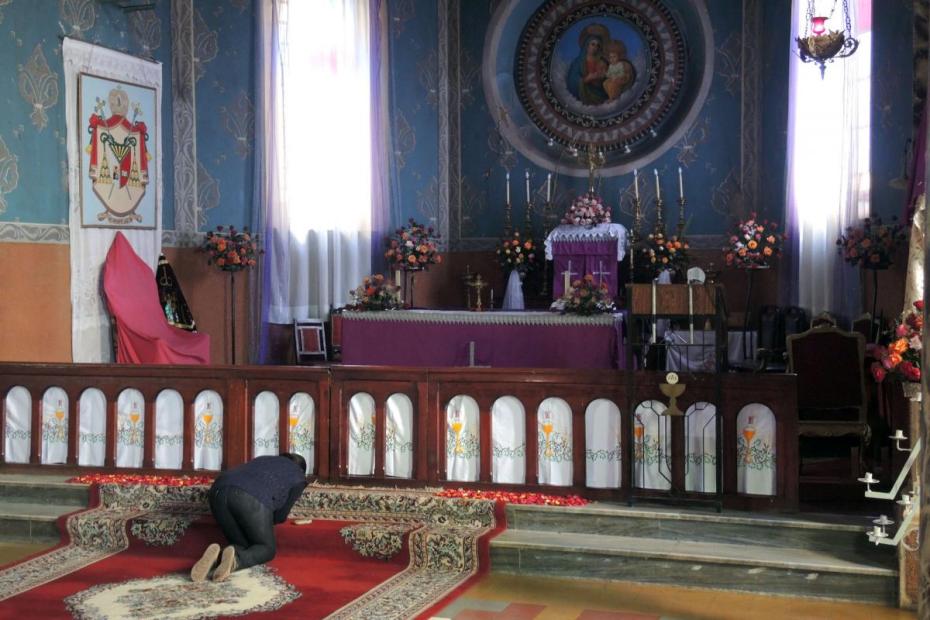

Orthodox liturgy is celebrated in Ge’ez, the court language at time of King Ēzānā’s conversion in the fourth century. The Ethiopian Catholic rite follows many of these same cues.

Colonialist, Latinizing efforts by the Jesuits in the 16th century and an Italian political occupation under the Mussolini regime complicate the standing of Catholicism in the country. In Addis Ababa, Catholics say that they are accorded a welcome place in society, and are especially respected for the schools and social institutions that Catholic religious orders sponsor. Some said that the 16th-century Jesuit legacy still leads to hostility toward Catholics. In the countryside, especially where Catholics are few, they report being misunderstood in a range of ways, and even lumped in with groups like Seventh Day Adventists.

Catholics interviewed in Ethiopia described their Church as less restrictive and more “modern” than the Orthodox Church, and seem to appreciate the degree to which their Church bridges the modern and the traditional. At the same time, when asked whether they saw the primary role of the faith as liberal or as conservative of good social norms, all of the interviewees, even among highly educated urbanites, saw the role of the Church in the latter terms. There are liberationist perspectives in the culture but these are hopes placed in the government, not the Church.

Catholics do not significantly define their faith against Orthodoxy, so much as in relation to it, as a norm at times and as a point of departure at other times. They express pride in the legacy of hospitals, schools, and education that make it stand out. They will often describe themselves as more “liberal” in terms of practice around fasting or the fact that they do not remove shoes when going into church. They speak of their faith as one that involves a greater level of catechesis in terms of the meaning of beliefs, compared to Orthodoxy, and often volunteer that the primary difference is that they accept God as fully human and fully divine, unlike the Ethiopian Orthodox monophysite theology. On the other hand, they are careful to distinguish themselves from Protestants, especially Pentecostals or Jehovah’s Witnesses, whose faith is seen as too foreign, but which has made significant inroads in Ethiopia in recent decades.

Whereas in some parts of the world Eastern rite bishops and dioceses function independently of the Latin rite, in Ethiopia the Latin rite and Ethiopian rite are united in that all Catholics in a region come under the same jurisdiction, and can choose to worship in the Ge'ez or Latin rite.

Urban centers, particularly Addis Ababa, are well connected to the larger world, but the vast majority of the Ethiopian population is rural and depends on subsistence farming and nomadic herding. Television and the web are finding their way via satellite dish to the countryside, and there is greater awareness of foreign values and of the material prosperity that can be seen on these media.

One interviewee who had spent time in Germany noted how much more likely he was to see young people in Catholic churches in Ethiopia. But he also noted that in terms of systematic, theological understanding of the faith, Germans came out far ahead. Ethiopia, as he described it, is a place where Catholicism is a religion of practice more than it is a place where people emphasize reflection on the meaning of practice. Ethiopians were tied to faith deeply, but the kinds of theological questions that preoccupied Germans were not to be noticed in Ethiopia. The same interviewee expressed frustration that Germans found it funny that he believed holy water could have the power of healing. People in Ethiopia, he said, see healings and miracles, and see devils cast out, and believe in them.

Read more:

Amharic Cultural Reader, Wolf Leslau and Thomas L. Lane, eds. Wiesbaden, Harrassowitz Verlag, 2002. (The volume includes accounts of various cultural aspects of Amharic Ethiopian life collected in the 1950s and 60s, though with some continued relevance today).

- 1The proportional representation of Muslims and members of other faiths in the country, as reported in the last census, is a matter of debate in many parts of the country. For a history and appraisal of the relationship between Christianity and Islam, see Hussein Ahmed, "Coexistence and/or Confrontation?: Towards a Reappraisal of Christian-Muslim Encounter in Contemporary Ethiopia," Journal of Religion in Africa, 36.1 (2006): 4-22.

- 2 Peter Brown, "At the Center of a Roiling World," New York Review of Books, May 11, 2017, 50.

- 3Numbers 12:1. In the Hebrew bible, Ethiopians are referred to as Cushites.

- 4Psalm 68:32.

- 5See Steven Kaplan, "Male Circumcision" in Encyclopaedia Aethiopica, vol 1., ed. Siegbert Uhlig (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2003), 748-9.