One of the enduring—and literally compelling—aspects of Igbo traditional culture is the practice of naming. In traditional culture, names have real meaning and power. “Igbo names are not mere tags to distinguish one thing or person from another; but are expressions of the nature of that which they stand for.”1 While Igbo names can simply refer to the circumstances of birth, as in the case of a child born to parents who had been unable to conceive, or simply in reference to the day of birth, more often they send a theological message or a compelling reminder of a certain expected virtue to be instilled in the child. In traditional culture, “an Igbo child at birth is dedicated to a god called a chi, who is responsible for the guidance and protection of that child.”2 Today, parents still choose Igbo names to carry on that tradition in Christianized fashion.

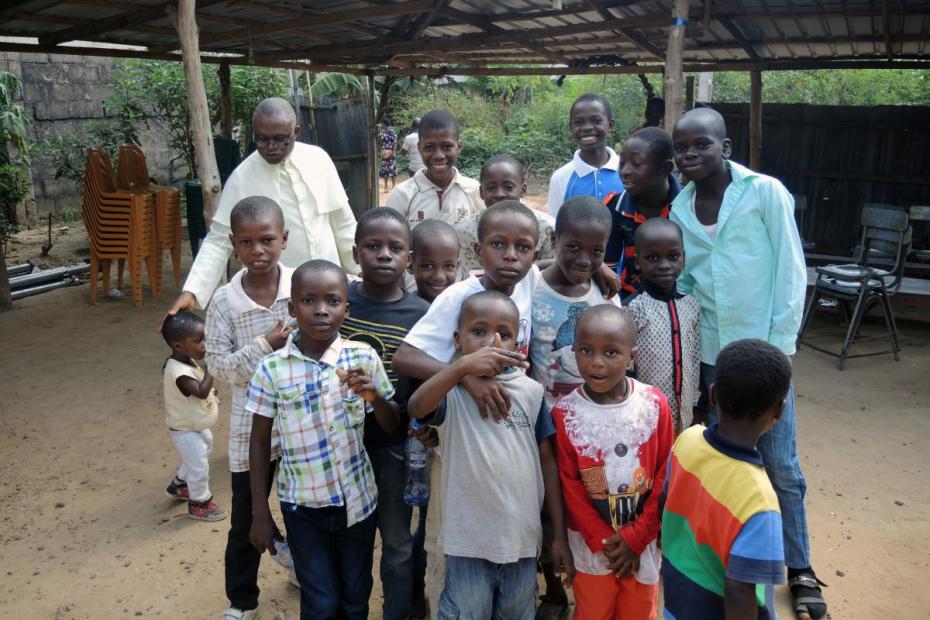

The power of names was immediately apparent in a gathering of small children one evening in front of Hearts of Jesus and Mary Parish, where each child was eager to share their names, and their English translations: “Akachukwu, ‘Hand of God’”; “Osinachi, ‘It comes from God’”; “Daberechi, ‘Depend on God’”; “Chinecherem, ‘God thinks for me’”; “Ezinne, ‘Good Mother.’” One scholar describes such names as “theophanic,” expressions of God’s presence with the named person, “fruits of Igbo people’s experience of the divine.”3 Something about the children’s ease with sharing and translating those names to English communicated such an awareness and experience. An extraordinary number of the names one encounters have Christian meaning as adaptations from traditional names: Chimamanda means “God Will Not Fail Me.” Ngozi means “blessing.” NgoziChukwu means “blessing from God.”

Most Igbo Catholics have a combination of Western—typically saints’—names and traditional Igbo names. Initially, the Church tried to insist that only saints’ names were used, and then shifted to saying that children must, if they have a traditional name, also have a Catholic saint’s name for baptism. That transition became easier as people transformed their perception of the beings behind traditional Igbo names to refer to the Christian God. Thus Chukwu (from Chi-Ukwu, the Supreme Chi, or the supreme Being), the traditional name for the Creator, has an enduring place, as does “Chi.” Now Chukwu and Chi are used in Christian naming to refer to God in a Christian sense, and are referenced in the children’s names above. Two long lists of girls’ and boys’ names, so many of which contain “Chukwu” or “Chi,” make clear how religiously imbued the names people choose are.

The Catholic names one hears—from the children, Veronica, Perpetua, Ezekiel, Elijah, Emmanuel; from adults, Stella, Rita, Jacinta, Thaddeus, Theophilis, Francis, Fidelis, Malachy, John Bosco—draw from a deep and old Catholic canon, deeper than is common in the European world today. There is no longer usually a requirement to pick a Western saint’s name, but the habit endures.

Iguaha: Naming ceremony

Igbo names are not merely chosen, but traditionally were conferred at home in a ritual defined by tradition and typically distinct from the baptismal ritual, which is conducted at church. These rituals continue in more or less original form among the small minority who still identify exclusively with traditional religion, and have been adapted by Catholics. Not all Catholics practice the ritual, but in adapted form it is still meaningful to many.

The traditional form is roughly as follows, with variation from village to village: After a baby is born, a diviner is consulted to identify “which of the ancestors reincarnated through the new baby.”4 The family would offer a sacrifice, bury the umbilical cord, and shave the baby’s head.

The child’s naming ceremony takes place seven, eight, or twelve days later. The ceremony begins with the blessing and breaking of a kola nut by an elder family member in the paternal lineage, which calls forth the ancestors and family deities, seeking their protections and blessings on the child and living family.5 Some pieces of kola nut are tossed to the ancestors, while the rest is shared among the family. Other food and palm wine is shared, and the baby is brought out by the elder, held up to the heavens, and admonished with words like these: “When your mother speaks to you, listen to her! When your father speaks to you, listen to him! Open your eyes in the day! And sleep in the night!”6 The ritual welcomes the child, introduces him or her to the ancestors and shows the ancestors and the deities that the child has been properly welcomed and will be properly taught. In one account, it tells the child, “Remember that you are one of us.”7

“Traditionally a sacrifice of a cock for a boy or a hen for a girl was also offered to the ancestors at the family shrine and they were invoked to protect the child and to give him a long life. The elder kinsmen then pronounced their wishes for the child.” 8

The culmination of the ceremony is the act of naming by the father. As John Mbiti asserts, “This ritual is the seal of the child’s separation from the living-dead, and its integration into the company of human beings.”9

The power of naming, not just for the individual

The belief in the power of naming may carry over in one interesting way. Though Catholic culture is only modestly visible in Enugu, in small but not highly aestheticized ways, it is noticeable in the way that religious names are sometimes carried over to businesses and secular enterprises: “More Grace Clothing Store,” “St. Jude Tailor,” “Christ the King Photos & Video,” “Divine Dove Driving School,” “God's Time Bridals & Fashion Home.” To be sure, many more businesses, especially larger ones, use commercial, modern names, but the number of micro-sized businesses with Christian-sounding names still stands out. Like the tradition of naming a child in a way that confers added meaning and purpose in her life, so too does it seem to add meaning and purpose to some businesses.

- 1C.O. Obiego, African Image of the Ultimate Reality: Analysis of Igbo Ideas of Life and Death in Relation to Chukwu (Bern/Berlin: Peter Lang, 1984), 32.

- 2Jacinta Chiamaka Nwaka, “The Early Missionary Groups and the Contest for Igboland: A Reappraisal of Their Evangelization Strategies,” Missiology 40, no. 4 (2012): 416.

- 3Chibueze Udeani, Inculturation As Dialogue: Igbo Culture and the Message of Christ (Brill, 2007), 43.

- 4George Nnaemeka Oranekwu, The Significant Role of Initiation in the Traditional Igbo Culture and Religion: An Inculturation Basis for Pastoral Catechesis of Christian Initiation (Frankfurt: IKO Verlag, 2004), 100.

- 5The description that follows paraphrases, in abbreviated form, that of Oranekwu, The Significant Role of Initiation, 100-103.

- 6Oranekwu, The Significant Role of Initiation, 101.

- 7Mary Steimel Duru, “Continuity in the Midst of Change: Underlying Themes in Igbo Culture,” Anthropological Quarterly 56, no. 1 (1983): 6.

- 8Duru, “Continuity in the Midst of Change,” 6.

- 9John Mbiti, African Religions and Philosophy (London: Heineman, 1975), 120, as cited in Oranekwu, The Significant Role of Initiation, 102.