China’s political and economic transformation is undoubtedly one of the most remarkable events of the last several decades, as a country of 1.4 billion people rose from poverty, self-isolation and political chaos to become much more prosperous, globalized, and influential on the world stage. These years have also seen a re-blossoming of China’s religious life, including Catholic life. Western media accounts of Catholic life in China often focus primarily on Sino-Vatican relations and the sometimes-contested status of episcopal appointments in China, but among ordinary Catholics, religious practice is flourishing and evolving in a variety of fascinating ways, as the Chinese Catholics find their place in the larger Catholic world and discern how to respond to so many changes in Chinese society.

The burgeoning number of Christians is a surprising turn of events, considering that the country is rapidly modernizing, and that it totally banned religious practice as recently as 1976.1 Estimates of the number of Catholics in China today range from about 6 million to 12 million, up from about 3 million in 1949.2 Catholics constitute about one-half of one percent of the population, about the same proportion as before the Revolution.3 The most substantial growth, however, has been among Protestant churches, which used to be collectively much smaller than the Catholic Church in China, but today are far larger.4 The fact that Catholicism’s comeback has been less robust than Protestantism’s points to challenges specific to Catholicism in this context. Compared to the Protestant Churches (which have their own organization similar to the Chinese Patriotic Catholic Association), Catholicism’s position in China has been complicated by the fact that the Holy See is a sovereign state, a “foreign power,” while all institutions in China, including recognized religions, are expected to be fully nationally controlled.

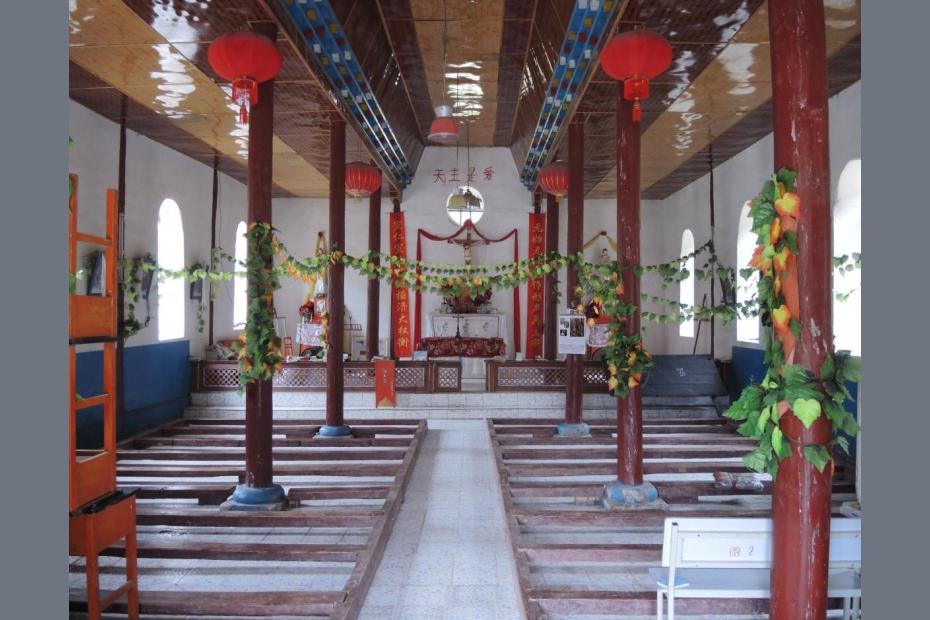

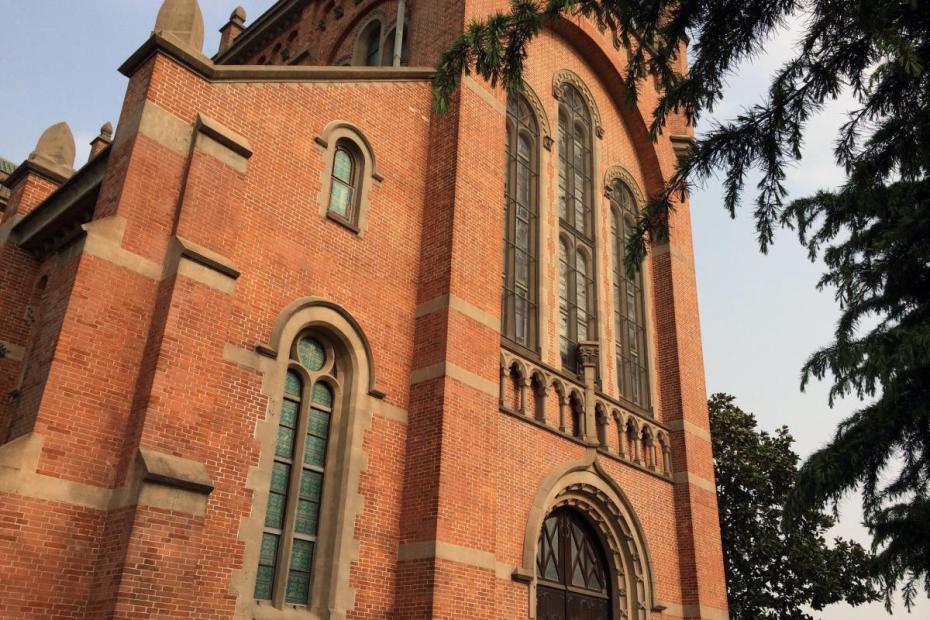

China is governed by a Party that is officially Communist and atheist, and that exerts various forms of oversight and control over everyday life that would not be accepted in many countries, but largely is in China, as a form of social compact for the successes that have been achieved, and of course in part by sheer power. Yet it is also fair to say that China is transformed, open, free and capitalist to a degree that no one imagined 40 years ago. The lived, daily experience of Chinese Catholics is therefore a story of both opportunities and limitations, manifest in inconsistencies that can often seem arbitrary. In recent years the government has expressed repeated demands for a policy of "sinicization" or "religion with Chinese characteristics," which is not a way of saying that images of the Virgin Mary should look more Chinese, but rather of saying that the Party must have an essential role in overseeing and shaping any religion in China. In terms of concrete actions, one might hear of the forced removal of crosses from church spires in one province at one point, even as the government continues to aid in the rehabilitation and construction of major Catholic churches in other parts of the country, or to move forward episcopal ordinations jointly approved with the Holy See.5

Freedom of religious belief is guaranteed in China’s constitution, but not freedom of religious association.6 The Party “insists that religion should support, rather than disrupt social order and that churches cannot be subject to any foreign authority. Beijing’s leaders continue to uphold the historical perspective and the view that the government must oversee religion”7 lest religion become a subversive force in society. Neither Catholicism nor religious practice is singled out for special treatment or control by the government, but the degree of control affects the growth and character of Chinese Catholicism.

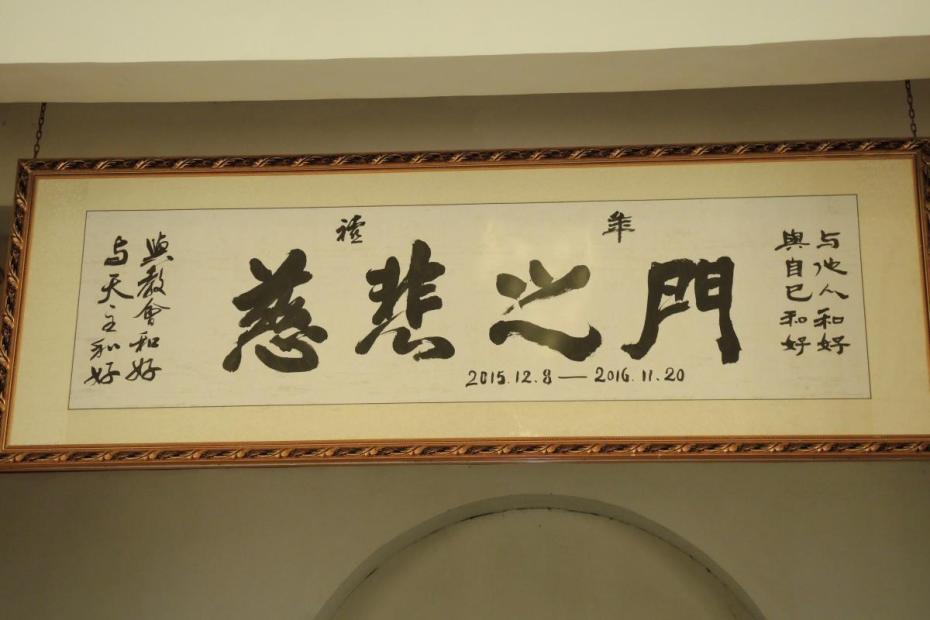

For centuries, culturally and politically, harmony and stability have been core themes of Chinese life. That emphasis helps shape Chinese Catholic life, as it has for generations. Banners adorning churches, homes and public places extol harmony and Chinese virtues, and Catholics often “justify” the value of the faith in China in terms of its contribution to stability. The justifications do not suggest that Catholics’ morals should be radically different from other Chinese, but that Catholicism helped Chinese live up even better to the cultural ideals that they all professed in common.8

Historical background

Christian presence in China has expanded and contracted in waves for much of Christian history. It originally dates to the seventh century, when Syriac Christians from the Church of the East arrived and gained a small foothold. Franciscans traveling along trade routes to China in the early 13th century also had some temporary success. In the 16th century, Jesuit missionaries arrived and gained important positions at the imperial court, making it possible for them to preach in many regions. Their achievements in the arts and sciences had a lasting impact and are celebrated in China today, but their missionary impact was cut short when, in 1704, the papacy condemned the Jesuits’ accommodation to a number of Chinese religio-cultural practices, particularly the veneration of ancestors. Foreign missionaries were subsequently expelled, and Christians were persecuted as a threat to social order.9 Catholicism survived, but did not really begin to flourish again until the mid-19th century, when missionaries gained a stronger foothold as European powers pushed into China, and the weakened Chinese imperial system was forced to accommodate them.

The 19th and early 20th centuries were a time of significant growth in the Catholic Church in China, even though the first half of this period was also marked by acts of resistance and bloodshed by traditional forces that turned into international incidents.10 Catholic missionaries’ association with the European and American powers often helped the Church to grow, and by the eve of the Communist Revolution, the Church in China had 3 million members and a significant and growing number of Chinese leaders. Catholic communities often memorialize and celebrate the work of their missionary founders, but in the larger Chinese context the missionaries’ historical connection to the “era of national humiliation” has repeatedly rendered Catholics vulnerable to backlash.11

After the Communist Revolution of 1949, missionaries were expelled from the country, and many Chinese Catholics suffered tremendously in jail for their faith, foreign ties, and opposition to Communism. In 1957 the government and some Chinese Catholic leaders founded an independent national association, the Chinese Patriotic Catholic Association (CPCA), to take over the leadership of Catholic churches in China. The CPCA was designed as a mechanism to monitor and link Church and state in China and to sever ties to the Vatican, which was considered a foreign power.12 The history of Catholicism in China certainly gave credibility to nationalist agendas to eliminate “foreign domination over the churches,” though it was equally true that the state aimed to make the churches, insofar as they were allowed to survive, into tools of the Party. Catholic clergy and believers were expected to forswear any ties to Rome. Many Catholics joined CPCA churches, and others continued to worship underground, independent of the scope of the Patriotic Association. Parallel and generally independent Catholic hierarchies overlapped in China, though the Patriotic Association was never declared by Rome to be in schism.

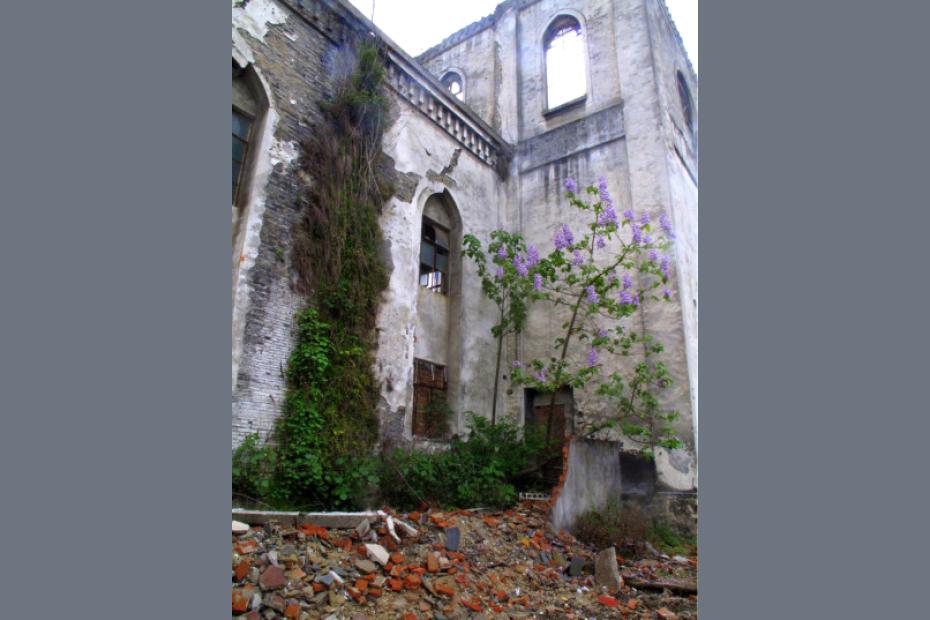

During the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), a period of intense political and social upheaval that completely upended every aspect of Chinese life, religious practice was totally suppressed and persecuted. Public practice disappeared entirely, and even private devotion was subject to violent persecution. Churches were destroyed or converted to factories or warehouses.

After 1978, as new political leaders sought to move China out from the shadow of the Cultural Revolution, churches in a number of major cities began to reopen, fostered by the initiative of local Catholics, with support and even partial funding from local and state Communist party officials, as well as from donors abroad. The history of persecution and betrayal left many fractures in the communities, but also cemented the identity and resolve of many Catholics. Researchers who study that era suggests that while the hierarchy of the “above-ground” and “underground” churches often squabbled, lay Catholics were especially important in taking the lead on evangelization.13

Since then, the Vatican and the Chinese government have variously seemed to take steps toward reestablishing relations, only to fall backward. On the ground, though, matters of liturgy, practice and theology have moved toward normalization. Catholics who had entirely missed the reform era of Vatican II during the Cultural Revolution came to learn about the many ways that Catholic practice and belief had changed as a result of the Council. Until 1994, when the Shanghai diocese translated the liturgy into Chinese and published and circulated sacramentaries all over the country, the liturgy was still in Latin under the old form. CPCA churches and “underground” churches have worked to conform Catholic life to new global norms, though not all have been prepared to leave behind the pre-Vatican II practices that sustained their religious imaginations. As China modernized and sought to leave behind the excesses of the Cultural Revolution and to connect with the West, Christianity even took on some cultural cachet.

'Above-ground' and 'underground,' 'registered' and 'unregistered'

Any attempt to write about Catholic life in China is muddled by the continued existence of two groups of Catholic believers in China, those who belong to the CPCA and those who practice independently of it. The distinctions implied by the terms “above-ground” and “underground” are sometimes meaningful, but are also, in the present-day situation, often more confounding than helpful. Surveillance is ubiquitous in China. It would be almost impossible to hide a church community from government eyes in the manner that "underground" implies. The political implications of the affiliations are often not what one would expect. Terms like “official” and “unofficial,” or “registered” and “unregistered,” are often offered as alternatives.14

Betty Ann Maheu writes, “Churches are either registered or unregistered. Government regulations require places of worship to be registered. Open, official or government-approved churches are all registered. Underground churches are unregistered, and sites of worship that refuse to register are illegal and subject to closure and repression. Authorities in different places, however, deal very differently with both the registered and unregistered groups.

“The underground church is not literally in hiding. In certain areas that I have visited, the church is large and beautiful, built in view of everyone in the middle of the city. On the other hand, in some places, it is literally on the 7th floor! In a few places, the underground church is the only Catholic church in the area. In still other places, people meet for Mass or prayer in people's homes. These are the communities most vulnerable to the surveillance of the Public Security Bureau. In some open seminaries, underground bishops serve as professors. In a few places, both the open and the unregistered church share the same building for services while in other places the two groups are at complete loggerheads. Still in other places, a man may be a bishop in the underground church and a priest in the open church.”15

There are CPCA bishops appointed by the Beijing authorities who are not approved by Rome, bishops appointed by Rome who are not accepted by Beijing, and a much larger group of CPCA bishops (and priests) who have the sanction of both Rome and Beijing. The number of Patriotic bishops not in communion with Rome is said to be small.16 Rome has excommunicated CPCA bishops as recently as 2011, but the Vatican has never declared Patriotic Association Catholics as schismatic. The Holy Spirit Study Centre of the Diocese of Hong Kong provides statistics that acknowledge separately both “open Church” and “underground” clergy and churches in China, but points out that the Diocese of Hong Kong accepts baptismal, marriage and confirmation certificates from CPCA churches. The Centre encourages Catholics visiting China to attend Mass from CPCA churches rather than try to find “underground” communities.17

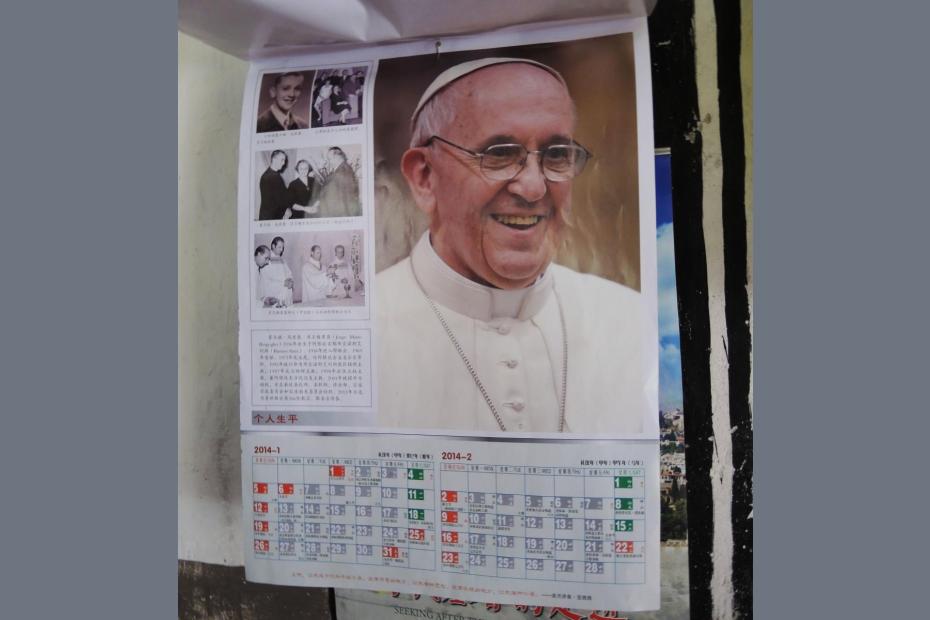

While the CPCA supposedly has no ties or loyalty to the papacy, the influences and connections between them are manifold and quite apparent to a casual observer. Prayers for the pope are often included in CPCA Masses, which are celebrated according to the Pauline (i.e. post-Vatican II) rite. The Roman catechism is a primary source for ordinary catechesis. Other connections are symbolic, but obviously important. The new CPCA cathedral in Kunming, for example, is movie-set Roman in its design. In many CPCA churches, one can often see pictures of Pope Francis.

There are Chinese Catholics who suffered severely for loyalty to Rome, whose discontent in light of that prevents them and others on principle from joining the CPCA, but so too is it true that almost all CPCA members before 1976 suffered persecution as well. In the past, there have been many examples of conflict between communities, leaders, and believers who joined the CPCA and those who would not. Still, those familiar with the situation today suggest that it would be misguided to construe the underground church today as a force equivalent to Poland’s Solidarity. More commonly, the unregistered church is said to comprise believers who celebrate at house Masses and simply hope not to have church affairs fall under the rule of atheist government entities.

Richard Madsen argued in 2000 that the legacy of above-ground and underground churches is a leadership problem that has made Chinese Catholicism more fragmented and localized. “To an unprecedented degree, then, the nature of Chinese Christianity is now being determined by local communities drawing on the resources of local culture.”18 This is particularly manifest among the burgeoning home-grown Protestant churches in China, but Madsen also sees evidence for this localization in Catholic rural communities, in a variety of Marian apparitions and folk-Chinese Marian devotions.

Based on anecdotal accounts, it is clear that many Catholics in Patriotic churches see themselves as part of a transnational Catholic community. The coexistence and overlap of the Roman and Patriotic churches complicate any attempt to describe lay Catholic life in China on this website. Political sensitivity also makes it difficult to discuss such matters with ordinary Chinese. In light of this, while acknowledging the complications involved, Catholics & Cultures includes Patriotic church members on the site alongside “underground” or unregistered Catholics regardless of the status of their bishop, since even that is not always apparent. All the images of worship here are from CPCA-affiliated churches.

Cultural contexts

Though the political context for Chinese Catholic life is difficult to ignore, as it is in any country, the cultural and social context for Catholicism in China – the primary focus of Catholics & Cultures – bears attention.

Confucianism, with its emphasis on harmony, filial devotion, benevolence, ritual practice and propriety, and cultivation of poetry and the arts, set some of the ideals for Chinese society. The Jesuits who brought Catholicism to China recognized the importance of these values in Chinese society, and shaped Chinese Catholicism along these lines. Confucian values were radically destabilized during the Maoist years, but still have a place in contemporary society, and are values that the current government has worked hard to reinforce as most authentically Chinese.

Richard Madsen, a scholar of Chinese Catholicism, argues that Catholic belief in China has been much more influenced by folk-Buddhist religious belief than by Confucianism. Having been initially most successful in rural contexts among peoples who were outsiders in the eyes of the dominant Confucian culture, and having been led by lay people with little formal education through many periods in its history, he argues, “Chinese Catholics picked and chose parts of their tradition that made their beliefs similar in structure to those of heterodox folk-Buddhism.” Madsen points to the intensity and quality of Marian devotion, Marian-centered apocalyptic episodes in rural areas, emphasis on Marian-mediated salvation, and reports of “exorcism and healing rituals” in rural underground churches “that seem of dubious orthodoxy to educated Western Catholics.”19 Henrietta Harrison, on the other hand, ascribes such values also to historical events of the last several centuries connected to the colonial encounter between European missionaries and Chinese Catholics, and to events that threatened the existence of local Chinese Catholic communities.20 Shanghai scholar Rachel Xiaohong Zhu sees the rise of charismatic Catholic prayer groups in Hebei, beginning in the mid-1990s, as having an even more salient impact on Chinese Catholic culture in many provinces today.21

Madsen notes elsewhere, Chinese Catholics “talk about miracles a lot. Almost all the true-believing Catholics we asked said they had personally experienced miracles, and they often claimed that their faith was strong precisely because they had been blessed with such experiences. The most commonly cited miracles are humble acts of unexplained good fortune.”22

“As rural Chinese Catholics talk about it,” Madsen recounts, “salvation is decidedly other-worldly – a matter of going to heaven and avoiding hell. They talk a great deal – more than most Catholics in the West – about heaven and hell. As a 35-year-old Catholic man puts it, ‘Life is short, but heaven is forever.’ After death, they say confidently, those who have been baptized, have prayed regularly, and have received the sacraments will go to heaven, usually after a stint in the fires of purgatory. Bad people will go to hell… Although [good but non-believing] non-Catholics will not go to heaven, they say, the non-Catholics will not necessarily be claimed by the devil. They will go to limbo, which is not all that bad a place. Some of the Chinese Catholics with whom we spoke filled the empty doctrine of limbo with a rich Chinese folk-religious content.

“God, as most Catholic villagers imagine him, is a stern accountant. A 50-year-old woman describes what God will do to a sinner kneeling to face him. ‘God will never help him because he is full of sin. God knows his sins. God will note this in his account book. Such a person will not come to a good end after death.’ A Chinese Catholic seminarian now living in the United Sates finds it odd that American Catholics speak of Jesus as a ‘friend.’ ‘We think of Jesus not as a friend, but as a ruler.’”23

Having been shaped in the past overwhelmingly in rural contexts, Catholicism faces new challenges in a country that is now primarily urban, and increasingly wealthy.

The shift from village to urban life is a cultural change of enormous significance, though its long-term religious implications are still unclear. This is particularly salient for Chinese Catholicism, which was long grounded in rural pockets of the country in majority-Catholic villages.

Especially in the Eastern part of the country, China is modernizing and urbanizing at a breathtaking pace. To visit major Chinese cities is to be nearly overwhelmed at the pace and scale of construction and technological change. Old neighborhoods are displaced by new high-rises in short order. Public infrastructure is far better than in most of the industrialized West, and though average incomes are not as high as in the West, cities are becoming consumerist heavens for those with money to spend, though the ethos among middle class is still to save and invest, rather than consume.

Many writers note that urban China, in particular, is facing a kind of spiritual or moral vacuum in an era when Communist ideology rings hollow, but public deference to the Party is an absolute requirement.24 Endemic corruption and instances of adulterated food supplies and shoddy building by private companies have undermined public confidence, so much that President Xi Jinping has made it a major priority to root out corrupt officials, including both “tigers and flies.” Nationalism remains a powerful force, but amidst all the boom and prosperity, a good deal of thought goes on about how to find a suitable foundation for public morality. The Party has even tried rehabilitating Confucius as one source of national wisdom, though it has not repudiated Mao. In this cultural context, Catholicism is often “justified” as a way to find a basis for that morality, as primarily an ethical system validated by the good results it brings.

While at least half of the Chinese population claims affiliation with no religion, and a large proportion are atheist, it would be wrong to suggest that even urban Chinese live in an entirely “disenchanted” or de-mystified rationalist world. Belief in Feng Shui, numerology, luck and magic permeates all strata of Chinese society. Buildings are built to honor Feng Shui principles, and sell at a discount if the principles are violated. Marriage dates and other big events are chosen on the basis of their perceived auspiciousness. Funeral practices generally comply with folk-religious norms.

Read more

Rev. Jean Charbonnier, MEP, ed. Guide to the Catholic Church in China 2014 (Singapore: Oxford Graphic Printers, 2013).

Ian Johnson, The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After Mao (New York: Pantheon, 2017) focuses on Buddhism, Daoism and Protestantism, and provides an interesting context for the changes facing Catholicism in China.

Henrietta Harrison, The Missionary’s Curse and other Tales from a Catholic Village (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2013).

Richard Madsen, China’s Catholics: Tragedy and Hope in an Emerging Civil Society (Berkeley: University of California, 1998), though 20 years old, provides excellent descriptions and analysis of Catholic village life in Hebei province at that time, along with insights on rural Catholics who had moved to the cities.

Kin Sheung Chiaretto Yan, Evangelization in China: Challenges and Prospects (Maryknoll: Orbis, 2014) offers a concise history of Catholic presence in China and focuses primarily on opportunities the author sees for Catholic evangelization in China.

Fenggang Yang, Religion in China: Survival and Revival Under Communist Rule (Oxford University Press, 2012) provides a helpful overview on the broader situation since 1978, and posits ways that Catholic black and gray "markets" for practice have impacted life there.

- 1One prominent scholar, Fengang Yang, has suggested that within a generation China will be home to more Christians than any other country in the world. See Tom Philips, “China on course to become 'world's most Christian nation' within 15 years” The Telegraph, April 19 2014. In light of the sheer size of the population, that seems possible, but one would also have to remember that it is home to the largest population of atheists as well. Rodney Stark and Xiuhua Wang go so far as to postulate “plausible” growth in the total number of Christians to 579.5 million by 2040. Rodney Stark and Xiuhua Wang, A Star in the East: The Rise of Christianity in China (West Conshohocken, PA: Templeton, 2015) 115.

- 2The Holy Spirit Study Centre of the Catholic Diocese of Hong Kong estimates as many as 12 million, including Catholics not registered with the government, and therefore not counted in CPCA figures. In the recent issue of its newsletter, Tripod (vol. 35, no 176), published in Chinese, the Center estimates 10.5 million as of December 2014.

- 3For a fuller discussion of the variety of estimates of the size of the Catholic population in China, see Kin Sheung Chiaretto Yan, Evangelization in China: Challenges and Prospects (Maryknoll: Orbis, 2014) 40-44, 56. Yan estimates that Catholics today constitute about the same percentage of the total population as in 1949. He puts the total percentage of the population as somewhere between 0.4 percent and less than 1 percent.

- 4 One estimate suggests that in 1949 Catholics outnumbered Protestants 3 to 1, whereas today, Protestants probably outnumber Catholics 4 to 1. Yan, Evangelization in China, 42.

- 5All three were occurring at the same time in August 2015, during which time one could see a major renovation of a Catholic church in Jiaxing, construction on a huge church in Kunming, and crosses being removed and unapproved church buildings being demolished under the “Three Rectifications and One Demolition” campaign. On episcopal appointments, see http://www.scmp.com/news/china/policies-politics/article/1848561/china-preparing-ordain-second-bishop-amid-signs-thaw.

- 6Richard Madsen, “Chinese Christianity: Indigenization and Conflict” in Chinese Society: Change, Conflict and Resistance, ed. Elizabeth J. Perry and Mark Selden, 2nd ed. (New York and London: Routledge Curzon, 2003) 273.

- 7Cindy Yik-yi Chu, “China and the Vatican, 1979-Present” in Catholicism in China, 1900-Present: The Development of the Chinese Church, ed. Cindy Yik-yi Chu (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2014) 150.

- 8To take but one example, a priest in the Lancang Valley reported that despite problems of drug abuse in many nearby communities, Catholic families had not struggled with this problem. He bragged that the prefecture police chief, though not a Catholic, had commented on how much easier his job would be if all the families in the region were Catholic. Other villagers likewise pointed out that Catholicism was a strong foundation for public morality.

- 9At the peak of this missionary era there were probably just over 200,000 Catholics in China. The literature on early Jesuit engagement is extraordinarily rich--much richer and more nuanced than the literature about contemporary Catholic life in China--and too long to list here. For the best account of the era, including an account of how important Chinese believers were in spreading the faith, see Liam Matthew Brockey, Journey to the East: The Jesuit Mission to China, 1579-1724 (Cambridge: Harvard Belknap, 2008). For a shorter account, one might turn to John Witek, SJ, "Christianity and China: Universal Teaching from the West," in Stephen Uhalley, Jr. and Xiaoxin Wu, eds., China and Christianity: Burdened Past, Hopeful Future (Armonk and London: M.E. Sharpe, 2001), 12-27.

- 10In Shanxi province, where there was a large Catholic community, more than 6,000 Christians were killed and many churches and church buildings were destroyed in the Boxer Rebellion in 1900. See Henrietta Harrison, The Missionary’s Curse and Other Tales from a Catholic Village (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2013) pp. 92-115. In Yunnan’s Lancang River Valley, Yellow sect Buddhists killed missionaries and converts and burned churches in 1905. In both cases, indemnities were extracted that helped build even larger churches and built up new communities.

- 11In The Missionary’s Curse and Other Tales from a Catholic Village (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2013), Harrison offers a first rate account of the ways that 19th-century missionaries colonial attachments left a complex and explicit legacy in Catholic villages in Shanxi Province.

- 12Until March 2018, the State Administration for Religious Affairs was the entity formally responsible for monitoring the Church’s activity, and the CPCA was a mechanism for that work. Subsequently, the United Front Work Department assumed the SARA's role. The implications of this are unclear, though many fear that it means closer government control of religious institutions and practice.

- 13Henrietta Harrison, The Missionary’s Curse and other Tales from a Catholic Village (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2013) 145-175, 182; Richard Madsen, China’s Catholics: Tragedy and Hope in an Emerging Civil Society (Berkeley: University of California, 1998) 50-75.

- 14In an article about possibilities for resolving the challenges of the church in China, Hong Kong's John Cardinal Tong used the terms "unofficial" and "official" to describe the two churches. "The Future of the Sino-Vatican Dialogue from an Ecclesiological Point of View," Sunday Examiner (Hong Kong) Feb. 11, 2017.

- 15Betty Ann Maheu, "The Catholic Church in China." America 7 Nov. 2005: 8. This perspective contrasts with the observation of Richard Madsen who saw, in the 1990s, much more conflict between CPCA and underground church leaders, also manifest among many believers. Richard Madsen, China’s Catholics: Tragedy and Hope in an Emerging Civil Society (Berkeley: University of California, 1998) 60-125.

- 16For more in-depth discussions on the complexities of Sino-Vatican relations and episcopal appointments, see Cindy Yik-yi Chu, “China and the Vatican, 1979-Present” and Jean-Paul Wiest, “Sino-Vatican Relations under Pope Benedict XVI” in Catholicism in China, 1900-Present, ed. Cindy Yik-yi Chu (New York: Palgrave McMillan, 2014).

- 17Holy Spirit Study Centre of the Diocese of Hong Kong, Information http://www.hsstudyc.org.hk/en/china/en_cinfo_faq.html (last accessed November 6, 2015)

- 18Richard Madsen, “Chinese Christianity: Indigenization and Conflict” 275-278. One Chinese interviewee in Ian Johnson's The Souls of China ascribes much of contemporary Chinese religious entrepreneurialism to a different cause: "People can't believe ho corrupt society has become... In the past, it was just businesspeople and government officials who were corrupt. Now it's monks, priests, pastors. So what's your reaction? Found your own church, your own home Daoist temple, you own study group of the classics. Do it yourself." Ian Johnson, The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After Mao (New York: Pantheon, 2017) p. 295.

- 19Richard Madsen, “Beyond Orthodoxy: Catholicism as Chinese Folk Religion” in Stephen Uhalley, Jr. and Xiaoxin Wu, eds., China and Christianity: Burdened Past, Hopeful Future (Armonk and London: M.E. Sharpe, 2001) 233-249.

- 20 Henrietta Harrison, The Missionary’s Curse and Other Tales from a Catholic Village.

- 21Rachel Xiaohong Zhu, “The Catholic Charismatic Renewal in Mainland China,” Review of Religion in Chinese Society 1 (2014) 173-194.

- 22Richard Madsen, China’s Catholics: Tragedy and Hope in an Emerging Civil Society (Berkeley: University of California, 1998) 94.

- 23Richard Madsen, China’s Catholics: Tragedy and Hope in an Emerging Civil Society (Berkeley: University of California, 1998) 86-87.

- 24In his recent prize-winning book, Age of Ambition: Chasing Fortune, Truth and Faith in the New China (New York: Farrar, Strauss, 2014), Evan Osnos devotes a good deal of attention to what he perceives as a “spiritual void.”