Though commonly referred to simply as bailes, the dance groups are really lay religious confraternities — sociedades religiosas — organized to express their devotion through dance. Typically about half of the members, called promesantes, are actually dancers.1 Others, socios, help primarily with organization, fundraising, setup, chores, evangelization and accompaniment of young people.

Members often say that the bailes are a way of life, not just an organization. Many use the term “family” to describe their bond, and indeed, bailes are often made up primarily by a small number of extended families. Many of the dancers reported having grown up wearing a traje, the sacred costume, in the dance since they could first walk. Not as many people join as adults, except through marriage, but the willingness to welcome others into the group seems strong. Two gay men reported having joined in recent years and having been, despite their worries, welcomed by different groups. One, who had been introduced to the dances by his husband, said, “I had a feeling, a spiritual sensation that I had not felt in a long time. I found a family here that I had not felt in a long time.” Experienced members even serve in a quasi-familial relation, as padrinos or madrinas, godfathers and godmothers, to new members.

As a form of prayer, the dance is communal. Dancers establish a direct relationship to the Virgin, but always do so with their family. Dancers, as pray-ers, follow the cues of others, particularly their leader. The individual and the group gather before the Virgin in such a fashion that neither diminishes the other. Those with the most experience dancing get to be closest to her, in the front. The younger dancers are taught to gradually move closer to her.

At the same time, rules for the bailes are fairly clear and formalized. The success of an event as big as La Tirana — some 200,000 people in a town of about 1,000 year-round inhabitants — requires a remarkable degree of coordination, most of which is handled by a formally structured federation and associations that work under its wing. Dance schedules need to be coordinated, routes cleared, and liturgies arranged with the clergy. In what is said to be the driest desert in the world, water has to be trucked in and delivered, and sanitation has to be accommodated, particularly in the vast areas of desert that have been given over for tents for bailes at the outskirts of town. Parking lots have to be attended and traffic diverted at gates. The fire department requires volunteers. From the perspective of many dancers, too, there also needs to be coordination of the moral order of things — to prioritize catechesis and evangelization; to ensure that the celebration remains religious in nature, not devolving, as carnival did, into a secular feast; and to ensure that particular traditions embodied in older dance groups are not lost. A federation and the associations that fall under it ensure all these things.

On the level of each baile, as well, participation requires considerable organization to raise funds, to manage owned or leased property in La Tirana, to arrange transport and to enable common life for groups of 50 or more people at the feast. Dues can range from about US$14 a month for children to US$40 for adults. One group described a nearly year-round effort to raise the rest — with bingos and chicken dinner fundraisers in the neighborhood, when every dancer must sell a certain number of tickets. The largest portion of these funds goes to paying a band. “The cheapest band here costs 1.5 to 2 million pesos [US$2,200 - $3,000],” one leader reported. Several groups said their band cost twice that, and the largest groups, they claimed, paid as much as 12 million pesos. Aside from the band fees, they have to pay to transport and feed everyone.

Since 1965, La Tirana’s feast has been governed by the Federation of Religious Dance Groups of Iquique, a lay public association formally recognized by the Church (La Tirana falls within the Diocese of Iquique) in 1978 as a juridic person under the approval of the bishop.2 The diocese approves its charter, and members say that they have broad latitude to govern themselves. Its leaders are elected lay people from the recognized bailes.

The federation recognizes 11 associations as eligible to send members to dance at La Tirana. Many of the associations predate the federation, but all accept the federation, which they created, as their overriding authority for jurisdiction over the bailes that dance at La Tirana. Each association is responsible for a group of bailes in a single urban area. In the city of Arica, where the bailes interviewed for this study come from, there are two associations that dance at La Tirana, the Association Virgin de la La Tirana (f. 1962) and the Association San José (f. 1972).

It bears noting that the La Tirana federation is only concerned with the bailes who dance at La Tirana. In Arica, for example, there are actually 114 bailes, only 40 of which dance at La Tirana. Others dance at feasts such as San Lorenzo de Tarapaca, Las Peñas, Timalchaca, and Arica’s Fiesta de la Pascua de los Negros, which marks Epiphany.

Each baile is legally incorporated, and notes the date of its foundation on an elegant cloth standard that it carries with them. As a corporation, it raises funds and owns or leases the property where it lives during the feast. A baile’s primary leaders are its president and caporal. Like all the group’s leaders, they are lay people elected from among the members, for terms lasting three years. The president organizes daily life, finances and preparations of the socios. The caporal rehearses the group weekly from March onward; leads the dance, usually from its center; and is supposed to see to the spiritual formation of the dancers. His or her symbol of authority is often a whistle or a matraca (a wooden grinder instrument) used to signal a change of dance or song.3 Though only men danced in the bailes generations ago, women and men serve as presidents and caporales, and many groups identify a woman as their founder. More dancers tend to be women; almost all musicians tend to be men. Older interviewees said that caporales used to be very strict, but today, while they are still responsible for discipline, they are more like affectionate friends and encouragers, though they enforce discipline as they have to, if an action would cause harm or embarrassment to the baile.

Each association is supposed to be assigned an asesor, a priest who works with the lay leaders to ensure spiritual formation, presides at special liturgies, coordinates retreats during the year, and is present at special events like anniversaries. As both dancers and asesors described it, the asesor clearly holds a place of significant respect in the bailes and associations, but has only an advisory voice in matters of governance, and is often outvoted, particularly on matters like discipline, where they tend to be more lenient. As one caporal summarized it, “The priest gets to suggest, but it is always a vote of the associations.” The rector of the sanctuary of the Virgen del Carmen also has a significant role as leader, along with the bishop and many other clergy, of the liturgical aspects of the feast.

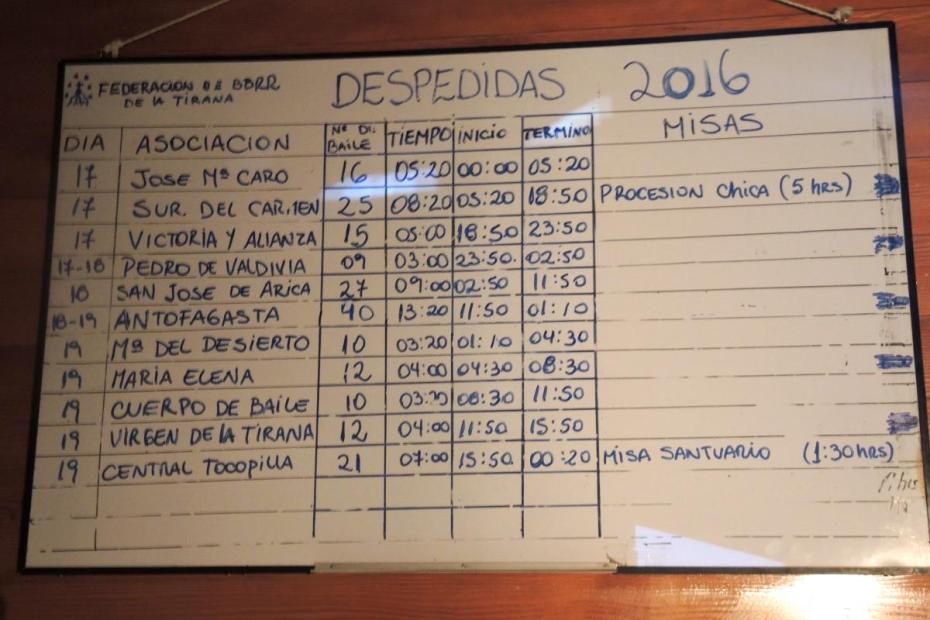

The federation sets out the broadest rules. The associations their bailes may set rules that do not contravene the rule of the federation. The federation is often involved when bailes want to make some change to “update” their dance or trajes or music. Moving 197 bailes into the temple and out also requires coordination. For the very important arrival and farewell dances in the sanctuary, the federation assigns time slots to each association, and the association in turn decides the order that its bailes get to dance. That order is determined by the degree to which the baile has adhered to the expectations for Mass attendance, retreat attendance, spiritual formation, dues payment and volunteerism for the many tasks that need doing in town and at the sanctuary during the feast. All of this is calculated using a point system. For example, if a group exceeds the 20 minutes it is allotted to go before the Virgin in the temple, it loses many points. The bailes that achieve the most points dance first, the rest in descending order. All of those determinations are made by lay people.

One priest who spent years as asesor to the bailes indicated that he thought that the organizational forms, and the adherence to structure, was an outcome of union organizing structures and work life in the nitrite mines where the dancers were rooted in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.4

Though there were no overt signs of tension, dancers, not surprisingly, have a variety of perspectives on the best governance of the feast. Some interviewees hinted that the rules set by the federation are at times too inflexible — power exercised for its own sake — but older interviewees who remember the lack of order before the federation was formed, see it differently. One recalled a time when bailes arrived by truck and raced to the shrine, jostling in “undignified” ways for position to go before the Virgin. Defenders of the structure say that it has been successful in preserving particular traditions that might otherwise get lost too easily, and preventing it from devolving into secular carnival. The federation even managed to prevent alcohol sales in town during the feast to ensure better order. Overall, the larger values of the federation were echoed repeatedly by dancers interviewed there. The rules are “strict,” one noted, but conceded that they are necessary “because making a change would involve losing a tradition.” The fear of losing a tradition, even one assembled piecemeal over the last century, as many are quite aware it was, is an important driver for the dancers and other promesantes there.

The growth of the number of bailes which necessitates a waiting list for bailes hoping to dance at La Tirana in July,5 certainly acts to reinforce its authority, since running afoul of the rules can mean that a group’s space there is turned over to a new group.

Ritual, membership and belonging

Membership for dancers in the bailes is ritualized before the formal dances by putting on some part of the traje, or dance costume. Taking it off at a last dance at the completion of a manda after which a dancer does not expect to dance again, often stirs tears. Like the habits traditionally work by members of religious orders, it symbolizes not only a special relationship to the Virgin, but also to the group.

Members form very deep bonds to their own bailes, often lasting a lifetime. Bailes often commemorate their deceased members at La Tirana, and during the year members attend funerals even for those in their broader association. Many interviewees talked about how the bailes become a significant part of their social world. They go to the beach together in summer, raise funds at bingos or food sales. Switching membership between bailes is powerfully discouraged by shared norms. Even some married couples reported that each danced in a different baile while at La Tirana, though their children had the right to choose whichever baile they preferred.

For all the community that develops, bailes are not simply social organizations that happen to dance. Devotion to the Virgin is clear and palpable among the great majority of dancers interviewed, and dancing to her is a driving reason to be there. It requires huge sacrifice. Interviewees often noted that the groups were a good way to keep children on a straight path, but seldom seemed to think instrumentally about this. They went, they said, to express devotion to the Virgin; the fact that their kids stayed out of trouble was an outcome of the membership, but not the purpose of it. As is true for the dancers, most of the lay people who volunteer at La Tirana do so to fulfill a manda, a promise to carry out certain acts for a deliberate period of time, generally in supplication for something in particular, or in thanks for receiving it. Mandas tighten devotees’ relationships to the Virgin in evidently powerful ways. All interviewees spoke of mundane reasons why people joined the dance, such as when a boy joins a baile because he is interested in a girl who dances in it, but suggested that this was an acceptable starting point, a way of drawing people in, presuming that the young man was also loyal to the spirit and rules of the group.

If there were any sign of what dancing means to those who do so, it may be this. The worst penalty that a baile or association could give for an infraction is that a dancer might not be able to dance for some period of time.

Read More

For a fuller summary of the organizational structure of the bailes, see José Javier García Arribas, Los Bailes Religiosos del Norte de Chile o los Danzantes de la Virgen (Santiago: Seminario Pontificio Mayor, 1989) 162-186.

- 1The term promesantes refers to the promises one makes to the Virgin as the primary requisite of membership; socios means partners.

- 2José Javier García Arribas, Los Bailes Religiosos del Norte de Chile o los Danzantes de la Virgen (Santiago: Seminario Pontificio Mayor, 1989) 162.

- 3Matracas are also used by all dancers in morenos dances, but only to keep time. A caporal can wield them differently than regular dancers can.

- 4Personal interview with Rev. Eugenio Barber, S.J., Santiago, Chile, March 2, 2014.

- 5As many as 30 groups are said to be in line for this. These groups have the opportunity dance at a special, shorter feast in la Tirana in September.