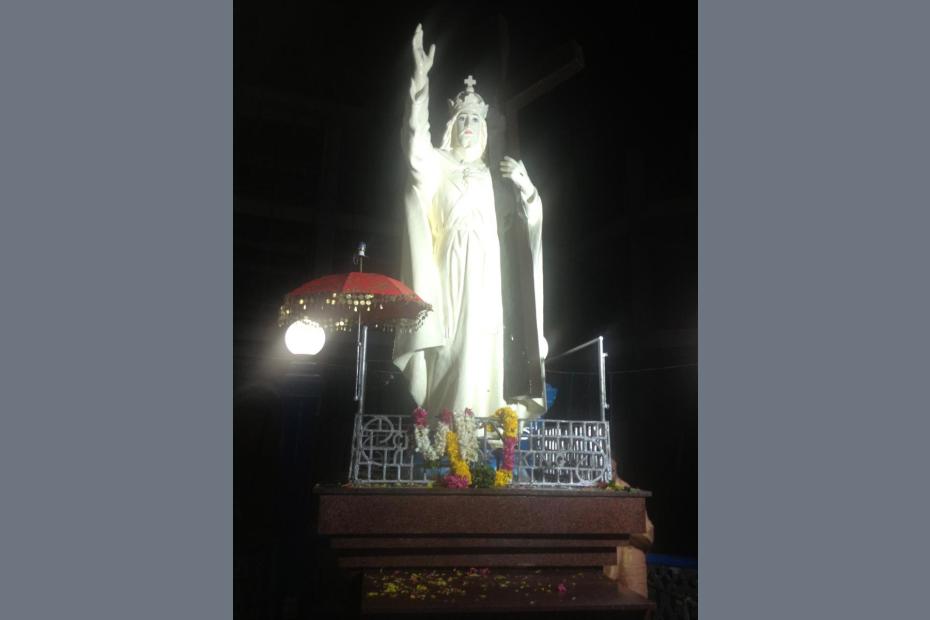

Shrines play an unusually big role in Catholic life in southern India. Almost all Catholic churches there have shrines in front and inside. Towns with a significant Catholic population often feature a Catholic shrine near the center of town or at a crossroads, and there are many unofficial shrines built and maintained by individual families or groups of families. Pilgrimages and shrines in India are not simply a populist phenomenon, something elites might avoid.1 Worshipers stop by them steadily throughout the day, offering brief prayers, and signaling that these are active places of religious power, not simply relics from the past. Pilgrims make special trips to the more important of these sites and consider those pilgrimages as important occasions in their lives.

Large shrines in Velankanni, Bengaluru, at St. Alphonsa's tomb at Bharananganam, and St. John de Britto church in Tamil Nadu, are among the prominent pilgrimage sites. The St. Mary's Forane, or Kuravilangad Church, in Kottayam, a Syro-Malabar church and shrine, draws its legitimacy from a reputed appearance of the Virgin at a spring in 105 AD.

India's landscape is so replete with shrines and holy sites, some drawing massive crowds, others only local devotion, Diana Eck writes, that "there are so many tīrthas in the sacred geography of India that the whole notion of "sacred space"as somehow set aside from the profane is cast into question. In Hindu India, sacred space is so vastly multiplied that there is little untouched by the presence of the sacred."2 These spaces, she writes, are created not only by priests and sacred literature, but also "by the countless millions of pilgrims who have generated a powerful sense of the land, location and belonging through journeys to their hearts' destinations."3

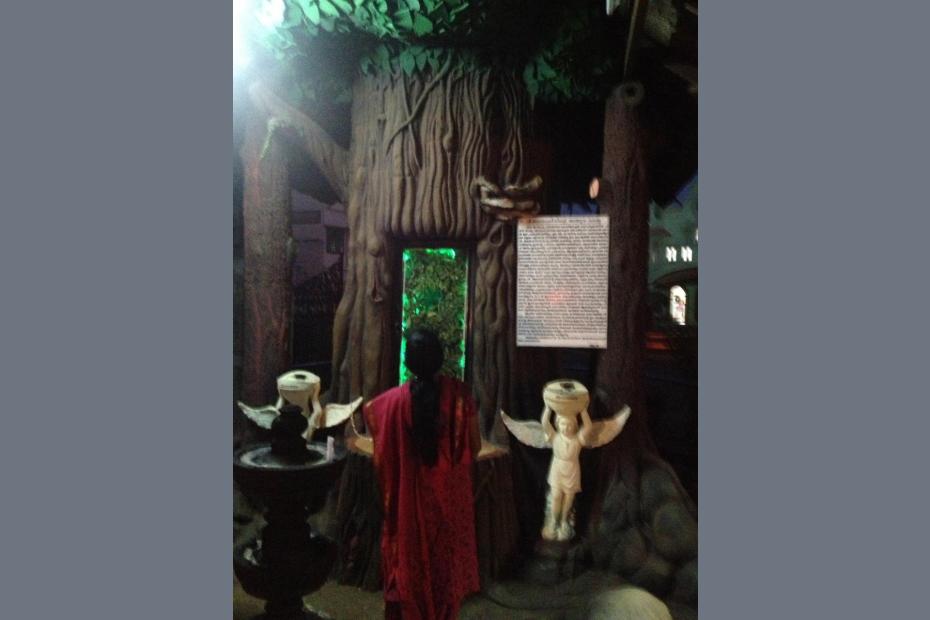

Catholic shrines "overlap" the Hindu sacred landscape, rather than simply replacing the latter. The Catholic shrines in souther India draw legitimacy from parallel streams in Hindu and Western religion, both of which shaped Indian Catholicism. Therefore devotees at Catholic shrines in some places are often as likely to be Hindu "Christ bhaktas" - Jesus devotees - as Catholics. An audio interview with Ganesh, a Hindu man visiting St. Mary’s Shrine in Bengaluru, exemplifies that trend. Shrines expect that many visitors will be Hindu. They, like Catholics, go to the shrines to pay their respect to potentially miraculous intercessors, to make a promise in return for some favor, or to fulfill a promise made. As Eck describes them, Hindu holy sites and the stories behind them frequently narrate some divine act of creation that yielded a particular river or coastland other geographical feature.4 Catholic sites, interestingly, do not seem to make claims about creation in India, but about divine irruption into an already created world.

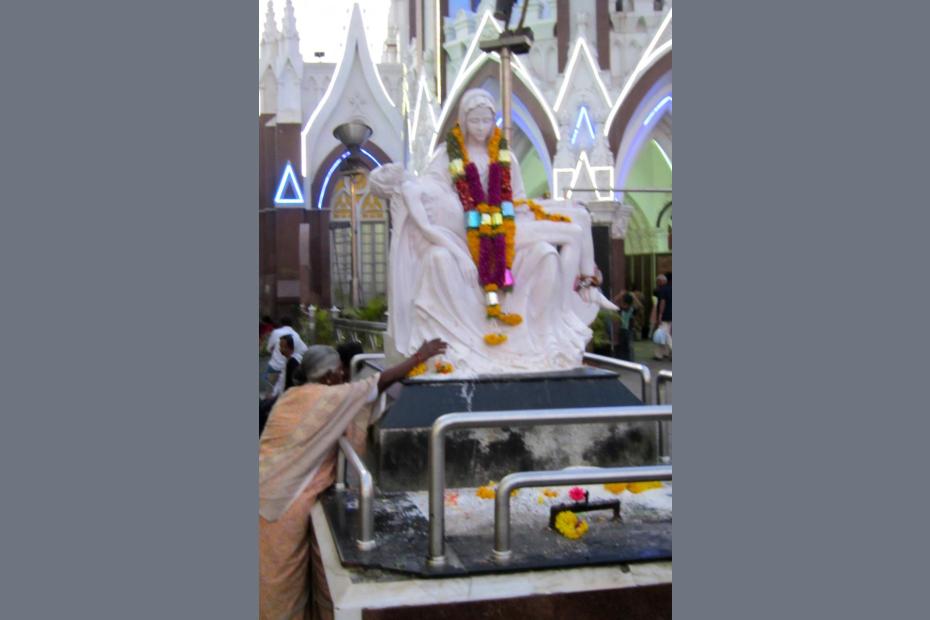

Sight (Darśan) and touch (Pranāma) are as important in Indian Catholicism as they are in Hinduism. Believers regard it as especially important to behold a saint or holy person in some physical way, so as to put the saint and the believer in sight of one another. Touch is similarly essential, as a mark of respect, of physical connection, and as a way of developing mutual affection. Pranāma is the Hindu practice of touching the feet of a saint as sign of devotion or respect. Catholic worshipers are also constantly seen touching the feet of religious statues. Sight and touch are regarded as providing a real and tangible connection to a saint, and are particularly prized to a degree that is not true in most of the West.

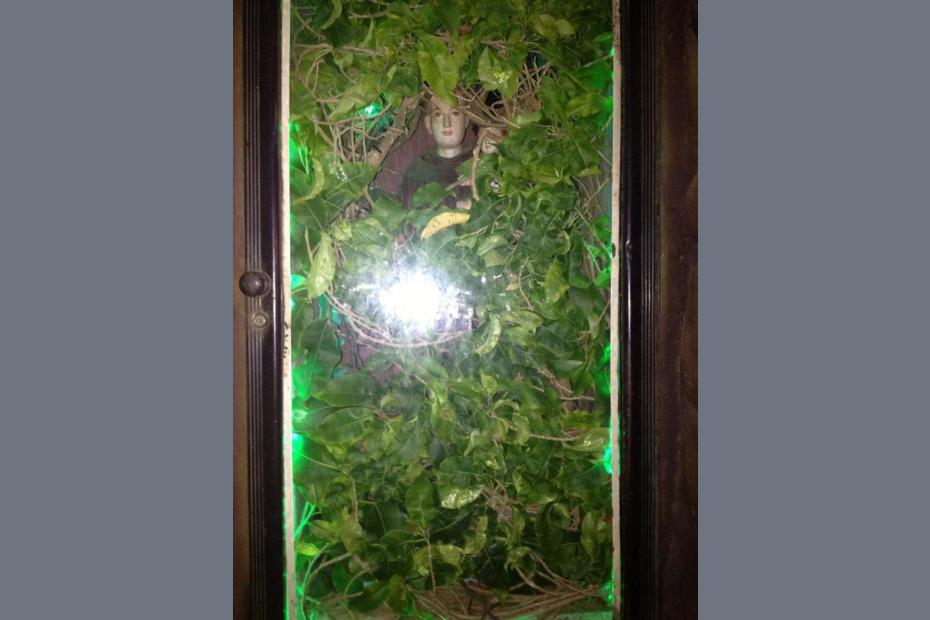

Interestingly, a number of churches have been putting saints behind glass, protecting them from the touch of the faithful and from dirtiness. In those instances, people are usually seen praying with their hands on the glass. Where there are signs that say "please do not touch the statues,” they are ignored, for reasons of devotion.

Prasadam

At the base of statues, whether in Hindu temples or Catholic ones, one almost always finds small plates or piles of salt, peppercorns, coconut pieces or other sweets.

These prasadam, as they are known in Hindu tradition, are foods offered to, and thus sanctified by the deity. Devotees generally bring these small offerings, leaving them for other devotees to receive. When received, they are regarded as sanctified gifts from the venerated saint himself, and a sign of blessing.

Exchange, prosperity and blessing

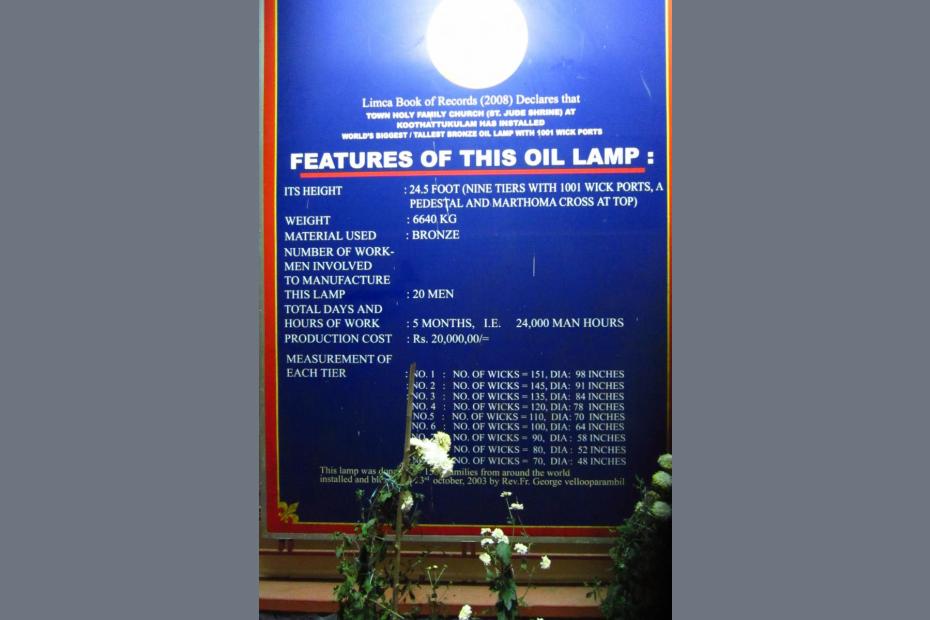

To a degree that would surprise many westerners, prayer often seems to be regarded as a way of moving God to grant blessing, or a form of mutual exchange. The shrine of the Miraculous Infant Jesus makes this connection especially apparent in a Christian context.

Listen to segments of an interview with Lukose, a civil servant in Bangalore, who describes the importance of physical images for worshipers in India, and the connection between worship and ethics.